Mental health: Is that a job for schools?

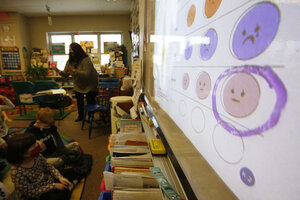

Second grade teacher Melissa Shugg teaches a lesson at Paw Paw Early Elementary about thoughts, feelings, and actions on Dec. 2, 2021, in Paw Paw, Michigan.

Martha Irvine/AP/File

Should mental health concerns be handled by schools?

Numerous statistics – and students themselves – point to the significant struggles many young people in the United States are experiencing. In an effort to help, federal and state governments are allocating hundreds of millions of dollars in new funding to cover everything from training more providers to running mental health awareness programs.

Advocates suggest the school building is the most accessible and least stigmatizing place for mental health support. But others are raising concerns about how many tasks often-overburdened schools can handle.

Why We Wrote This

Care for students and their mental health needs is increasingly falling on schools, which have a number of advantages for dealing with a growing crisis. But concerns about ethics, privacy, and piling on educators have some people wondering: Who actually should bear the burden? This piece is part of a collaboration across seven newsrooms, in partnership with the Solutions Journalism Network. Read the other articles here.

“You do at some point have to ask some very basic questions about what are the expectations that we have of this thing called school,” says Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow focused on education at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank. “No one is suggesting schools should not be concerned about kids’ overall well-being. But is this the proper place in civil society for mental health services to reside?”

The recent expansion of offerings has spurred more discussion about the ethics involved in supporting students – how much schools and mental health should intersect and where the guardrails should be. A school board in Killingly, Connecticut, for example, this year drew the line at allowing the superintendent to establish a mental health clinic in a high school.

Determining what services to offer in schools is a question that “has to be answered 14,000 times in 14,000 local school districts,” Mr. Pondiscio says, adding that people will disagree on the appropriate use of government dollars for mental health in publicly run schools.

A scramble to help

During the first year and a half of the pandemic, 92 state laws were enacted to address youth mental health through school-based programs, according to an analysis by the nonprofit National Academy for State Health Policy. The federal gun safety bill passed by Congress on June 24 includes related funding.

President Joe Biden wants to double the number of mental health professionals in schools. Already schools have seen a 65% increase in social workers and a 17% increase in counselors compared to before the pandemic, due to use of American Rescue Plan funds to increase hiring, according to the White House.

Even so, most schools are understaffed. The American School Counselor Association, for example, recommends a counselor-to-student ratio of 1:250. The association reports the national average was 1:415 in the 2020-21 school year.

The flurry of recent activity is being driven by experts – and students themselves. The U.S. surgeon general issued an advisory in December 2021 warning of a youth mental health crisis. Nearly three-quarters of young Americans say the country as a whole is experiencing one, according to a spring 2022 survey by Harvard Youth Poll. Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns this week debuted a two-part program on PBS, “Hiding in Plain Sight: Youth Mental Illness,” which tells the stories of more than 20 young people in the U.S.

Various theories circulate among researchers as to why mental health has been declining, including the influence of social media, changing parenting styles, and a seemingly unstable world confronting climate change, social justice, and political polarization.

Schools are a natural place to address these issues, many Americans say, as mental health services have existed there for years. The National Association of School Psychologists was formed in 1969. School-based health centers that provide pediatric, dental, and mental health services in schools were also started in the 1960s and 1970s.

“When we ask families and students, overwhelmingly most prefer to receive support in the school building, in part due to proximity and convenience. Students and parents are less likely to miss time from school and work, and a lot of families say it’s less stigmatizing,” says Sharon Hoover, co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health and professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

A 2017 study of mental health services in elementary schools by researchers at Florida International University found “school-based services demonstrated a small-to-medium effect in decreasing mental health problems, with the largest effects found for targeted intervention.”

Dr. Hoover says research supports the establishment of multitiered systems of support in schools. In this model, schools provide such services as universal lessons or wellness checks for all students and more targeted, intensive support for those students identified as needing additional assistance.

How that looks in schools varies.

For instance, all students in a school with a multitiered system of support receive “tier one” support, like classroom lessons or assemblies on mental health awareness. A smaller number of students identified as needing “tier two” support might participate in group sessions, led by school counselors, on dealing with grief or stress. An even smaller number of “tier three” students receive more intensive treatment, such as individual therapy with trained school staff, or are referred to an outside provider.

In a database maintained by the National Center for School Mental Health, roughly 15,000 schools self-report that they have comprehensive school mental health systems. That’s about 15% of K-12 public schools in the United States.

Hawa Cabdullahi, a rising senior in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, has seen her high school, which has 3,000 students, promote mental health support more since the pandemic began. It can take months to get an appointment with the school’s sole psychologist, but teachers now allow students to take walks more during class and accommodate assignment deadline shifts if needed. The school also created a break room for qualifying students to use.

“Things are getting better with mental health resources over the past years,” she says. “I feel that the main issue is adults not listening or certain people who have the power to change things not wanting to spend the money on it and not wanting to improve the general livelihoods of people who are impacted by mental health struggles every day.”

“At the table from day one”

Even before the pandemic, increased calls for steps like universal screeners, or well-being checks, were raising concerns about student privacy records. Some parents in Florida worried that their children’s mental health records would be held against them after the state enacted a law in 2018 in the wake of a mass school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School that required informing schools during new student registration if a child had ever been referred for mental health services, according to Kaiser Health News.

“Parents and family members should be at the table from day one with how do students access visits, how do schools get consent for services, how should schools and providers inform families if a student screens positive,” Dr. Hoover says. “Families should have a choice about if and how and where they receive mental health support.”

Informed consent and clinical competence are two ethical issues that mental health providers and families should be aware of when thinking about offering or receiving mental health treatment in a school setting, says Jeffrey Barnett, a professor of psychology at Loyola University Maryland.

School staff need proper training and oversight, he says. For instance, if teachers are administering universal mental health screeners to students, “are they being trained or is it seen as just another task to add to their workload?” He believes students and staff should all be trained in mental health awareness and know what referrals they can make if someone exhibits signs of needing help.

Asking teachers to take on extra training about mental health and to incorporate more social and emotional lessons is a feature of schooling that’s largely been expanding without enough examination, says Mr. Pondiscio of the American Enterprise Institute.

“I think there are legitimate reasons to be concerned about mission creep, that we are changing the job of the teacher to be as focused on children’s mental health and well-being as the academics. It’s one thing to have it baked into the pie and another thing to make it a deliverable and a piece of the curriculum as compared to an endemic part of school culture,” he says.

Dr. Hoover suggests that responding to student needs should be a “public health approach.” That might involve schools providing lessons for everyone on regulating emotions as well as creating calm corners for students within buildings. It also might mean building a wide range of partnerships with people outside schools, including community health providers, faith groups, and other organizations important to youth.

“The mental health of our young children can’t fall on the shoulders of school psychologists, social workers, counselors alone, nor should it,” says Dr. Hoover. “It should really be a shared responsibility of everyone, including families, teachers, and the students themselves. They want to help each other.”