Meet Baxter, your new robotic co-worker

Recent leaps in computer processing speeds and sensing capabilities have given rise to new possibilities for how robots can work in concert with people.

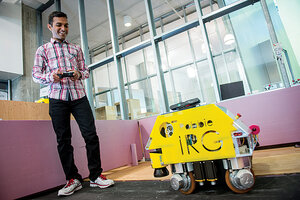

Vaibhav Unhelkar demonstrates Robbie, a robot being developed to safely work with humans, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

ANN HERMES/STAFF

Southington, Conn.; and Cambridge, Mass.

Nestled into a suburban industrial park, one of Vanguard Plastics’s most dependable employees methodically toils away inside the 22,000-square-foot factory day and night. Baxter, as he’s known, is highly focused, remarkably consistent, and tireless. Perhaps his best feature is his ability to work with others.

However, Baxter isn’t quite like any of his co-workers. He’s a $25,000, 300-pound robot from Boston-based Rethink Robotics. But Baxter isn’t really like the other industrial robots at this factory in Southington, Conn., either. Unlike the other machines at the plastics maker, Baxter works right alongside his human co-workers.

As he retrieves stacks of 10 freshly molded plastic cups from a conveyor belt, several workers bustle about him. When Chris Budnick approaches him, a crown of yellow LEDs lights up around the robot’s “head.”

“That’s Baxter’s way of letting me know that he sees me,” Mr. Budnick says.

Baxter keeps working – until Budnick, who is president of Vanguard, reaches for a stack himself. The robot’s 40-pound arm slows as it nears Budnick’s and does not resume full speed until the path is clear.

“That Cartesian robot over there,” Budnick says, pointing toward a massive machine encased in polycarbonate plastic, “will run right through you and never know anybody was there.”

Baxter is one of the first of a new breed of industrial robots, known as collaborative robots, or cobots, designed to work alongside people. Until recently, industrial robots had to be separated from human workers because of their size and speed. However, recent leaps in computer processing speeds and sensing capabilities have given rise to new possibilities for how robots can work in concert with people.

These are some of the first toddling steps in the development of personal robotics, the first glimmers of promise that the robot butlers and companions that Hollywood has been advertising for decades may actually come home.

Factories are ideal settings for working out the kinks of interactive robotics, says Julie Shah, director of the Interactive Robotics Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Manufacturing tasks tend to be repetitive and follow regimented schedules – therefore, programmable. They also tend to include a variety of tasks that could benefit from the strength and tirelessness of a robot as well as the reasoning and flexibility of a person, Professor Shah says.

Outsourcing physically arduous and tediously repetitive tasks to this new breed of cobots can not only improve task time, but also reduce human idle time and improve worker satisfaction, she says.

At Vanguard, before Baxter came along, a person had to monotonously stack those cups – again and again and again.

It’s “repetitive and incredibly boring work,” Budnick says. There is still a person monitoring Baxter’s work, who also makes sure a bagging machine functions properly and randomly inspects the cups for microscopic flaws.

Budnick is careful to clarify that Baxter did not replace a human employee. That’s a touchy subject for manufacturers and robotics researchers alike.

Machines have been displacing people from their jobs since the days of the printing press. In the past few decades, the rise of computers has virtually eliminated entire professions and whittled away the job market of others.

According to a Pew Research Center poll released in August, nearly half – 48 percent – of some 2,000 technology experts surveyed worry that robots and digital agents will significantly displace human workers and lead to increased income inequality and higher unemployment rates as soon as 2025.

“What are people for in a world that does not need their labor, and where only a minority are needed to guide the ’bot-based economy?” Stowe Boyd, futurist and analyst for Gigaom Research in New York, wrote in his response to the survey.

Many in the robotics community insist they are building machines that are designed to augment human work, not replace it. Shah’s lab has a stated vision that focuses on “harnessing the relative strengths of humans and robots to accomplish what neither can do alone.”

“There is a lot of work that people do today that they shouldn’t be doing in terms of heavy lifting and work that’s not ergonomic,” she says. At the same time, “a lot of work requires flexible decisionmaking. It requires a sort of artistry or a skill that you develop through experience.”

