When expert testimony isn't: Tainted evidence wreaks havoc in courts, lives

Across the country, the criminal justice system is grappling with the fallout from decades of faulty analysis in criminal cases that may have resulted in thousands of wrongful convictions.

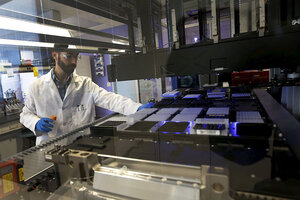

Technician Matthew Smith loads a robotic DNA sample automation machine at a pharmaceutical laboratory in Tarrytown, New York. A 2009 study of 156 innocent people convicted of serious crimes who were later exonerated by DNA evidence found that 60 percent of the forensic analysts called by the prosecution provided invalid testimony.

Mike Segar/Reuters

Boston

Kevin Bridgeman has been out of prison for almost three years, but it’s possible that he never should have been in there in the first place.

A lab chemist is serving three years for falsifying forensics in Mr. Bridgeman’s case and up to 40,000 other defendants. The chemist is already two years into her sentence, but Massachusetts’ highest court has just now determined how to deal with the backlog. This case, while egregious, is not the only example of faulty forensics – although it is usually an instance of bad science, rather than a bad scientist, experts say. From microscopic hair analysis to fingerprinting, forensics that are treated as gospel in the courtroom have been proven to be anything but foolproof.

Across the country, the criminal justice system is grappling with the fallout from decades of faulty analysis in criminal cases that may have resulted in thousands of wrongful convictions.

In Bridgeman’s case, in separate incidents in 2005 and 2007, police alleged that he sold a substance resembling crack cocaine to undercover officers. He pleaded guilty in exchange for the prosecution downgrading or dismissing some of the charges against him. In total, he served six years for both offenses.

However, what neither Bridgeman nor the police knew was that one of the chemists at the Hinton Lab in Massachusetts was simply eyeballing alleged drug samples, rather than testing them. In what some have called one of the most egregious example of tainted forensics in the United States, Annie Dookhan is now serving a three-year prison sentence for charges including having provided false testimony and altering test results to manufacture positive results.

Bridgeman, for his part, spends his days volunteering for a nonprofit that helps other former inmates. He hasn’t sought to withdraw his guilty plea or have his conviction vacated. Neither have thousands of other defendants, either because they were afraid they would face harsher charges, like Bridgeman, or because they simply didn’t know they could.

The human cost can be severe, even for those, like Bridgeman, who have been released from prison, says Matthew Segal, legal director for the ACLU of Massachusetts, which filed the petition on behalf of Bridgeman with law firm Foley Hoag. Convictions can make it difficult for a person to get a job, housing, even a driver’s license.

“We’re talking about people who are already not in prison anymore, and they’re dealing with crippling collateral consequences of being convicted,” says Mr. Segal. “They want to move on with their lives and these tainted convictions can get in the way of that.”

A state-ordered review in 2013 found that more than 40,000 cases could have been affected by Ms. Dookhan’s misconduct. Lawyers for the state prosecutors say the number was likely closer to 20,000. By the end of 2014, only 1,187 defendants had filed for post-conviction relief, according to court papers.

“A lot of defendants didn’t know how to find the courthouse,” says Segal, “and many other defendants were too afraid to knock on the courthouse doors.”

Last week, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in a case – in which Bridgeman was the lead petitioner – that Dookhan defendants can only be re-prosecuted under the terms of their original plea agreements. They will not face harsher penalties if they seek to clear their names.

“Courts have not yet heard from a lot of these defendants,” says Segal. “That’s why we think this ruling from Monday is such a landmark victory.”

High-profile examples of forensic evidence being less clear-cut than is typically portrayed on “C.S.I.” have littered the headlines in recent years. Perhaps the most significant is last month’s admission by the FBI that, after reviewing 500 cases that employed microscopic hair analysis, examiners’ testimony contained erroneous statements in at least 90 percent of the cases.

Defendants in at least 32 of those cases received the death penalty, according to the FBI. Nine of those defendants already have been executed, and five died of other causes while on death row.

The review is part of an ongoing, long-term investigation of decades of FBI microscopic hair analysis the agency is conducting in partnership with the Department of Justice, the Innocence Project, and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. The project launched in July 2013, and last month’s announcement covered the first 500 cases of an estimated 3,000 spanning from the 1970s up to 2000.

Brandon Garrett, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, said that forensic disciplines like microscopic hair analysis are, at the most, useful “as a tool to exclude” suspects, not a tool to specifically identify them. But they are rarely treated that way by forensic scientists.

“Analysts often seem to do something more ambitious – identify particular people – and that is more than many of these techniques can currently accomplish,” wrote Professor Garrett in an e-mail.

The subjective nature of forensic science has been public knowledge for some time. A report from the National Academy of Sciences in 2009 found that microscopic hair analysis – along with other juror-trusted forensic techniques like bite-mark, ballistics, and even fingerprint analysis – were unscientific in their methodology.

The trust juries put in forensic evidence is part of the problem, experts say.

Garrett published a study in 2009, which studied the trial transcripts of 156 innocent people convicted of serious crimes who were later exonerated by DNA evidence. The study found that 60 percent of the forensic analysts called by the prosecution provided invalid testimony, “with conclusions misstating empirical data or wholly unsupported by empirical data.”

The study noted “the adversarial [judicial] process largely failed to police this invalid testimony.” Defense attorneys rarely cross-examined these analysts, the study added, and rarely obtained experts of their own. Judges seldom provided relief.

