Will crash of hypersonic Falcon HTV-2 set back Pentagon's ambitious plans?

Thursday's test flight of the Falcon HTV-2 ended with signals lost and a crash landing into the Pacific – but not before it sent engineers half an hour of flight data. The Pentagon hopes the design will allow a non-nuclear response to threats anywhere in the world, within one hour.

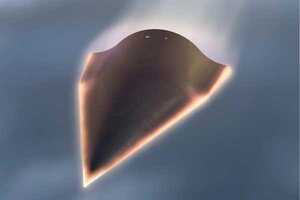

This artist's rendering shows the Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2). The Falcon HTV-2 is an unmanned, rocket-launched, maneuverable aircraft that glides through the Earth’s atmosphere at Mach 20, approximately 13,000 miles per hour.

DARPA/AP

The latest prototype in the Pentagon’s attempts to develop what is, in essence, a Mach 20 drone that can strike any target on earth within an hour, lasted no more than about 30 minutes before losing contact with ground stations Thursday.

That marks an improvement on the first prototype, launched in April 2010, which gathered data for about nine minutes before it began tumbling uncontrollably and crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

An arrowhead-shaped vehicle, the Falcon HTV-2 was laden with sensors to gather data on how the shape performs in the atmosphere as it travels between 17 and 22 times the speed of sound, or close to 4 miles per second.

This second mission was to have contributed "further insights into extremely high Mach regimes that we cannot fully replicate on the ground," said the project's program manager, Air Force Maj. Chris Schulz, in a prepared statement.

The initial flight plan was for the Falcon HTV-2 to separate from its rocket shortly after launch. Its built-in steering jets were to have oriented the craft to immediately reenter the atmosphere and glide to a splashdown near Kwajalein Atoll, part of the Pentagon's ballistic missile test range in the Pacific.

After the successful launch Thursday, however, officials at the Defense Advance Research Projects Agency (DARPA) lost contact with the vehicle during its glide stage.

Built by Lockheed Martin, the Falcon HTV-2 was part of the Pentagon's Conventional Prompt Global Strike Program, established during the Bush administration to provide a non-nuclear alternative for a quick response to attacks on US forces or imminent threats to US allies.

A scenario might go something like this:

A rogue state is making final preparations to launch a nuclear missile. The intelligence is reliable. The time to react is short.

What's the Pentagon to do?

How about launching an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) – but instead of a nuclear warhead, the missile would loft an explosives-laden, self-guided, hypersonic warhead capable of quickly ducking back into the atmosphere after the missile releases it.

In less than an hour after launch, the warhead would reach the nuclear-missile site.

While the US could currently respond with bombers or today's unmanned vehicles, they would have to be located within about 500 miles of a target to be able to respond within an hour of an attack, according to a 2008 National Research Council report evaluating the global-strike program.

The study found what it called credible scenarios under which the US would want to respond within an hour, but would not have the aircraft or ships close enough to do the job promptly.

Because the warhead would spend most of its transcontinental travel time within the atmosphere, advocates argue, it would be much less likely to be mistaken for a nuclear attack. Nuclear warheads also are launched from ballistic missiles, but spend most of their travel time arcing through space before dropping toward their targets.

Some analysts remain skeptical of an ICBM-based approach.

Assuming the technology for hypersonic flight can be perfected, "and that's a big if, this plan is less bad than some of the other ones rolled out," says Noah Shachtman, a fellow with the Brooking Institution in Washington who focuses on security issues and 21st-weapons systems.

It certainly beats another idea the Pentagon proffered – putting conventional warheads on submarine-launched Trident missiles. Because these missiles are currently nuclear-tipped, launching one – with any warhead – on the familiar up-and-down trajectory would very likely invite a nuclear response.

Ballistic-missile submarines often lurk relatively close to a potential adversary's shores, in order to reduce planning time for a retaliatory attack. If a country has a policy of launching on satellite detection of another's missile plumes, instead of waiting for the first warheads to fall, the opportunities for a nuclear exchange based on miscaiculation increases dramatically.

Putting conventional warheads on Tridents "is just flat out crazy," Mr. Shachtman says.

However, if the technologies DARPA is pursuing pan out, they could lead to cruise missiles capable of hypersonic flight. These could accomplish the same rapid-response goals with far less chance of being misindentified.

Having lasted longer than nine minutes, Thursday's Falcon HTV-2 mission likely will yield new, useful information on controlling aircraft at hypersonic speeds, as well as developing materials to withstand the intense heat and pressures generated by slicing through the atmosphere at 4 miles a second.