Conviction of ex-mayor Ray Nagin: Does it signal new era for New Orleans?

Ray Nagin was convicted Wednesday of 20 federal corruption charges, many connected to recovery efforts after hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. He could face more than 20 years in prison.

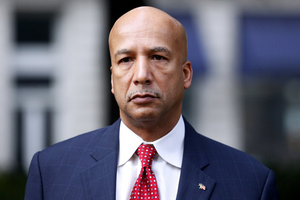

Former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin arrives at the Hale Boggs Federal Building in New Orleans, January 27.

Jonathan Bachman/AP/File

Ray Nagin, the two-term mayor of New Orleans who became the face of indignation following the failed federal response after hurricane Katrina, was convicted Wednesday of 20 federal corruption charges.

According to the federal government, Mr. Nagin, who left office in 2010, accepted thousands of dollars in bribery money, among other gifts, from contractors and vendors that swarmed New Orleans after Katrina, hoping to take part in the huge recovery effort. Some of the corruption charges, however, deal with issues predating the 2005 catastrophe.

Sentencing is set June 11. Under federal sentencing guidelines, Nagin faces more than 20 years in prison.

Walking outside the federal courthouse in New Orleans, Nagin could be heard saying, “I maintain my innocence.”

The case against the former mayor was towering. In the nine-day trial, prosecutors summoned many co-conspirators to the stand who testified to the pay-to-play schemes Nagin orchestrated, plus the bribes worth hundreds of thousands of dollars that he sought and then redirected to Stone Age, a granite countertop business operated by his sons, who were not charged.

In addition to the witnesses, prosecutors presented jurors with a mountain of evidence – e-mail correspondence, business contracts, credit card and bank statements, and more – that they said proved the mayor was a willing participant in wielding power for personal profit.

Nagin was convicted on five counts of bribery, nine counts of wire fraud, one count of money laundering conspiracy, four counts of filing false tax returns, and one overarching count of conspiracy. Jurors acquitted Nagin of a single charge of bribery related to a $10,000 bribe that prosecutors said he accepted through the family business.

“The physical evidence was so overwhelming that for Ray Nagin to have successfully defended this case, he would have had, in some way, to refute these documents and use his credibility,” says Michael Sherman, a political scientist at Tulane University in New Orleans and a former legal adviser to current mayor Mitch Landrieu.

That proved difficult. His defense team argued that prosecutors overreached in connecting the dots between the documents and supposed wrongdoing, but Nagin’s own testimony in the trial became his side’s worst enemy. Among his explanations: He was not aware that business associates picked up the tab for vacations to Hawaii, Jamaica, and New York City.

Mr. Sherman says the moment in the trial that became irreversible for Nagin was last week when he admitted to putting Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day and wedding anniversary dinners on the city credit card, but said he reimbursed the city. Those records were never produced.

“He revealed in that one moment that this was not a lapse of judgment but was his base line of what was acceptable and what was not. He was so off base, he lost all credibility needed to confront the allegation,” Sherman says.

The conviction represents a big downfall for Nagin, a former executive of a statewide cable company who campaigned as a reformer and was backed by a biracial coalition of support. He entered the international spotlight after channeling the outrage that most New Orleans residents felt in the immediate wake of Katrina, after media images of people stranded atop houses and outside the city convention center suggested that the federal government was incapable of fulfilling basic needs like bottled water and transportation for area citizens.

After half the city’s population relocated to other states, particularly to Texas, Nagin became a voice for black unity. On Martin Luther King Day in 2006, he expressed fear that New Orleans would lose its “chocolate city” status if black voters did not return to support his reelection. The strategy worked, and Nagin won election that year, beating Mr. Landrieu.

Recovery under Nagin slowed, and he failed to achieve the majority of goals he outlined to bring the city back. When charges were leveled against him in January 2013, it was revealed that he was under a federal probe during the post-Katrina period.

“He got a lot of goodwill after Katrina, but what enraged people during this scandal was his failure to act and accomplish things,” says Tania Tetlow, a former federal prosecutor who is now a law professor at Tulane. The trial ultimately revealed the contrast between “the black hole of the mayor’s desk in getting anything done for the city and how hard he worked for contractors who were paying him at the side,” she says.

Advocates for the city – saying that an upswing in economic development, a rebound in population, and the revitalization of neighborhoods characterize the new New Orleans – are framing Wednesday’s verdict as a break from the past regime. Nagin is the first mayor of New Orleans for whom federal prosecutors have successfully obtained a conviction for crimes committed while in office.

The current mayor, Landrieu, told reporters late Wednesday it is “important” that people know the city “has been in different hands [over] the past four years” and is “making great progress, and we like the new way.”

Landrieu was reelected to a second term earlier this month.

The verdict represents “a sign of things changing and that the community is just not putting up with this anymore,” says Ms. Tetlow. “What we’re seeing is a flurry of convictions as the community cleans house.”

Two associates who testified against Nagin are both awaiting sentencing in the bribery schemes.