What a 9-year-old saw in Teddy Roosevelt

His success crystallized my aspirations. If I could only be like Teddy, how sweet life would be.

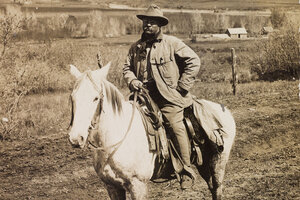

President Theodore Roosevelt returns to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, in 1905.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

I was rather disappointed when the 100th anniversary of Theodore Roosevelt’s death, on Jan. 6, was given little if any notice by the media. In the panoply of presidents, he is traditionally cited as one of the greats. This was something I was aware of from an early age.

Yes, I was an unusual kid. By the time I was 9, I had a favorite president. It might have been that trip to the American Museum of Natural History in New York where I first saw T.R.’s big-game trophies. Or maybe that image of him I ran across in a book, in buckskins with his arms crossed over his chest, ready to take on the world. Or maybe it was my mother who planted the seed, telling me what a sickly child Theodore had been, and how he had committed himself to developing both body and mind through his pursuit of the “strenuous life.”

Washington and Lincoln aside, the other early U.S. presidents seemed rather stuffy to me when compared to T.R. Their images were sepia toned and hung in oval frames lining the walls of the nation’s grammar schools. Before Roosevelt’s time, few people even knew what their president looked like. Teddy, by contrast, was America’s first “public” chief executive, thanks in great part to his gift for self-promotion.

In one of her reminiscences, his daughter Alice remarked that her father “always wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening.” He was the center of attention by his own design, and I didn’t want him any other way. Astride a leaping stallion, charging up San Juan Hill, or pounding his fist as he addressed adoring audiences, T.R. bespoke energy, if nothing else. He once wrote, “I have only a second rate brain, but I think I have a capacity for action.”

It was an odd thing to say, considering that Roosevelt wrote more than 30 volumes and was a voracious reader who read a book a day, even as president. He consumed a tremendous spectrum of literature, from poetry to classics to natural history. He also spoke French and could read Greek and Latin.

Now it comes back to me – the real why of Theodore Roosevelt in my young life. I was a skinny kid. I was bullied. I loved nature and books. I wanted to learn foreign languages. T.R. was my president because his success crystallized my aspirations. If I could only be like Teddy, how sweet life would be.

I realize that in speaking as the 9-year-old I was, I run the risk of hagiography, of idealizing a man who was, in fact, a very nuanced personality. As an adult I now see that T.R. was more complicated, and flawed, than I could have grasped as a child. Yes, he championed the common man, but he also harbored racial views that were matter-of-fact in his time but would meet with disfavor today. And in a world yearning for peace on many fronts, his bellicose streak might be more divisive today than it was in an earlier America just beginning to flex its muscles.

Still, for a city kid from New Jersey Roosevelt represented adventure, wide-open spaces, and irrepressible energy and optimism. Over time, as I grew, I may have had inklings of his personal shortcomings, but they were subsumed by the robust, forward-looking, bully man I always perceived Teddy to be.

By the time I got to college I was studying the classics, as T.R. had. I recall reading Pericles, the Greek general, who in his famous funeral oration said something I find particularly valuable in our age, which sometimes seems so sparing of the virtue of forgiveness: “His merits as a citizen outweighed his demerits as an individual.”

I think the old Rough Rider would have called that fair enough.