Peter Neufeld, co-founder and co-director of the Innocence Project, says that it shouldn’t be the judge’s responsibility to provide the relief.

“The courts are the wrong place, the wrong venue to get it right,” says Mr. Neufeld, who was a co-author on Garrett’s 2009 study. “Defense lawyers, prosecutors, and even juries by and large, are scientifically illiterate.”

While many lawyers, judges, and juries may not be able to distinguish credible forensic testimony from the erroneous, the weight it can have over the ultimate verdict is immense.

Convicted by a hair

Taxi driver John McCormick was fatally shot on the doorstep of his house in Southeast Washington, D.C., in the middle of a summer night in 1978. Santae Tribble, 17 at the time, insisted during his three-day trial that he had been asleep at home at the time of McCormick’s murder, according to The Washington Post. His brother, girlfriend, and a house guest all testified to the same.

The jury deliberated for two hours, then asked about a stocking mask found in an alley a block away from McCormick’s home. The mask had been recovered by a police dog, and contained 13 hair fibers. An FBI analyst testified that one of the hairs from the mask matched Tribble’s “in all microscopic characteristics.” The prosecution also said in closing there was perhaps “one chance in ten million” that the hair could have belonged to someone else.

Mr. Tribble was found guilty of murder and sentenced to 20 years to life in prison. He served 25 years before he was released, and then spent three years in jail for failing to meet the conditions of his parole. In 2012, he was successfully exonerated by DNA testing. The testing also found that one of the hairs identified by the FBI as human belonged to a dog.

A juror in the case, Anita Woodruff, told the Post in 2012 that she had been “haunted” by suspicions about the conviction.

“The main evidence was the hair in the stocking cap,” she told the Post. “That’s what the jury based everything on. How else could his hair get in there unless he had the stocking cap on?”

Fix forensics before it gets to court

With forensic evidence holding such sway over jurors, those working to improve the system are calling for “upstream” fixes. In other words, if jurors can’t distinguish good science from bad science, the science needs to be good before it gets to court.

This is especially important since most criminal cases never see a courtroom in the first place. More than 90 percent of state and federal cases end in plea bargains, where forensic evidence is only presented in a report signed by the primary analyst.

Garrett says the lack of cases that actually reach a courtroom limits how much pressure judges could exert to help speed up the process of fixing forensic science and crime labs at the state and federal level.

“Judges really could trigger change, but so few cases come before judges, so it is equally important or more so that labs use sound methods in the first instance,” says Garrett.

Garrett and Neufeld wrote in their 2009 study that the scientific community can, “through an official government entity,” create and disseminate scientific standards to ensure the valid presentation of forensic science in criminal cases. The NAS study from the same year recommended the same thing, adding that the agency should not be part of the Department of Justice or any other law enforcement agency.

In 2013, Congress established the National Commission on Forensic Science in partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology – a wing of the Department of Commerce – to establish and enforce uniform best practices for forensic scientists and laboratories. Neufeld, who is on the Commission, added that the American Association for the Advancement of Science is also analyzing peer-reviewed literature on the disciplines, looking for “gaps” in the research that need to be filled in by further study.

“Those are big changes,” says Neufeld. “It’s the federal government really becoming involved in establishing major changes that will impact forensic science across the country.”

He described the efforts as an attempt to bring the public accountability in forensic science to the level it has achieved with clinical science, where drugs and other products go through rigorous independent analysis before they reach pharmacy shelves.

“There is no similar structure to protect the public from shoddy products or shoddy forensic scientists in forensic science,” he says.

Experts have commended the FBI for both admitting its errors and informing prosecutors, defendants, and defense lawyers in a timely fashion. But reviewing this many cases is almost unprecedented. The Dookhan scandal showed, at the state level, how the judicial system can be ill-equipped to handle major forensic scandals, which makes defendants wait even longer for justice.

A Texas crime lab experienced a similar scandal last year, when a Houston Police crime lab technician resigned after an internal investigation found evidence of lying, improper procedure and tampering with an official record, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Segal, from the ACLU of Massachusetts, says that within months, Texas investigators had a list of every single piece of evidence that the technician had ever touched.

That hasn’t been possible in the response to the Dookhan case, he adds.

“The management and record keeping at [the Hinton Lab] were ridiculously poor,” says Segal. “It’s not just that Annie Dookhan committed misconduct, but that she did it in a lab and in a justice system that were ill-prepared to handle the problem.”

Segal says that improving the independence and quality assurance process at state labs would not only make misconduct or basic scientific errors less likely at crime labs, but if those things did occur, the subsequent investigation would be faster and more efficient.

“It would make misconduct happen less often, and if it does happen a reporting procedure would be in place,” he adds. “Disclosure would be automatic.”

Many state crime labs also have close relationships with law enforcement. A 2013 study found that statutes in some states – including Florida and North Carolina – mandate that judges provide labs with remuneration “upon conviction,” and only upon conviction.

Re-opening cases tainted by misconduct (as in Dookhan’s case), or simply bad science (as in the FBI cases), isn’t going to happen to overnight, says Norman Reimer, executive director of the NACDL. Each tainted conviction is different, both in terms of how incorrect the forensic evidence presented was, and how influential it was in the sentence handed down. Most cases aren’t as clear-cut as Bridgeman’s or Tribble’s.

“There definitely will be some people that were wrongfully convicted,” says Mr. Reimer.

But what every affected defendant was deprived of, he says, is “a fair determination by a jury.”

“But it has to be done on a case by case basis,” he adds, “and that’s very difficult.”