Boston bombing interrogation: Will prosecutors have a Miranda problem?

The government has cited public safety in its decision to question Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the alleged Boston Marathon bomber, for 16 hours before reading him his Miranda rights. Legal experts differ on whether that's OK.

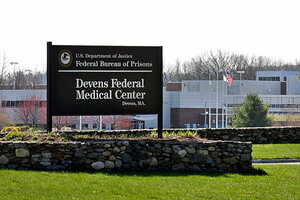

The US Marshals Service said Friday that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, charged in the Boston Marathon bombing, had been moved from a Boston hospital to the federal medical center at Devens, about 40 miles west of the city.

Elise Amendola/AP

New York

The Federal Bureau of Investigation questioned alleged Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev for 16 hours over two sessions without telling him he had the right to remain silent and to not implicate himself.

The FBI’s legal rationale for the long questioning period: It needed to find out if public security was at risk, perhaps because more bombs were planted or a collaborator was on the loose.

Was the government’s questioning excessive? And might it have some impact on the case?

Judging by the responses of some criminal defense lawyers, the government appears to be right on the line of what is permissible under the law – in terms of the amount of time involved and possibly the type of questions asked.

However, it’s hard to know how long it will take to get information that may be necessary to protect the public, former prosecutors say.

“It does not seem unreasonable to question Tsarnaev for that period of time,” says Thomas Dupree, a former deputy assistant attorney general and now a partner in Washington law firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. “Public safety is paramount here. Law enforcement has to have time to ask questions.”

But 16 hours of questioning seems excessive to Tamar Birckhead, a former federal public defender in Massachusetts and now an associate professor of law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“In the past, it was interpreted as five minutes. Then 50 minutes was found to be fine,” Ms. Birckhead says. “But 16 hours definitely seems beyond the pale.”

Both sides acknowledge that the so-called public safety exception is vague.

The issue goes back to 1980 when police in the Queens borough of New York received a call that a woman said she had been raped and the suspect was in a supermarket carrying a gun. A police officer ended up apprehending a suspect who had an empty shoulder holster.

After the police officer handcuffed the suspect, he asked him where the gun was. The suspect nodded toward some cartons. The officer retrieved the gun, formally arrested him, and read the man his Miranda rights. The man said that he would answer questions without an attorney present and that he owned the gun.

The trial court excluded the statement and the gun as well as his other statements because of the Miranda violation. This was affirmed by an appeals court. But in 1984, the US Supreme Court overturned the lower courts and said that in this case, public safety (finding the gun) was more important than the Miranda warning.

In recent years, the Justice Department seems to have decided to expand the public-safety exception to include other types of intelligence, Birckhead says.

She cites a 2010 DOJ memorandum to the FBI obtained by The New York Times, which stated that after all public-safety questions may have been asked, “agents nonetheless conclude that continued unwarned interrogation is necessary to collect valuable and timely intelligence not related to immediate threat, and that the government’s interest in obtaining this intelligence outweighs the disadvantages of proceeding with unwarned interrogation.”

How that intelligence gets used is also open to question.

For example on Thursday, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said that during the interrogation of Mr. Tsarnaev, he indicated he and his brother Tamerlan, who was killed, had planned to go to New York to set off bombs in Times Square.

Both officials appeared to be talking about possible evidence in the case, obtained without the suspect receiving a Miranda warning.

“There are limits on what you can say,” says defense attorney Joshua Dratel of Dratel & Mysliwiec in New York, speaking about Mayor Bloomberg and Kelly’s press conference. “They are not supposed to talk about this, so it’s already a major problem,” Mr. Dratel says.

If the information that the FBI received is “intelligence,” asks Dratel, who is a leading terrorism defense lawyer, “Why is it bandied about in public?”

One argument for not reading Tsarnaev his Miranda rights is that the government might never get important information about future attacks.

But now that Tsarnaev has been read his rights, it doesn’t mean that he won’t eventually cooperate with the government, Birckhead says. A large percentage of those charged with crimes tend to cooperate with the government in return for the possibility of a lesser sentence, she says.

“It could be that months ahead, Dzhokhar and Miriam Conrad [a federal public defender and his lead defense counsel] conclude it makes sense to sit down with the prosecutor,” she says, in return for the prosecutor taking the death penalty or even life in prison without parole off the table.

Birckhead thinks one reason the FBI decided to question Tsarnaev for 16 hours could have been to establish precedent – so the next time a terrorism suspect is arrested, they can also be questioned at length.

“I would imagine someone involved in the prosecution and investigation is thinking ahead,” she says. “Lawyers do that: They are always asking, ‘Are we setting precedent down the line?’ ”

Dratel says that possibility is chilling to him. “It is letting the genie out of the bottle,” he says. “It fills criminal defense lawyers with dread.”

• Staff librarian Leigh Montgomery contributed to this report from Boston.