Solar storm buffets Earth: How protected is the US power grid?

Peak impact of the solar storm was expected Tuesday. Only a few of the strongest storms have a serious impact, but modern society is more dependent on power grids than ever.

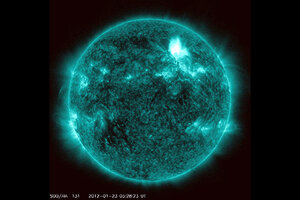

Solar storm: This colorized NASA image, taken Monday, from the Solar Dynamics Observatory, shows a flare shooting out of the top of the sun. It was taken in a special teal wavelength to best see the flare.

NASA/AP

Power-grid operators nationwide are on high alert Tuesday as gale-force geomagnetic winds from a solar storm sweep across the Earth – creating potentially dangerous electrical currents that, if severe enough, could damage the US power grid.

The impact of this solar geomagnetic storm – called a “coronal mass ejection” by scientists – is being measured by satellites orbiting the Earth. It is the strongest such storm to hit Earth since 2005.

Still, it was expected to be moderate in intensity, compared with more severe events in the past, with only mild impacts on the power grid, solar storm experts said. Peak impact was expected Tuesday between morning and late in the day, solar weather experts said.

After the flare showed up on satellite sensors Sunday, solar storm advisories were sent by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to the nation’s independent system operators that oversee regional grid reliability in the nation 10 big power markets.

Beyond problems with satellites and radio communications, power generators and transmission line operators were advised to put the portions of the grid they control in a more defensive, robust posture. The idea is to gird for the impact of billions of tons of charged solar particles striking the Earth's magnetic field at two million miles per hour.

“We do not expect an impact to the bulk power system, however utilities are monitoring their facilities, as usual, for any abnormal energy flows and are prepared to take all appropriate actions to maintain reliability of the bulk power system,” writes Kimberly Mielcarek, spokesman for the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) in an e-mail. “We’re conferring with NOAA counterparts as needed, and sharing information with the North American bulk power system reliability coordinators.”

Intense debate has swirled over the issue of solar geomagnetic storms – and what, if anything, to do about these infrequent events beyond reactive, defensive actions. Most such storms have little impact on the Earth. Only a handful have had any serious impact over the past century. Still, the US and other modern societies are more dependent on power grids than ever – and damage to the grid could be severe in some cases.

The power grid is 10 times larger than it was in 1921, when the last solar super storm hit, effectively making it a giant new antenna for geomagnetic current. A far stronger solar outburst could overload and wreck hundreds of critical high-voltage transformers nationwide, blacking out 130 million people for months and costing as much as $2 trillion, according to a 2010 Oak Ridge National Laboratory study.

In 1859, the strongest geomagnetic storm on record made telegraph systems worldwide go haywire. So much induced current surged through the lines that some telegraph offices caught fire and wires melted. Most recently, a far-weaker 1989 solar storm knocked out power to millions of people in Quebec for about nine hours. Farther south, a large transformer at the Salem Nuclear Power plant in New Jersey was wrecked by the same event.

Should big transformers that would be most affected have surge protectors put on them to prevent them from burning out during a severe storm? How much would that cost? Should the federal government mandate such preparations?

Congress has repeatedly held hearings on the issue. In the previous session of Congress the House of Representatives overwhelming approved legislation that would have mandated that power-grid operators take action. But the Senate did not take up the matter – and new legislation is still sitting, waiting for passage.

For its part, NERC issued a 2010 report warning that geomagnetic storms, along with cyberattack and electromagnetic pulse attack with a nuclear weapon – were three high-impact but low-probability threats worth guarding against. Last May, NERC issued an advisory to regional power system operators identifying an array of steps available to them when NOAA issues warnings of a geomagnetic storm.

Practical actions that can be taken, for instance, include purchasing power from generators closer to where the power is being consumed rather than buying blocks of power that have to be sent on transmission lines that span several states, a move that enhances the stability of the grid by helping maintain necessary voltages on the system.

But debate over just how much damage would occur from such as storm is almost as intense as the storm itself. While experts are reported to largely agree that such storms could knock out big sections of the grid, there is sharp disagreement over how much damage it would do and whether big transformers would burn out and cause longer-term, wide-scale damage to the US economy, US experts say.

“We want to make sure that we aren't rash in our judgments,” says John Kappenman, the solar storm expert who conducted the seminal Oak Ridge National Laboratory study that warned of a worst-case scenario that could put 130 million people out of power for months or longer and cost more than $1 trillion.

To prevent such an unlikely but costly event, blocking devices, the equivalent of surge protectors for those big but possibly vulnerable transformers, could be installed at a cost of around $1 billion nationwide – a small cost when spread across households – and could be a saving grace, Mr. Kappenman says.

“Ultimately we have to figure out the right thing that needs to be done,” he says. “We absolutely have to get this right, because we can't wait for a big storm to learn all the things we need to learn. It's too large a consequence for society.”