My Oregon Trail: Trekking from Boston with $200 and a bike

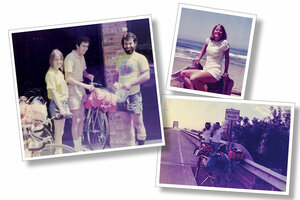

The author (left photo), Steve D., and Joe F. on Day Two. Joe and Steve at the Mississippi (bottom right). The author (top right) in her “goddess phase” at the Pacific Ocean.

Courtesy of Murr Brewster

“Visit, but don’t stay,” the governor of Oregon famously said in the ’70s, and when I arrived from Boston, I figured I’d made it in just under the wire. I didn’t know if I’d be accepted. But people were friendly.

“What brought you here?” they’d ask. Oh. I broke up with my boyfriend, nothing was tying me down, I wanted to shake up my life. All of this was true. That’s not what I said, though.

“A bicycle,” I said. Also true.

Why We Wrote This

The truly courageous part of doing something, our essayist finds, is to begin it. You cannot persevere if you talk yourself out of it. Once you’ve begun, you need only keep going.

People tend to be impressed if you’ve biked across the country. It did take effort, but I had some things going for me. Mainly, I already knew at least a dozen friends who had done it, although most had had the good sense to travel west to east, with the prevailing winds. I was not breaking new ground.

I had no expectation that I’d be backstopped or supported, or that it was even possible. Cash machines and cellphones did not exist, so we were accustomed to running out of money, and our loved ones were accustomed to not being in constant touch with us. We have so much to fall back on now that we’ve grown skittish of failure. We can’t even leave our houses without our phones, and we’ve lost sight of what is truly essential for survival.

OK, that’s just me being a curmudgeon.

In truth, I can’t say I was familiar with the essentials in 1976, either. But I set out with two men anyway, and with my entire savings: $200 cash. I also had a shiny new Mastercard – it had been only two years since women were allowed to have a credit card in their own name. None of us had trained for this trip in any way. We figured we’d get stronger every day, and we did.

We chafed in cotton shorts. We didn’t wear sunglasses or sunscreen. Or helmets. Our common sense didn’t take up much room. We had a small tent and a few changes of underwear, and we started pedaling on June 1, 1976. I assumed that if you just kept pedaling, the map would unfurl beneath your wheels until you eventually hit the next ocean over.

I didn’t worry about anything. That was my mom’s job. I called her collect from a phone booth with an update on where we were about four times over the course of the six-week trip. She was always glad to hear from me. I left out the more worrisome details, but none of them would stop us.

There were the unheeding coal trucks in Pennsylvania, the tornado warning in Iowa, the 115-degrees-Fahrenheit temperatures in Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, which we tried to traverse with a single water bottle each. We finally hitched a ride in a pickup truck. There were also the head winds that forced us to travel at night; we’d veer into the ditch whenever a car came up behind us.

By the time we reached the Pacific Ocean in mid-July, I was brown as a nut and had flossable quadriceps, but of course I was still bringing up the rear. The men had gotten stronger, too. We looked like Greek gods and, despite the myth we may have told our friends, we did not ditch our bikes in the drink at the trip’s end. I sold my orange Gitane for five bucks at a garage sale a few years later. I’m sure my friends’ bikes disappeared a lot earlier than that.

There were still donuts for sale, and I reassembled my former shape in record time.

Years back, people had the courage to step into a veritable bathtub of a boat and sail to an unknown land. They had the pluck to pile their belongings into a prairie schooner and keep going in case they stumbled onto a better deal. They had no way of knowing if they would see or hear from their loved ones again, and nothing was driving them but hope.

At least I had a Mastercard.

In my case, what looked like courage was probably just a mix of youthful ignorance and groundless optimism. I did learn something about perseverance, however. Most of it is about beginning. If you’re learning an instrument or a language, or if you’re starting your life over somewhere new, or taking on any kind of challenge, you won’t persevere if you talk yourself out of starting.

Once you get yourself in the saddle, you’re already more than halfway there. Then you just keep pedaling.