Mitt Romney tax return poses a challenge: how to talk about his wealth

With the release of the Mitt Romney tax return, which showed nothing illegal, the worst may be over for the candidate, but GOP analysts say he needs to develop a better message about his money.

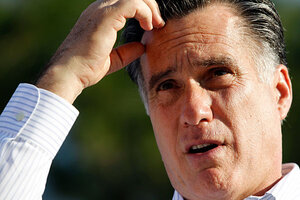

Republican presidential candidate, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney stands in front of a foreclosed home in Lehigh Acres, Fla., Tuesday.

Charles Dharapak/AP

Washington

The release of Mitt Romney’s tax returns Tuesday comes at a risky moment for the mega-wealthy Republican presidential candidate.

Mr. Romney has been sinking in polls of GOP voters – in part, because he behaved so uncomfortably and indecisively in debates last week over questions about putting out his tax returns. Now that he has released two years’ worth – 2010 and an estimate for 2011 – the worst may be over.

Nothing illegal or surprising has emerged. He had already revealed that he paid a low effective rate (about 15 percent), that he had accounts in foreign countries (on which he paid US taxes), and that he donated generously to the Mormon Church.

Democrats argue that Romney needs to reveal far more than just two years’ of returns. Some want to see returns going all the way back to his days as CEO of Bain Capital, a private equity firm that he co-founded in 1984 and left in 1999. And if Romney manages to win the GOP nomination, the specter of Bain, and the vast wealth it afforded Romney, will continue to hover over his candidacy.

But for that to matter, he needs to reach the nomination. His immediate task, heading into the crucial Florida primary on Jan. 31, is to put the tax-return episode behind him and develop a better message about his wealth, Republican analysts say.

“The real challenge for Romney is not the size of his bank account or the numbers in his tax return,” says Dan Schnur, communications director of the McCain campaign in 2000. “He needs to figure out a way to talk about his money in a way that isn’t so uncomfortable and so defensive.”

Voters know that he’s wealthy and that’s not necessarily a problem in itself, says Mr. Schnur, who is neutral in the 2012 race. “His challenge is to discuss his assets in a way that works to his benefit rather than his detriment,” says Schnur.

The exit polls from last Saturday’s Republican primary in South Carolina were telling for Romney. The winner, Newt Gingrich, won all income groups except those earning more than $200,000 a year. That may be more a function of Mr. Gingrich’s populist rhetoric and more consistent record as a cultural conservative than his wealth gap with Romney. Gingrich, after all, is also a wealthy man.

But in a tough economic environment, Romney has struggled to convince voters he understands their pain and fears. South Carolina’s unemployment rate stood at 9.5 percent in December. Florida’s is even higher, at 9.9 percent. Romney’s off-the-cuff statement about the money he earned from speaking fees – “not very much” – was also telling. Between February 2010 and February 2011, he made more than $374,000 from speeches, many times a typical family’s income.

Scrutiny of Romney’s massive net worth – between $190 million and $250 million – comes at a time of intense public attention to the growing gap between rich and poor, the 1 percent versus the 99 percent, in the parlance of the Occupy movement.

A Pew survey last month found that the public believes the wealthy are not paying their fair share in taxes.

“The resonance of the 15 percent level of taxation has to do with the sense of fairness,” says Andrew Kohut, president of the Pew Research Center. “People are very concerned that the government writ large is unfair.”

The risk for Romney is that he becomes the poster child of a system perceived as unfair, even though he is paying what he legally owes. The timing of his tax return release plays right into President Obama’s hands. In his State of the Union address Tuesday night, the president will focus on the inequality of the tax system. He is expected, once again, to call for the reform of a tax code that allows some of the wealthiest Americans to pay a lower tax rate than their secretaries.

In the audience will be Debbie Bonasek, billionaire Warren Buffett’s secretary for almost two decades, who is taxed at a higher rate than her boss. Mr. Buffett supports the principle – dubbed “the Buffett rule” – of changing the tax code to address that aspect.

Even though the timing of Romney’s tax return release is not ideal, analysts say he and his campaign could not wait any longer.

“They raised suspicions by delaying the release,” says Steven Schier, a political scientist at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn. “What they want is for this to be a nonissue that no one cares about.”