Why #IStandWithAhmed is about more than a Muslim boy in Texas

Juvenile arrests often create a stigma around a student that leads to further delinquent activity. Ahmed Mohamed, a 14-year-old in Texas, has been flooded with support that may soften the blow, experts say.

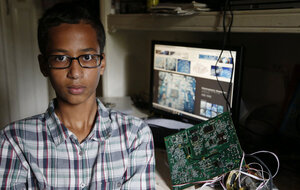

Irving MacArthur High School student Ahmed Mohamed, 14, poses for a photo at his home in Irving, Texas on Tuesday. Mohamed was arrested and interrogated by Irving Police officers on Monday after bringing a homemade clock to school. Police don't believe the device is dangerous, but say it could be mistaken for a fake explosive. He was suspended from school for three days, but he has not been charged.

Vernon Bryant/The Dallas Morning News/AP

Less than a day after news broke that a 14-year-old Muslim boy had been arrested for having a homemade alarm clock that was mistaken for a bomb, expressions of support began flowing in from within his community, around the country, and even from the White House.

Given the potentially life-changing consequences from even a brief interaction with the juvenile justice system, the show of solidarity for Ahmed Mohamed may offer real help for the teen and his family.

“Social support and community support – those can offset risk,” says Shawn Marsh, chief program officer for juvenile law at the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Children in the juvenile justice system, he adds, “experience a massive amount of risk. With the right protective factors they can get support and develop robustness.”

The incident began about 20 minutes before bedtime on Sunday, when Ahmed assembled the clock for homework, The Dallas Morning News reported. After a teacher at his Irving, Texas, school raised the suspicion that it looked like a bomb, he found himself pulled out of class and in a room with the school principal and five police officers.

“They interrogated me and searched through my stuff,” he said in an interview with the Morning News.

Ahmed was then escorted from the school in handcuffs, an officer on each arm, and taken to a juvenile detention center. He had his fingerprints and mug shot taken. His parents arrived to pick him up before he saw the inside of a jail cell.

He said the experience “made me feel like I wasn’t human.”

While he wasn’t incarcerated – and will not face charges, the Irving Police Department announced Wednesday – just getting arrested and processed can have negative effects on a young student. Being escorted out of school in handcuffs has its own consequences, according to Mr. Marsh.

“He’s experienced the stigma, the shame, of being arrested, paraded out of school,” he says. The effects of this so-called perp walk can be harsher for teenagers, he adds, who are especially sensitive to how they’re perceived by their peers.

“There’s a very heightened sense of ‘Everyone’s looking at me,’ ” says Marsh.

Everyone was looking at Ahmed Wednesday, but most were looking to provide support and solidarity.

The hashtag #IStandWithAhmed was trending on Twitter all day on Wednesday. Ahmed himself opened his own Twitter account Wednesday morning (handle: @IStandWithAhmed) and had more than 37,000 followers by Wednesday afternoon. The account’s profile picture is the now-iconic photo of Ahmed in handcuffs and his NASA T-shirt. The north Texas chapter for the Council on American-Islamic Relations has said it’s investigating Ahmed’s arrest.

In the hours since he set the account up, Ahmed has been invited to visit NASA, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (his “dream school”), and the White House – a personal invitation from President Obama.

Experts think the show of solidarity could help offset any potential stigma or shame Ahmed may feel as a result of his arrest – solidarity that other, lower-profile students in Ahmed’s position rarely receive.

Jason Nance, an associate professor of law at the University of Florida Levin College of Law, writes in an article soon to be published by the Arizona State Law Journal, that one “should not underestimate the negative effects of arresting a student, even when that arrest does not lead to conviction and incarceration.”

“If an arrested student is readmitted to school, that student often suffers from emotional trauma, stigma, and embarrassment and may be monitored more closely by [campus police officers], school officials, and teachers,” he writes.

One student in Chicago, Keshaundra Neal, described how after being arrested at 13 for walking past a fight, her teachers "treated me differently."

"They saw me as someone who got into fights and got arrested," she added.

Schools across the country are becoming increasingly reliant on law enforcement to discipline students, which critics of the practice say can lead to further disengagement from school and increased delinquency.

"What happened to this student happens all the time to students of color in schools," says Shaun Harper, executive director for the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania who recently published a report on 13 Southern states where black students are disproportionately suspended and expelled. "Most other students who are suspended, expelled, unfairly disciplined in schools – most of them go unknown and have no supporters and are made to feel like what they did is wrong, even though what they did may not have been wrong."

"This case is very rare," he adds. "This student is getting the support he deserves."