Kindness linked us on the Mongolian steppe

Father and son round up straggling sheep on an early spring morning in central Mongolia. The family also kept goats and yaks.

Lucy Page

I didn’t know quite what I was looking for when I flew to Mongolia for a semester abroad. I just needed something different, far from the late-night libraries of my college town. Most different, I hoped, would be my rural homestay: two weeks in central Mongolia with a family of nomadic herders.

My host family’s ger, a round white tent that Mongolians have carried across the steppe for centuries, nestled against the base of a rock outcropping. From the top of the rocks the steppe rolled to the horizon, a vast sheet striped with windblown snow. It was late March.

Each morning, my host mom cinched the sash of my Mongolian robe snug around my waist. Then I’d trail behind her, calling “shoo, shoo, shoo” to guide our yaks over moss-covered boulders. We’d smash rocks through ice to draw water from a nearby stream and collect dried dung in nylon sacks for fuel.

Why We Wrote This

On a homestay with a family of nomadic herders, our essayist discovers that, when shared language is limited, caring and kindness communicate more deeply.

In the evenings, we clustered in the warmth of the ger. It was just tall enough for me to stand up in, with two beds crowding an iron stove in the center, a set of shelves holding bent silverware and faded dishcloths, and a painted altar where photos of my host grandparents were propped next to Buddhist icons. We’d squeeze onto wooden footstools around the altar to play cards or watch Mongolian music videos on the solar-powered TV, while my host mom diced mutton for dumplings. I’d lose at Connect Four to my host brothers, Dalai and Dawaana, and make faces at my host sister, Lhamsuren, who straddled my lap and kneaded my cheeks like dough.

I was studying Mongolian at the time, but still, there was so much I couldn’t say or understand. We relied instead on short phrases and eager charades. As we tramped through snow behind the goats, my host mom, Tuvshintogoh, would ask me if I was cold, then giggle and pantomime a big shiver to make sure I understood. In the evenings, she showed me how to fold dumplings with exaggerated pinches and twists of her fingers. My host siblings would chatter at me, speaking too fast for me to understand, as we explored the boulders around our ger; I’d listen and nod and then, suddenly, swing them off their feet by the armpits.

This verbal obstacle was oddly freeing. In the crowded dining hall at home, meeting new people made me anxious. I’d stay quiet, measuring out my words, scrambling for something to say that wouldn’t expose me as unfunny, weird, boring. In Mongolia, I couldn’t fine-tune my words. I could only smile, hold Lhamsuren’s hand, and try out one of the phrases I’d mastered: “May I help?” “Where is the dog?” “Are you tired?” My host family guffawed at my pronunciation, at the way I threw up my hands and eyebrows in a frequent gesture of confusion. But in their laughter, I felt safe, unembarrassed.

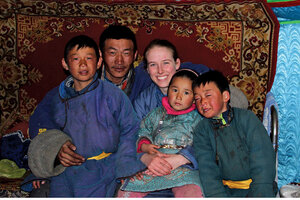

With my Mongolian family on the steppe, I found an ease I’d never felt before. The static in my head quieted. My fear of being judged – so long my nagging companion – began to wane.

We were so different, they and I, and not just in language. Their skin was hardened and darkened by sun; I’d been hidden under hats and sunscreen since birth. My host siblings grew up drawing water from frozen streams and jogging behind herds of sheep; I wiled away summers at tennis camp.

For me, these gaps made all the difference. Without shared social yardsticks, I wasted no time wondering how I was measuring up. Only real things – kindness, helpfulness – mattered. We were simply six humans, tiny against a vast Mongolian sky.