Ferguson shooting: Why hasn’t the police officer been arrested?

The death of Michael Brown raises this question: Should there be a different legal standard when it comes to arresting a police officer vs. an ordinary civilian? Law professors are sharply divided on the answer.

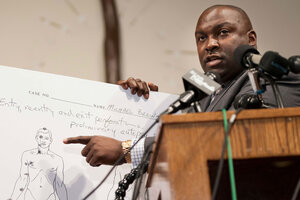

Brown family attorney Daryl Parks points on an autopsy diagram, on August 18, 2014. The family of Michael Brown, a teenager shot dead by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, paid for an independent autopsy which was carried out by Dr. Michael Baden, former chief medical examiner for the City of New York.

REUTERS/Mark Kauzlarich

[Updated Aug. 21, 1:30 EDT] After an autopsy by Michael Brown's family was made public Monday, family attorney Benjamin Crump quoted the bereaved mother as asking: “What else do they need to arrest the killer of my child?”

Just a day earlier, appearing on the talk show "Meet the Press," Harvard Law School Prof. Charles Ogletree said that police officer Darren Wilson should be taken into custody as he shot a man and “no one knows why he did it.”

“I think the first thing that needs to happen: you need to arrest Officer Wilson,” Professor Ogletree said. “He shot and killed a man — shot him multiple times — and he’s walking free.”

Should there be a different legal standard when it comes to arresting a police officer vs. an ordinary civilian?

Law professors strongly disagree on the answer, especially in the Michael Brown case. And the question isn't simply academic when protestors in Ferguson say they won't go home until they see "justice" done. Might an arrest ease tensions?

While anyone can be arrested, US citizens usually can't be kept in custody beyond 24 hours (depending on circumstances and state laws) unless they are charged with a crime. For someone to be charged, there must be "probable cause" – that it’s more likely than not – that a crime has been committed.

To determine whether probable cause exists, the St. Louis County prosecutor impaneled a grand jury and the F.B.I. deployed almost 50 agents to the scene – an unusually high number. When the grand jury completes its investigation, the local prosecutor will decide whether to charge Wilson with a crime, a step that could be as early as this week, Reuters reported.

Harvard Law Prof. Alan Dershowitz sides with the St. Louis County prosecutor – not his colleague Ogletree: “We should not arrest [Officer Darren Wilson] until there’s a substantial level of proof of criminality,” even if it appeared that the police acted improperly.

“Based on what I know, I would hold off,” says Professor Dershowitz. “The one thing I would insist on is that you never ever make an arrest because of crowd violence,” he says, alluding to the daily protests and rising political pressure.

Dershowitz compares the Michael Brown case to the 2012 Trayvon Martin incident – when a neighborhood watch volunteer was acquitted of using deadly force against an unarmed black man – saying that the state should not have filed charges against defendant George Zimmerman.

“It was a terrible miscarriage of justice in that case,” he says. “[Mr.] Zimmerman was arrested and prosecuted because of mob violence,” suggesting that the same issue could be at play here.

But Dershowitz starts to waffle a bit as he considers the family's privately contracted autopsy report. He says that Ogletree may be right in calling for an arrest since the autopsy showed no gunshot residue on Brown’s body. That suggests that Brown was at least two-feet away, undermining the officer’s self-defense claim.

Dershowitz’s former student, American University Washington College of Law Prof. Angela Davis, pushes back against her onetime instructor.

She blasts Dershowitz’s remarks on the Trayvon Martin case, saying that in both cases the shooter benefited from his white skin-color.

“There are tremendous racial disparities in our criminal justice system and they have been well documented. Similarly situated individuals in our criminal justice system are treated differently based on race. That racial bias was definitely an issue in the Zimmerman case and I believe that it’s an issue in this case.”

She also diverges from Dershowitz on the matter of probable cause. “There’s definitely probable cause to believe that he committed some form of criminal homicide,” says Professor Davis.

In this case, at least two eyewitnesses say that Brown was standing in the street with his two hands in the air, and did not pose a danger to the officer or anyone else. In other words, probable cause for arresting Wilson for killing Brown.

It's not uncommon for bystander accounts to be contradictory. “[Police officers] will still arrest you if some of the witnesses confirm that you committed the crime. If there’s a jury trial, the jury will decide who is telling the truth,” says Davis.

Given the eyewitness testimony, Davis suggests that the St. Louis police have not arrested Wilson because they either don’t believe the accounts of certain witnesses or are giving their colleagues preferential treatment.

“Police officers are rarely arrested and indicted for a crime for their actions in the line of duty,” she says. “They are never arrested right away,” Davis says, acknowledging that despite the greater legal latitude afforded to police officers, “they can’t use deadly force in all circumstances.”

