'Historic' drop in federal inmates comes as left and right find common ground

US Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the federal prison population dropped after decades of increases. Both conservatives and liberals are 'coming together on these issues.'

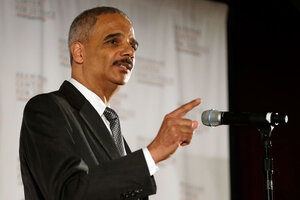

US Attorney General Eric Holder delivers a keynote speech at New York University's law school Tuesday in New York. He said the federal prison population has dropped in the last year by roughly 4,800.

Julio Cortez/AP

New federal and state policies that treat lawbreakers with a lighter touch have resulted in a “historic” drop in the US prison population, United States Attorney General Eric Holder announced Tuesday.

Perhaps just as surprising, many conservative politicians who have often looked upon Mr. Holder as their nemesis basically agree with him.

The number of federal inmates has fallen by 4,800 since last year to a total of 215,000 – the first time the federal prison population has registered an annual decline since 1980, according to The Washington Post. Holder wants to reduce the number a further 10,000 by 2016, which would be enough to leave six maximum security prisons empty.

His package of policing and justice reforms is designed to divert nonviolent criminals away from prison and is seen as a rebuke of the so-called 1994 “crime bill,” which expanded the list of felony crimes, pumped $10 billion into new prisons, and gave incentives to states to mass incarcerate even low level offenders.

Meanwhile, states including Texas, Georgia, and Pennsylvania, have taken similar steps, spurred to action by their large prison populations. The result is a broader shift in America's approach to justice, in which both conservatives and liberals are finding significant common ground.

“This is nothing less than historic,” Holder told a New York City audience. “My hope is that we’re witnessing the start of a trend that will only accelerate.”

Holder noted that policing and justice reform is being hotly debated around the country, and that the US has the chance to “rise to the historic challenge and critical opportunity that is now right before us.”

Some experts largely agree with Holder's assessment.

“It is a historic moment to see this change in philosophy and to see the right and the left coming together on these issues, and to recognize that we need more effective approaches to public safety,” says Michelle Deitch, an incarceration expert and professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin. “I’d point out, though, that it’s a very big ship to turn around.”

The trend is born of a dark flipside: The US, with 5 percent of the global population, now houses 25 percent of the world’s inmates, the majority of whom are incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses.

Historically, conservatives have pointed to dropping crime rates during the past 20 years as evidence of the effectiveness of the take-lots-of-prisoners laws ushered in during the Reagan presidency and formalized in the 1994 crime bill. But experts say the relationship between prison populations and crime rates is a tenuous one.

Research shows that the prison population growth has only had a marginal impact on the dropping crime rate, says Professor Deitch. This realization has come as the public has more broadly begun to acknowledge that over-policing and over-incarcerating means the US is “pouring billions of dollars into prison systems around the country, with not that much payback,” she adds.

For example, Texas, Georgia, and Pennsylvania have cut billions of dollars in prison costs during the past few years while overall crime rates have stayed level.

Several factors are at play in the dip in the federal prison population, which came even as state prison populations jumped by 6,000 after four straight years of steady decline. One reason is Holder’s orders to US attorneys to divert nonviolent offenders away from long mandatory minimum sentences. Another factor is the Fair Sentencing Act, passed four years ago, which adjusted a controversial disparity in sentencing between crack and powder cocaine – a disparity that had an outsize impact on young black men.

In his speech Tuesday, Holder also invoked the unrest in Ferguson, Mo., as an opportunity to more deeply address policing problems like “implicit bias” against minorities.

Many conservative Americans disagree with that assessment, saying the events in Ferguson amounted to more a breakdown of law and order than a legitimate protest against racial injustice. And in a February editorial, the conservative Washington Times criticized Holder for his initiative to make it easier for ex-convicts to vote, saying the attorney general “courts the cell block vote.”

Given such antagonism, it’s notable that Holder’s justice reforms have such wide-ranging bipartisan support. The main reason is that it’s conservative “red” states, which often have the largest per capita prison populations, that are wrestling with these issues.

Case in point: Holder and Texas Gov. Rick Perry sometimes seem like sworn enemies given the Justice Department’s intervention on environmental laws and the state’s voter ID efforts. But Texas, the state with the biggest prison system, has implemented reforms including a 2007 "justice reinvestment" law that saved taxpayers $2 billion by introducing softer sanctions and prison-diversion programs for nonviolent offenders.

Citing the success of such efforts, Holder said Tuesday: “It’s no longer adequate, or appropriate, to rely on outdated models that prize only enforcement, as quantified by numbers of prosecutions, convictions and lengthy sentences, rather than taking a holistic view.”