Shah has experimented with the use of robots in painting airplane fuselages as an example of a physically demanding task that robots can carry out under human supervision.

Automotive factories have relied on automated machines to do much of the heavy lifting since the 1960s, but again, those robots tend to weigh hundreds, even thousands, of pounds and move so fast that they could easily run a person over.

Foremen at a BMW factory contacted Shah’s group inquiring if the scientists could develop a robot that could scoot around the factory floor delivering heavy parts to people working on a moving assembly line.

Vaibhav Unhelkar, a PhD student working in Shah’s lab, took on the challenge and is currently working to adapt a stout robot, aka Robbie, into a strong but sensitive workhorse that can both assist and look out for its human co-workers.

Mr. Unhelkar equipped Robbie with laser sensors that can detect an upcoming obstacle, and he programmed the robot to stop short of crashing, even if it receives a remote-control command to continue driving forward.

For people and robots to truly collaborate – in either the factory or the home – robots need to be able to adapt to the presence of people and carry on working. For that to happen, robots need to not only sense a person’s presence, but also formulate some prediction about what the person might do next.

People are very good at picking up on subtle cues in others’ body language that indicate where they might go next. That intuition is formed by years of experience watching other people move. A robot’s experience is limited to what people have written into its program.

Claudia Pérez D’Arpino, another PhD candidate in Shah’s lab, is working to compile a digital library of people’s movements using a motion-capture system, in which cameras register and catalog the movements of volunteers placing toy blocks into one of four boxes. Ms. Pérez D’Arpino wrote a program that can predict which box a person is moving toward just 4/10ths of a second after the person begins to move – with 80 to 90 percent certainty.

Pérez D’Arpino’s and Unhelkar’s projects each represent one small piece of a greater robotics puzzle. Thanks to the collaborative nature of the open-source ROS (robot operating system) developed by robotics pioneer Willow Garage, their contributions can be combined with those of roboticists around the world.

At Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., electrical and computer engineering professor Avinash Kak is interested in bringing interactive robots out of the industrial setting into more varied environments such as the home or office.

Most computer vision interprets sensory data as simple geometric shapes, Professor Kak notes. So how does a robot make the leap from seeing a rectangle, for instance, to actually identifying it as, say, a box of tissues? “That’s the million-dollar question that goes to the crux of the whole matter,” Kak says. Robot vision works only when the objects are simple and geometric, and you have stored models of that geometry in the computer, he says.

This limitation in computer vision is one reason the robots that are currently available for personal use are dedicated to specific tasks. For now, the multipurpose robot that preps dinner, cleans the gutters, and feeds the goldfish remains out of reach.

Chances are, the first people to employ personal robots at home won’t be busy parents seeking an extra pair of hands to manage the house and wrangle the kids anyway, says Maja Matarić, director of the Robotics and Autonomous Systems Center at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

She believes the first owners of personal robots are more likely to be some of the most disenfranchised members of society: people with disabilities and senior citizens.

At her lab, Professor Matarić and her colleagues are developing robots that can serve as companions for people who require some level of care but wish to remain in their home. “They may have a therapist coming a couple times a week, and well-intentioned, loving family members checking on them periodically, but that’s not enough,” she says.

Matarić’s vision is somewhat similar to that portrayed in the 2012 film “Robot & Frank,” in which a loving but busy son buys a robot companion for his forgetful and occasionally confused father.

In the movie, which was loosely based on Matarić’s work, the robot regularly encourages Frank to keep his mind busy, takes him on walks, and urges him to eat better.

Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of machines providing companionship.

In a review of the film, Roger Ebert referred to the robot as “a household appliance more relentless than an alarm clock.” An April Pew Research Center poll found that 60 percent of Americans were concerned about the possibility of robots taking over primary care for seniors and invalids.

Matarić argues that socially assistive robots are designed to supplement human interaction, not replace it – a pressing need given the aging baby boomer population and a dearth of good, affordable elder care.

“There is clear evidence that people are able to bond with robots,” Matarić says. She points to a 2010 Georgia Tech study that showed that owners of iRobot’s Roomba vacuum become emotionally attached to their vacuums – naming them and even refusing to accept replacement vacuums if they break. “What’s to say a robot couldn’t be a companion for people who are truly lonely?” she asks.