Trump signals a US shift from 'soft power' to military might

Potentially leaving the UN Human Rights Council while boosting the Pentagon budget would point to a broader change in priorities.

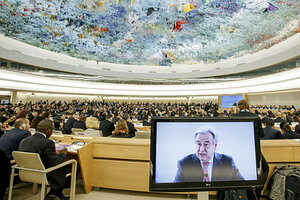

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres delivers his statement at the opening of the High-Level Segment of the 34th session of the Human Rights Council, at the European headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva, Monday, Feb. 27, 2017.

Salvatore Di Nolfi/Keystone via AP

The United Nations’ Human Rights Council opened its annual session in Geneva Monday amid chatter that the United States was weighing withdrawal from the world’s top rights watchdog body.

The US relationship with the council has long been problematic, in part over concerns that it focuses too much attention on alleged rights abuses in Israel while ignoring rogue states with far worse records.

Now reports have surfaced that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is questioning the council’s value to the US and considering a range of options – including simply pulling out. On Monday, a White House budget outline proposed as much as a 30 percent cut in State Department spending to help offset a $54 billion increase in military spending.

US spending on international organizations like the rights council is small change in the grand scheme of the US budget. Indeed the entire State Department budget –about $50 billion – is less than the increase Mr. Trump seeks for the Pentagon.

Taken together, some experts say, the potential withdrawal from the council and proposed State Department cuts represent a shift away from the increasing use of “soft power” to defuse or head off tensions overseas before they turn into conflicts.

“Trump seems to see US involvement in the world as a zero sum, so that increases in defense spending and the exercise of hard power mean pulling back from multilateralism and diplomacy,” says Melissa Labonte, an associate professor of political science and expert in international organizations at Fordham University in New York. “It’s a retreat from the idea that the constellation of interests of a global power like the US is best served by participation in an array of international organizations.”

Value of soft power

In recent years, soft power has been a crucial part of the US security toolkit as presidents have sought to make military intervention more of an option of last resort.

Under President Obama in 2013, for example, then-Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power went to the Central African Republic to help stop sectarian violence from turning into civil conflict during a tense election campaign. And over the past decade, USAID has initiated programs in drought-sensitive and conflict-prone pockets of Africa to help women farmers respond to food shortages that otherwise might have meant destabilizing family displacement.

Military leaders have underscored the essential contribution that investments in soft power make to US security. Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates’s close working relationship with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was well-known. And current Defense Secretary James Mattis told members of Congress in 2013, when he was commander of US Central Command, “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.”

On Monday, a group of more than 120 retired generals and admirals sent a letter with the same message to members of Congress, saying “now is not the time to retreat” on State Department and USAID spending. “We know from our service in uniform that many of the crises our nation faces do not have military solutions alone,” the group said, citing examples ranging from “confronting violent extremist groups like ISIS” to stabilizing weak states that, unaddressed, can lead to greater instability.

Are US interests served?

As the Trump administration reassesses US engagement overseas, the question revolving around the Human Rights Council is whether it is worth even the relatively small investment the US makes.

The Obama administration decided the US was better off influencing the global human rights agenda from inside the council, and stuck with it.

But some critics say the council’s track record is less than inspiring.

“The US probably has influenced council actions on the margins, but the real question we should be asking is whether it serves our national interests to remain a part of it,” says Brett Schaeffer, a fellow in international regulatory affairs at the Heritage Foundation in Washington. “Certainly we still see many of the same problems that people have been drawing attention to for a long time.”

Mr. Schaefer notes that the council replaced the earlier Human Rights Commission a decade ago after then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan said the commission’s failures were casting a shadow over the entire UN. But those failings have hardly been addressed, Shaefer says. It still allows some of the world’s worst rights abusers onto the commission, shies away from investigating the most egregious cases of rights abuse, all while demonstrating a bias against Israel.

“The impression you get is that the council is repeating the same mistakes that led Kofi Annan to call the commission a disgrace,” he says.

Shaefer says his recommendation to the Trump administration would be to either name a “firebrand” to represent the US at the council and forcefully call out its shortcomings – or withdraw from the council altogether.

How US has changed council

Others worry that withdrawal from the council would signal a broader US global retreat that would not serve US interests and would rattle allies who rely on robust US global participation.

“Even something like our participation in the Human Rights Council is not just about us but sends strong reassurances to our allies that we intend to be out there not just on security issues but defending the same values,” says Dr. Labonte.

In her view, the council offers evidence that strong US participation can lead international organizations to work better and to take steps that are in American interests.

“The US had a strong hand in bringing the council into the 21st century, and I think we see that in some significant improvements like the internal peer reviews, where countries hold each other accountable,” she says. The US has instigated investigations into countries, including Iran and Syria, that were either largely overlooked before or protected by larger powers, and has championed LGBT rights in the global forum, she adds.

Schaefer says US spending on the council is peanuts, but he notes that overall spending on international organizations (including activities like refugee assistance and international peace-keeping) has jumped by more than a third since 2010 to about $10 billion. “Any administration would be neglecting its responsibilities if it didn’t look at those contributions with a close eye,” he says.

Still, Schaefer says any cuts should reflect an assessment of what is working for the US. “I would hope the US would base its participation in the UN and its organizations on whether it is serving US national interests, rather than simply on a budget assessment,” he says.

For others, cutting the budgets that underpin US multilateral activities would be the embodiment of “penny wise, pound foolish.”

“The US contribution to multilateral institutions is already a rounding error in our defense budget,” Labonte says. “Spending more on the military and building up our nuclear arsenal” – two things Trump wants in a new budget – “should not come at the cost of global engagement that makes the need for military intervention less likely.”