What's next for US spaceflight, if not the moon?

Under Obama's 2011 budget, NASA would cancel plans to put astronauts back on the moon by 2020 and hand off space-taxi services to private companies.

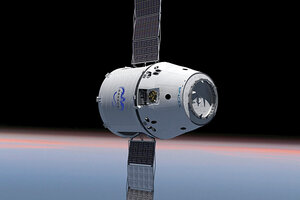

‘Dragonlab’: Artist’s conception of SpaceX’s reusable space ‘tug,’ designed to lift payloads to the space station.

SPACEX/AP

The Obama administration has submitted budget proposals to Congress that give a new direction to the US space program, particularly its human-spaceflight activities.

During the next five years, the president proposes to boost spending for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration by $6 billion over 2010 levels. However, gone is the ambitious Constellation program, which aimed to build a replacement for the space shuttle and put US astronauts back on the moon by 2020.

In its place – if Congress is willing (and several key lawmakers don’t appear to be) – is a NASA that would instead develop partnerships w ith the private sector. These would support the ability among commercial companies – from veterans such as Boeing to upstarts such as SpaceX – to build and operate rockets to provide cargo and taxi services to and from low-Earth-orbit destinations such as the International Space Station.

By handing off space-taxi services to private companies, administration officials say, NASA would be free to focus on developing technologies that would lead to far more powerful rockets and other capabilities to support human exploration of destinations that could include the moon, nearby asteroids, and, eventually, Mars.

The goal is to lay the groundwork for a truly national space transportation system, just as the government did nearly a century ago for aviation.

“Rather than setting destinations and timelines, we’re setting goals for capabilities that can take us further, faster, and more affordably into space,” said Lori Garver, NASA’s deputy administrator, during a budget briefing earlier this month.

What would NASA get in the proposed new budget?

President Obama seeks to spend $6 billion over five years for the transition to commercial launch providers. That would support higher-risk start-ups and help long-established rocketmakers – whose previous efforts have focused on launching satellites – to modify their rockets to meet NASA’s safety and reliability standards for human spaceflight.

At the same time, the budget contains nearly $11 billion over five years for developing technologies for a new generation of so-called “heavy lift” rockets – which can carry heavy payloads into orbit – as well as for developing and demonstrating technologies that would allow humans to move beyond low-Earth orbit.

It would also spend some $3 billion over five years to send robotic missions to potential destinations to act as scouts in advance of the arrival of astronauts.

What would be the biggest change for NASA?

The agency would be relieved of much of its remaining operational role in long-term human spaceflight. It would also increase its focus on pushing the technological frontier in ways that could help human explorers extend their range within the inner solar system.

“This brings NASA back to its roots as an engine of innovation,” said former astronaut Sally Ride during the budget proposal’s rollout.

Why were manned lunar missions canceled?

Money. The Constellation program never got the financial backing from the White House or Congress it needed to match the vision of returning to the moon by 2020. As a result, the program’s milestones kept slipping. Slippage translates into higher long-term costs.

Where would NASA fly in the future, and when?

Under the proposed budget plan, the International Space Station remains a destination through 2020 and perhaps beyond. Some suggest that the station could remain a viable research facility through 2025.

The moon remains on the destination list, along with asteroids, Mars, and gravitationally stable points where it’s possible to park a space station or perhaps a space-based refueling station.

But in the Obama administration’s budget, these become simply aspirational destinations, rather than trips on a schedule with deadlines attached.

That’s troubling to a number of the space program’s supporters. Many argue that it’s hard to set a clear course when you have no clear destination.

During a Feb. 3 hearing on NASA’s challenges, Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D) of Arizona, who heads the House Science Committee’s subcommittee on space and aeronautics, said she was disturbed by what she perceived as a lack of vision reflected in the NASA budget proposal:

“My concern today is not numbers on a ledger, but rather the fate of the American dream to reach for the stars,” she said.

What are the biggest challenges of a new course at NASA?

Perhaps the largest is “traction,” or long-term buy-in from Congress, as well as from NASA’s rank and file. That’s necessary to get the program going and to boost the approach’s prospects for outlasting any single president’s time in office.

The NASA track record for traction that spans several decades is uneven. After its start in 1961, the Apollo program failed to outlast the Nixon administration. Apollo’s successor, the shuttle program, has had nearly 40 years’ worth of traction, in no small part because it became the critical link in building the space station and its international partnerships.

Why bother with human spaceflight at all?

For many people and countries, human spaceflight represents a pinnacle of human technological achievement and prestige.

Others point to potential economic and environmental benefits that could come from activities ranging from space tourism and tapping resources on the moon to use as fuel for fusion energy to mining asteroids or producing pharmaceuticals in microgravity conditions.

Still others argue that over the very long term, humans must become a multiplanet species to survive. Even without issues such as population growth, environmental degradation, and finite physical resources, Earth faces the risk of collision with a comet or large asteroid and of another Ice Age that would bury what today are some of the most economically and agriculturally productive swaths of Earth beneath two miles of ice.

Historians Roger Launius at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum and Howard McCurdy at American University in Washington have written that human civilization may have at most a few centuries to become a truly space faring species. Beyond that period, they say, it’s plausible that humanity will not have the collective wealth to support sustained space exploration and colonization.

---

Follow us on Twitter