Bering Sea storm: Has global warming made Alaska more vulnerable?

Bering Sea storm winds are lashing the coast of Alaska. Sea ice extending out from the shoreline has protected the coast from past Bering Sea storm surges, but there is little such ice this year, and global warming is likely to blame.

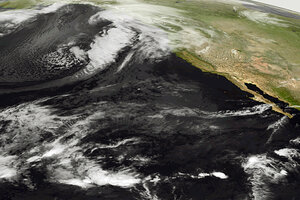

Bering Sea storm: This image provided by the NOAA-19 satellite's AVHRR sensor, shows the storm bearing down on Alaska in this infrared imagery on Wednesday at 5 a.m. ET. The storm is predicted to bring hurricane force winds and surge through the Bering Strait.

NOAA/AP

A powerful fall storm – the strongest since a mid-November storm in 1974 – is pounding Alaska's west coast with hurricane-force winds and a storm surge that in many places is expected to top eight feet above the high-tide line.

Although Alaska's coast is sparsely populated compared with other coastal regions in the US, low-lying areas host a number of native Alaskan villages, as well as the city of Nome.

Concerns for flooding and coastal erosion are compounded by a lack of coastal sea ice, which typically extends from the shoreline out toward the open ocean and is building at this time of year.

"There's not a lot of shore-fast ice yet," says Scott Berg, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service forecast office in Fairbanks. "This year it hasn't developed quite as extensively as it normally does."

This shore-fast ice, which builds in bays along the coast north of Nome, typically represents a first line of defense against coastal flooding when storms plow into the state's coastline. It reduces storm surge.

With this storm, however, less-extensive shore-fast ice leaves it vulnerable to the storm surge, Mr. Berg says. The surge likely would carry any available sheets of ice inland to act as a frigid battering ram against structures in its path.

Ocean and atmospheric conditions in the fall tend to foster some of the strongest storms in the northern reaches of the North Pacific, forecasters say. It's been lights-out at the North Pole since mid-October, which provides a source of frigid air. Yet the North Pacific still retains much of its summer heat, which it releases back to the atmosphere.

The stark contrast between warm, moist ocean air and its frosty polar counterpart provides the energy that drives storms such as the system that is affecting Alaska and eastern Siberia, notes Jeff Masters, a former hurricane hunter with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and founder of the Weather Underground meteorology website.

The storm's broad expanse over open water as it approached the Bering Straight also allowed it to generate large, long-lived swells that ride atop the surge.

While the storm is weaker than the '74 event, it appears to fit into a long-term pattern with a global-warming connection

Dr. Masters notes that several studies over the past several years have documented an increase in the number of these intense wintry storms in the northern hemisphere over the past century, with a marked upward swing beginning in the mid-1960s, as the global climate has warmed.

In addition, researchers point to global warming as a contributor to a decline in summer sea ice in the Arctic, the foundation on which winter ice rebuilds.

On Nov. 2, the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo., noted that the 2011 summer melt season ended with the second lowest summer sea-ice extent since satellites began tracking sea ice in the late 1970s.

Some researchers project that these winter storms will decline in number, but increase in strength and appear at ever higher latitudes should the climate continue its long-term warming trend, as most climate scientists expect. Its a pattern that mirrors some projections for hurricanes, typhoons, and other tropical cyclones during this century.