Dunn 'loud music' verdict: Does 'stand your ground' ask the impossible?

The judge in the 'loud music' killing trial of Michael Dunn included 'stand your ground' in his jury instructions. The law asks juries to try to tease out the defendant’s real emotions and motivations.

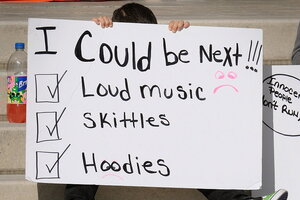

Jacob Black ducks his head behind the sign he holds outside the Duval County Courthouse, Feb. 15, in Jacksonville, Fla. Michael Dunn was convicted on the same day of attempted murder for shooting at several teens during an argument over loud music, but jurors could not agree on the most serious charge of first-degree murder, for the death of Jordan Davis.

Kelly Jordan/The Florida Times-Union/AP

Atlanta

The Michael Dunn verdict on Saturday – in which the white, 47-year-old software engineer was found guilty on attempted murder charges, but not on a first-degree murder charge for killing a 17-year-old black youth, Jordan Davis of Atlanta – has once again put the issue of armed self-defense firmly in society’s crosshairs.

The hung jury on the main murder charge came seven months after George Zimmerman, a half-Caucasian, half-Hispanic neighborhood watch captain, was found not guilty in a murder trial for killing Trayvon Martin, another black 17-year-old who, like, Jordan Davis, was not armed.

The nonverdict on the murder charge in Mr. Dunn’s case – prosecutors vow to retry him – is tempered by guilty verdicts for three counts of attempted murder after he peppered a fleeing SUV and its four occupants with 10 9-mm bullets, nine of which struck the vehicle. He could face from 15 to 60 years in prison for those crimes. His attorney says he’ll appeal.

The overriding question after the verdict is what role so-called stand-your-ground laws – now in force in at least 20 states – play in the decisions by police, prosecutors, judges, and juries, especially when considering cases that have racial overtones.

The issue is intensified by the explosive growth in the numbers of Americans carrying concealed weapons in public, from 1 million in the mid-1990s to at least 8 million today.

Mr. Zimmerman referred to Trayvon Martin as a “punk,” and Dunn blamed “thug culture” for the shooting, which followed an argument over loud music. Many Americans, including the parents of the slain teens, see those terms as codes for racial prejudice, especially against black youths.

In both cases, adult men decided to engage black teenagers whom they said they feared, and then, after emotions rose, decided to fire. In Zimmerman’s case, evidence showed he had taken punches from Trayvon; in Dunn’s case, only angry words, no fists, flew over a disagreement over what Dunn called overly loud “rap crap” music coming out of Davis’s SUV outside a Jacksonville convenience store.

Stand-your-ground laws, pioneered in Florida in 2005, extend the so-called castle doctrine – a notion of English common law – from the home to public places. The basic idea is that citizens have no “duty to retreat” from an aggressor before using deadly force to stop an attack if they have reasonable suspicion that they’ll be hurt or killed.

On CNN, legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin said the issue is as much political as legal, because the laws are largely supported and passed by Republicans, and largely chided by Democrats.

The Dunn case, to many observers, reaffirms a central finding of a Texas A&M study released in 2012 – that stand-your-ground laws have begun to change the public calculus of self-defense in the United States.

For one thing, the Texas A&M study found that justifiable homicide findings rose by 8 percent, on average, in stand-your-ground states. Another study, by the Urban Institute, found that black shooters have a harder time arguing justifiable homicide than whites if they’ve killed or hurt someone of a different race, which suggests a bottom line “where it’s really easy for juries to accept that whites had to defend themselves against persons of color,” Darren Hutchinson, a civil rights law expert at the University of Florida, told the Monitor last summer.

Stand-your-ground proponents, however, note that some of the biggest defenders of the law are defense attorneys, since black defendants have a higher success rate than whites do in invoking the law. Most such cases in Florida, however, involve black-on-black violence in which an armed attacker is rebuffed with gunfire.

The Jacksonville jury in the Dunn case took four days to negotiate the final verdict, a testament to one of the main tentacles of criticism: that the new law, largely supported by gun lobbies to make gun use more defensible, can be confusing in its application.

To that point, it's notable that the state's actual stand-your-ground law was not invoked by defense attorneys in either the Zimmerman or Dunn cases, but that both judges referred to the law in their jury instructions.

The law forces juries to try to do what many would deem impossible: tease out the defendant’s real emotions and motivations, given that the adversary has often been permanently silenced.

“Self-defense cases have to be the toughest for jurors to deliberate because the difference between murder and self-defense depends on what the defendant felt in his heart,” Florida defense attorney Mark O’Mara, who successfully defended Zimmerman, writes about the Dunn case. “At some levels, we burdened the jury with an impossible task, and they knew if they got it wrong, they’d either be sending an innocent man to jail or letting a murderer go free. In this case, no verdict may very well have been the most appropriate decision."

That argument highlights what can happen when lawmakers look for solutions to a nonexistent problem. The Florida law, for example, was a conservative reaction to a post-hurricane Andrew incident in which a homeowner was charged by prosecutors after killing an intruder in the mayhem after the storm.

"This trial is indicative of how much of a problem stand-your-ground laws really do create,” Anne Franks, a law professor at the University of Miami, tells The New York Times. “By the time you have an incident like this and ask a jury to look at the facts, it’s difficult to re-create the situation and determine the reasonableness of a defendant’s fear.”

Some commentators saw in the verdict a continuation in a slow national march toward greater rights for gun owners, and fewer rights for the unarmed, especially minorities.

“The verdict came days after the Ninth US District Court of Appeals struck down California's limits on concealed weapons as overly restrictive in violation of the Second Amendment,” the San Francisco Chronicle opined on Sunday. “There can be no better example of how that law [limiting concealed weapons] is a needed check against the presence of guns in life's moments of irrationality.”