All teachers fired at R.I. school. Will that happen elsewhere?

All the teachers at Central Falls High School in Rhode Island were fired by the board of trustees this week. More such cases are likely to arise across the US in the coming year because of pressure from the Obama administration – and the incentive of billions of federal dollars.

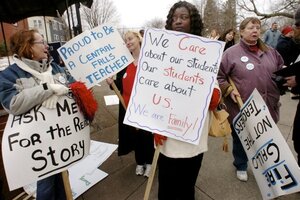

Teachers protest outside Central Falls High School in Rhode Island. The school committee voted to fire every teacher, the principal, and other staff at the high school at the end of the school year.

Butch Adams/The Pawtucket Times/AP

A small, high-poverty school district in Rhode Island is now ground zero for some of the most explosive debates over reforming America’s worst-performing schools.

To the dismay of many local and national union members, all the teachers, the principal, and other staff of Central Falls High School were fired by the board of trustees this week. The move is part of a dramatic turnaround plan proposed by the superintendent and approved by the state education commissioner.

Because of pressure from the Obama administration – and the incentive of billions of federal dollars – more such cases are likely to arise across the United States in the coming year.

Advocates of the “turnaround” approach say it’s a way to remove bad teachers or change a culture that makes it difficult for good teachers to work effectively. But teachers feel scapegoated. And there’s no clear-cut research guaranteeing that student test scores will improve when schools are reorganized with new staffs.

Will more superintendents clean house?

“This will be a canary in the coal mine,” says Frederick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Such dramatic moves are likely to multiply as “an increasing crop of no-excuses superintendents and state commissioners” take the view that “it’s essential to clean house” to improve persistently failing schools, he says.

US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan applauded the Rhode Island decision this week. But Randi Weingarten, American Federation of Teachers president, shot back with a statement that “firing all of the teachers is a failed approach and will not result in the kinds of changes necessary to improve instruction and learning.”

In 2009, 48 percent of Central Falls High School students graduated after four years, compared with a state average of 75 percent, according to a state education department spokesman. This past fall, 7 percent of 11th graders tested at the proficient level in math, 55 percent in reading.

The firings take effect at the end of the academic year. No more than half the staff can be rehired under such turnarounds, according to US Department of Education guidelines for $3.5 billion in School Improvement funds distributed to the states. Those funds – for schools with a certain level of poverty among the student body – require states to improve the worst 5 percent of such schools. Similar strings are attached to more than $4 billion in competitive “Race to the Top” funds. (For more on "Race to the Top," click here.)

Options for low-performing schools

State and district officials have four options for such schools: The turnaround model, which includes improving instruction as well as replacing staff; reopening a school as a charter or under an approved management organization; closing a school altogether; and transforming the school through such measures as intense teacher development and extended learning time for students. (Monitor report: Which states are innovative in education? A new report card.)

The turnaround plan in Central Falls came after negotiations between the district and the local union over other improvement approaches broke down. The five other worst schools in Rhode Island are in Providence, which faces a March 17 deadline to submit improvement proposals.

School superintendents in small rural or suburban districts don’t always have a pool of better teacher candidates to turn to, or better schools to send students to if they close a low-performing school, says Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators.

The Obama administration is “pushing the envelope” more than would be traditionally expected by a Democratic administration supported by unions, Mr. Domenech says. But, he adds, there are also efforts under way for state superintendents and union representatives to reach some compromises for revising union contracts to support school improvement.

It’s important to address the problem of persistently failing schools, but after “the big dramatic gesture – fire the teachers – the next step is equally or more important,” says Jack Jennings, president of the Center on Education Policy. “Are better teachers going to be hired?... Are kids going to learn more?”