Even when someone kills in self-defense – the imminent fear or danger of bodily harm and death – the suspect is usually arrested first and then may be acquitted in a trial, she says.

“If the investigation reveals that [Brown] was standing in the street with his hands up not charging at anybody, not posing a danger to the officer or anyone else, that’s more than probable cause that he committed murder,” says Davis.

Davis and Dershowitz do agree on one thing: They're skeptical that the impaneled St. Louis grand jury will reach an impartial decision.

“In theory, it sounds good. The problem is that the grand jury is totally controlled by the prosecutor,” she says, listing problems such as the panel's private proceedings, no defense attorney present, and prosecutors don’t need to offer exculpatory evidence – or facts favorable to the defendant.

In this case, the St. Louis district attorney Bob McCullough has worked alongside Officer Wilson. Davis questions whether he can be impartial in the Brown case.

“[Mr. McCullough’s] father was killed in the line of duty” as a police officer, says Davis, adding, “he wanted to be a police officer himself until health issues intervened” and that he actively supports the local police benevolent association.

On the other side of the debate stands University of San Diego law school Prof. Lawrence Alexander, who says it's “irresponsible” for other academics to call for an arrest. “Those people don’t know the facts. You can’t just call someone to be arrested when you don’t have evidence that they committed a crime,” he says.

If Wilson is arrested, Professor Alexander weighs in on the possible criminal charges. Because the prosecutor must prove beyond a reasonable doubt – a high legal standard – that Wilson is guilty, he will most likely not be charged with first or second-degree murder.

If anything, he would be charged with voluntary manslaughter or lesser offenses, says Alexander, but added that it was premature to say.

“All I’ve heard is conflicting evidence and the autopsies aren’t completed yet, says Alexander. “It would be extraordinary to bring charges this early,” and arrest the officer.

Alexander notes that the local investigation could be compromised due to the district attorney’s long-time working relationship with the police, likening it to “prosecuting a member of your family.”

The professor also sounds surprised by the amount of resources and number of FBI agents assigned to the case.

“If you’ve got a complex racketeering or money laundering scheme, that’s when you might need a number of agents. But this is a simple street use of force and it doesn’t take a battalion of investigators,” Alexander says, adding, “I can’t imagine what they would be doing instead of stepping on each other.”

Prof. David Klinger of the University of Missouri-St. Louis also questions Ogletree’s call to arrest the officer.

“What does he know? Has he seen the case file? Is he privy to the investigation,” asks Professor Klinger, saying that unless Ogletree reviewed witness statements, ballistic forensics and the autopsy, he should not call for an arrest.

Klinger adds that such a demand “provides legitimacy to those in the mob… those who are looting, burning, throwing rocks and bottles at police, at reporters.”

He also cites the recent past of white lynch mobs hanging black men on trees to argue against immediately arresting the officer.

“I find it to be the height of irony that we have a mob mentality demanding that an individual be punished when we don’t even have the facts so far. Let’s allow the process – for which we fought the civil rights struggle – let it run evenly,” says Klinger.

Klinger described how police officers are permitted to shoot in two scenarios, in self-defense or for another person. The second scenario is to prevent a suspect who committed a violent felony from escaping, even if an officer only has probable cause on what happened.

The professor has conducted research on past police shootings and concluded that the “vast majority” are justified, adding that even in a questionable altercation, courts rarely prosecute police officers for using deadly force.

Before arresting the officer, Klinger reiterates that police officers have the same constitutional rights as anyone else.

But former St. Louis police chief Dan Isom, now a professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, echoed Havard's Ogletree that if Officer Wilson were a typical suspect in a homicide, based on known public evidence, he could have been arrested.

But his status as a police officer – and not a civilian – may explain why Wilson has not been taken into custody.

The key question, is “at what point in time… do you pivot from the police officer acting in the performance of his duty trying to apprehend the subject to the officer being the suspect and the person he shot, the victim,” Professor Isom asks.

Based on the evidence that has already been gathered and the fact that a grand jury was impaneled, a case could be made against the officer but that it’s not overwhelming, says Isom.

He also defended the notion that police officers should be treated differently than civilians when accused of homicide. "[If not], whenever an officer used force, we’d consider him a suspect and we’d arrest him immediately,” the former police chief says.

With President Barack Obama overseeing the racially charged federal investigation and the first black Attorney General visiting St. Louis Wednesday, this incident has raised anew questions about the role of race in the criminal justice system. Are police treated differently by the justice system when they kill a black man than when they kill a white man? That remains unclear.