Hosting Kenyan leader, Biden seeks to restore Africans’ trust in US

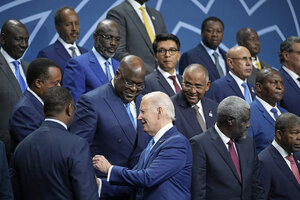

President Joe Biden talks with African leaders before they pose for a photo during the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, Dec. 15, 2022.

Andrew Harnik/AP/File

Washington

When President Joe Biden hosted 49 African leaders at a White House summit in December 2022, he pledged to make a trip to Africa in the coming year to showcase renewed interest and partnership after the Trump administration’s disregard for the continent.

The presidential trip would symbolize a U.S. commitment to a new kind of relationship with Africa – one based on furthering mutual security and economic interests while respecting African nations’ pursuit of independent paths, including deepening ties with other powers.

But the trip never happened. Instead, it symbolized what many Africans say is more of the same: an unreliable relationship of periodic fanfare over a promised new direction, with little follow-through.

Why We Wrote This

For years, the United States has faced setbacks to its standing and influence in Africa, losing out to China and Russia. A perennial African concern has been, will the U.S. deliver on what it promised? Hosting Kenya’s leader offers a path forward.

“The way that the Africans perceive the U.S. is that the U.S. promises a lot and does not deliver what it said it will deliver,” says Mvemba Phezo Dizolele, director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington. “So there’s a trust deficit.”

Mr. Biden will again try to jump-start U.S.-Africa relations – and reduce that trust gap – when he receives Kenyan President William Ruto for a state visit this week. It is the first state visit by an African leader since 2008, and the first by a Kenyan president in over two decades.

Ruto’s reputation

Mr. Ruto would appear in numerous ways to be the right choice to represent the path for Africa that the United States under Mr. Biden wants to encourage and cultivate.

Promoter of what he has dubbed a “hustler economy” that favors grassroots entrepreneurship and innovation over Africa’s more traditional reliance on business elites, the Kenyan leader is held up by many diplomats and regional experts for his stewardship of both a vibrant economy and a stable and advancing democracy.

“Ruto is quite popular in his own country; many Kenyans see him as dynamic and a break with the past,” says Phiwokuhle Mnyandu, assistant director of the Center for African Studies at Howard University in Washington. “At the same time, he seems to inspire that enthusiasm around the African continent.”

Indeed Kenya – viewed as a “middle power” when stacked against giants South Africa and Nigeria – has emerged as a new kind of leader in Africa, serving as a hub for humanitarian interventions across the continent, and increasingly on the international stage.

Kenya hosts U.S. special forces keeping an eye on Islamist extremists in neighboring Somalia, and recently accepted to take on – at U.S. encouragement – the tricky task of deploying what will be a United Nations-helmeted stability force to restore order to Haiti.

Kenya’s special forces police force, which has experience fighting East Africa’s Al Shabab extremist group, is set to arrive in Haiti within days.

“President Ruto is using this as an opportunity to raise his profile on the global stage,” says Cameron Hudson, senior fellow with the CSIS Africa Program. “Since coming to office he has really promoted himself internationally as a leader of the continent,” he adds, “hosting the African Climate Summit, his engagements at the U.N., his engagement around peacekeeping outside of Africa.”

Setbacks for U.S.

Yet at the same time, Mr. Ruto’s visit comes against a backdrop of setbacks for U.S. standing and influence in Africa.

U.S. troops are withdrawing from Niger after a decade of counterterrorism operations there. They were ordered out by the ruling military junta in favor of Russian soldiers from the Africa Corps – the new iteration of the mercenary organization formerly known as the Wagner Group.

Last month, military rulers in Chad also ordered U.S. troops stationed there to leave.

Elsewhere, Chinese investment and development deals have advanced, often in sensitive sectors like rare earth metals. A further sign of waning U.S. influence came last year when many African countries rebuffed U.S. diplomatic efforts to line up developing world support for Ukraine and global condemnation for Russia over its invasion of a neighboring country.

U.S. presidents going back to Bill Clinton have touted the idea of building trade and economic partnerships with Africa, but over the past decade, China has solidified its economic footprint on the continent. In recent years, China has been joined by smaller regional powers like Turkey and the Gulf states.

“Washington is learning late that it’s missing opportunities,” says Mr. Hudson. One of the “excuses” he says he has heard from U.S. officials for a long time is, “‘Well, we’re not China. We’re not a state-run economy. I can’t just tell Microsoft to go invest in Kenya [or] open a factory there.’”

While that may be, Mr. Hudson says that does not explain what has struck many as a roller coaster of initial attention to Africa followed by a step falling off.

The administration’s launch of a new Africa strategy in August 2022, followed a few months later by the leaders’ gathering in Washington, stoked fresh confidence that the Biden administration really was going to break the pattern of fanfare followed by neglect that has typified U.S.-Africa relations, he says.

“However, after that summit, we really saw a drop-off in at least presidential, if not high-level senior involvement from the administration,” he adds. “We have seen not the level of engagement that we would have expected from an administration that had launched this strategy and launched this summit.”

For their part, White House officials push back forcefully against any notion of administration neglect. They emphasize that an unprecedented number of Cabinet-level officials – 17 last year – have visited, as have first lady Jill Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

Howard University’s Dr. Mnyandu says there’s no denying the pattern of ups and down in U.S.-Africa relations – but he also says it can’t all be laid at the White House doorstep.

“Yes, there are ebbs and flows,” he says, “but sometimes it’s not the U.S. that is responsible, but the Africans themselves” who lack follow-through.

African exports

One item on President Ruto’s U.S. agenda that gives Dr. Mnyandu hope that this leader’s visit will be different is his planned stops at two Kenyan companies: Vivo Fashion in Atlanta and Wazawazi, which makes leather goods, in Denver.

“It wouldn’t be an eyebrow-raiser if it were the French president visiting French companies, but this augurs well for a new narrative about U.S.-Africa relations,” he says. “It says Africa isn’t always on the receiving end, but is now exporting to the U.S. and is a source of innovation.”

The expert on China-Africa relations says the way Mr. Ruto has organized his weeklong U.S. visit around business and investment opportunities, including with a dynamic diaspora, should also demonstrate to Americans a truth about most Africans: They would rather engage with the U.S. than with China if the opportunities are there.

“A typical African country realizes now that relations with the U.S. are going to be more comprehensive and people-to-people than [relations] with China,” Dr. Mnyandu says.

Even Chinese people tell him they know the typical African country relates better with the U.S. “because of this approaching each other as human beings,” he notes. “This is something that both sides should view with optimism.”