High-schoolers have made little progress since the 1970s, study says

Younger students have made some encouraging gains in math, but the lack of improvement among older students raises questions about recent education reforms.

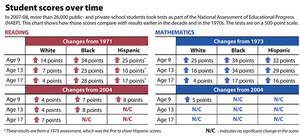

SOURCE: ‘The Nation’s Report Card: NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress’, US Department of Education/RICH CLABAUGH/STAFF

American 17-year-olds aren't performing any better in reading and math than their bell-bottom-clad counterparts in the early 1970s. That's one conclusion from the latest round of a national test tracking long-term educational trends.

On the positive side, the test shows that younger students – 9- and 13-year-olds – are making significant gains. In addition, racial differences in scores have narrowed for all three age groups over the past 30-plus years.

But overall, the mixed results parallel other indicators of how challenging it is to raise academic achievement.

The flat-line trend for 17-year-olds should sound an alarm, say advocates of high school reform. "If high schools were cellphones, they'd be considered in a dead zone," says Bob Wise, president of the Alliance for Excellent Education, a Washington advocacy group. "We've got to finally start addressing high schools in the same way that we addressed elementary schools.... This is the jumping-off place for college or the modern workplace, and our kids unfortunately are performing at [1970s] levels."

More than 26,000 students took the tests for the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) – a project overseen by the research wing of the US Department of Education. The results were released Tuesday. As part of the NAEP project, reading scores have been tracked since 1971 and math since 1973.

In the new report, long-term improvements were largest for younger age groups in math. Nine-year-olds gained 24 points since 1973, and 13-year-olds gained 15 points. In reading, the gains were 12 points and 4 points respectively since 1971. That's on a 500-point scale, which NAEP breaks into 50-point intervals to describe the corresponding skill level.

African-American and Hispanic students have improved at greater rates than white students since the 1970s, but since 2004, they've made little progress in narrowing these so-called achievement gaps. In 2008, for instance, the average reading score for white 9-year-olds was 228 – 24 points ahead of African-Americans and 21 points ahead of Hispanics.

The report card comes at a time when discussion is building in policy circles about whether there should be national education standards – or whether the multiple standards used by states under the No Child Left Behind law (NCLB) should be benchmarked to something common, such as NAEP.

"State tests are in many ways useless for making any kind of state-to-state comparison," says Frederick Hess, director of education-policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. "Whatever one thinks of national standards, it's imperative that we find a way to use NAEP as a backstop to let parents and voters know how to interpret state assessments."

NCLB critics point to various NAEP results since 2004 as an indicator of the policy's failure to bring about real improvements and close gaps. Some observers, however, look at the fact that the younger grades have made gains, and they say it's the outcome of a variety of policies, including NCLB, that have emphasized reading and math at those levels.

NAEP administrators caution against attributing good or bad results to any particular policy, given how many factors affect learning and how much school demographics have changed over the past few decades.

The stagnation of high school scores seems to draw the most concern with the new set of results. "It puts the lie to the idea [that if] you prepare them better in elementary school, they'll just move through the system and be better prepared high-schoolers," says Amy Wilkins, vice president for government affairs at The Education Trust, a Washington nonprofit. "We've got to get better high schools to get better high school outcomes."

The flat math scores among 17-year-olds happened despite the fact that larger percentages have taken higher-level math courses than in previous decades. That raises questions about whether such courses are really offering higher-level curriculum, whether the students bring the necessary math background to be successful, and whether the teaching is effective, Ms. Wilkins and others say.

In considering why 2008 NAEP reading gains weren't as strong as math gains, educational consultant Susan Pimentel says that most state standards have emphasized reading strategies but not high-level reading content.

"In talking to countless employers and postsecondary faculty from across the nation, they tell us they don't want students to just be able to summarize, analyze, identify, and locate [information in a text]; they want students to be able to [do so] in particular types of rigorous texts ... [such as] scientific journals, memos from employers, rich fiction, and biography," Ms. Pimentel said in a conference call with reporters Tuesday. She is a member of the National Assessment Governing Board, the independent bipartisan group that sets NAEP policy.

"Too few of our students are being challenged with rich, complex texts as we move up in the age groups," Pimentel added.

The new NAEP study is titled "The Nation's Report Card: NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress." This kind of NAEP test was last administered in 2004.

The results can't be directly compared with a separate set of NAEP tests, which take a snapshot of various subjects every few years and change over time with curriculum.