Syria, under pressure, drops bid for UN rights council. Is that progress?

Syria cuts a deal and gives up its quest for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council, for now. Some see a victory for higher standards on human rights, but critics of the body say the selection process is still flawed.

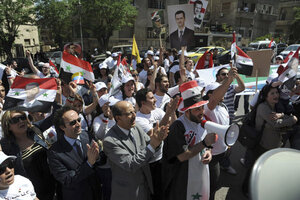

In this photo released by the Syrian official news agency SANA, Syrian pro-government supporters carry pictures of Syrian President Bashar Assad during a sit-in in front of the US Embassy in Damascus, Syria, on May 11.

SANA/AP

Washington

Syria ended its quest to join the United Nations’ Human Rights Council on Wednesday, bowing to pressure from the United States and other Western powers who had railed against a government seeking the seat even as it carries out a repressive campaign against its own citizens.

Syrian and Kuwaiti diplomats announced at the UN in New York that the two countries will switch their candidacies for the council – Kuwait will take Syria’s slot in elections next week, while Syria will now wait and go for the seat in 2013 that Kuwait was expected to seek.

Because of minimal competition for seats on the council, candidates ordinarily are virtually guaranteed election by the UN General Assembly.

Syria 101: 4 attributes of Assad's authoritarian regime

Syria said the switch had nothing to do with the continuing protests shaking the country. But the face-saving arrangement clearly came in response to the growing international controversy over repression in Syria that human-rights experts say has resulted in more than 700 deaths.

Some analysts of global institutions deemed Syria’s stand-down a sign the international community is demanding more rigorous human-rights standards.

“Yes, the US and other Western powers opposed Syria’s candidacy, but if the opposition had stopped there this probably would have gone through,” says Edward Luck, senior vice-president for research and programs at the International Peace Institute (IPI) in New York.

Saying opposition to Syria winning a seat on the council was growing in the General Assembly, he adds, “The larger point is that Syria was publicly campaigning for this, so it’s got to be embarrassing when it’s your peers saying you are not fit. It’s a significant slap in the face.”

Others counter, however, that Syria coming within a week of joining the world’s top human rights body hardly qualifies as progress.

“Do we really have to wait until a government is gunning down its own citizens in the streets before its membership on the council is deemed unacceptable?” says Steven Groves, an expert in international institutions at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

The fact the seat Syria wanted will now go to Kuwait is also no reason to declare great progress, Mr. Groves says. Kuwait will very likely vote just as Syria would have – in particular on issues relating to Israel – and if anything, Kuwait may have a worse record on women’s rights than the regime of Bashar al-Assad, he says.

The organization Human Rights Watch said Wednesday that Syria withdrew its candidacy rather than face “resounding defeat” in the General Assembly, which elects the Human Rights Council’s 47 members. The New York-based group noted that the council condemned Syria’s use of lethal violence against peaceful protesters in a vote April 29.

Think you know the Middle East? Take our geography quiz.

But Syria’s decision does not end a continuing debate over the way the council’s membership is elected, the organization says. Countries are candidates from regional groups that in all but a few cases have put forth slates of candidates equal to the number of seats up for a vote.

“States collude to avoid any competition in Human Rights Council elections, which benefits human rights abusers like Syria,” said Peggy Hicks, global advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, in a statement.

The group also called on Kuwait to take its near-certain accession to the council as an opportunity to improve human rights at home, in particular in the case of migrant and domestic workers.

After the Bush administration expressed its dissatisfaction with the Human Rights Council by refusing to join it, the Obama administration declared the US could do more good for international rights issues from the inside and now sits on the council.

The IPI’s Mr. Luck says it is undeniable that a “trend” is taking hold suggesting the international community is taking gross human rights violations – especially by governments against their own people – more seriously. He points to the Human Rights Council’s recent suspension of Libya from the council, and the General Assembly’s vote sustaining that suspension.

What’s needed next, he adds, is that countries with poor rights records not be considered as council candidates in the first place.

But others, like Heritage’s Groves, say the Human Rights Council remains a discredited institution because of who sits on it. The presence of a US or a Canada, he adds, won’t be enough to change it.

“As long as China and Cuba and Saudi Arabia and others from the rogues’ gallery are welcome, the US can stay on the council until doomsday and it’s not really going to change,” Groves says. “If it really is a human rights council, the very least would be to raise the bar for membership.”