With Nidal Hasan bombshell, time to call Fort Hood shooting a terror attack?

Maj. Nidal Hasan, the Army major facing court-martial for a mass shooting at Fort Hood in 2009, plans to argue that he acted in defense of the Taliban in Afghanistan. So much for the official US line that the shootings were an act of workplace violence, critics say.

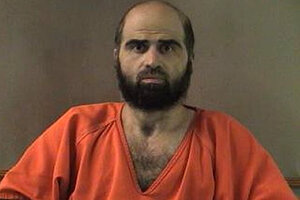

This undated file photo shows Nidal Hasan, the Army psychiatrist charged in the deadly 2009 Fort Hood shooting. On Monday, Judge Col. Tara Osborn ruled that Hasan could fire his attorneys and defend himself, after deeming him sound enough in mind and body to represent himself in court.

Bell County Sheriff's Department/AP

The admission by Army Maj. Nidal Hasan on Tuesday that he attacked Fort Hood in 2009 in defense of “the leadership of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the Taliban” has suddenly undermined the Obama administration’s previous contention that the murders of 13 soldiers at the Texas base constituted an act of “workplace violence.”

Hasan’s legal argument, which is being considered by the judge, Col. Tara Osborn, may reignite the political furor over how the Obama administration has classified the shootings, as well as arguments about whether the mass shootings constituted the first major Islamic jihadist attack on the US after 9/11. As recently as May 23, President Obama said no "large-scale" terrorism attacks on the homeland have occurred on his watch.

Officials at the US Department of Defense have said there isn't enough evidence to put Hasan on trial for an act of terrorism, and they have worried that such a claim could undermine the Army major's right to a fair trial.

Critics argue that the Fort Hood incident has not been characterized as a jihadist attack in part to give the Obama administration political and policy cover. Moreover, they add, the Obama position works to the detriment of shooting victims, which includes the 32 wounded and the families of those killed. Victims would have been eligible for combat compensation under US law if the Pentagon had classified Hasan not as a murderous US Army psychiatrist but rather as an enemy combatant or an “associated force” under the Military Commissions Act of 2006, they say.

“If you were an apologist for Hasan, you can no longer advance the false narrative that he’s a disgruntled employee,” says Jeffrey Addicott, director of the Center for Terrorism Law in San Antonio, Texas. “He has now labeled himself as a jihadist Islamist murderer, a hardcore jihadist. It’s now clear…, in spite of our leadership in this country, including the Department of Defense and Obama, what his motives are.”

Osborn, the court-martial judge, is set to decide Wednesday whether to allow Hasan another three months to expand on his “defense of others” argument. The basic reasoning is that he attacked the soldier readiness center on Nov. 5, 2009, because soldiers there were about to be deployed to Afghanistan on a mission to kill Taliban.

Legal experts say it will be tough for Hasan to prevail using that argument, because he won't be able to prove that those soldiers who were shot posed an imminent or direct threat to individual Taliban leaders.

On Monday, Osborn ruled that Hasan could fire his attorneys and defend himself, after deeming him sound enough in mind and body to represent himself in court.

US military law experts said this week that Osborn will have to control the trial “moment to moment” to keep Hasan’s cross-examinations and arguments to the facts at hand, but that it will be impossible to prevent him from making jihadist rants or from using the courtroom as a pulpit to promote jihad.

Despite military judges’ latitude to keep outbursts to a minimum, the system is not equipped to prevent “someone from using it as a platform,” Aitan Goelman, a former Department of Justice terrorism prosecutor, told the Monitor on Tuesday. It gives defendants “a certain amount of latitude to use the system for their own ends.”

Hasan’s decision to align himself with the Taliban in his defense may, in some eyes, counter the president's recent statements about the conduct of the war on terrorism – especially whether it's time to bring the so-called global war on terror to a close and whether he should assert that no big attacks on the US have occurred during his tenure.

In a major national security speech on May 23, just over a month after the April 15 bombing of the Boston Marathon, Mr. Obama credited his administration for “[changing] the course” of the war against Al Qaeda. “We ended the war in Iraq and brought nearly 150,000 troops home,” the president said. “We unequivocally banned torture, affirmed our commitment to civilian courts, worked to align our policies with the rule of law. … There have been no large-scale attacks on the United States, and our homeland is more secure.”

He did, however, also address the Fort Hood shooting directly, acknowledging that it was an act "inspired by larger notions of violent jihad."

The hair-splitting question thus becomes, was Hasan an alienated American "inspired" by jihad, or was he an actual jihadist? Obama appears to take the former view, while others see in Hasan's defense strategy an admission of the latter.

More immediately, lawyers for the victims say Hasan’s statement confirms that soldiers who were killed or wounded during the shooting deserve a different kind of treatment.

“We call on the Army to … admit that the Fort Hood attack was terrorism, and finally provide the Fort Hood victims, survivors, and families with all available combat-related benefits, decorations, and recognition,” said Neal Sher and Reed Rubinstein, the victims’ lawyers, according to ABC News.