Arkansas lethal injection case highlights larger issue of secrecy

An Arkansas county court judge will weigh in on a lawsuit by death row inmates against the state's secrecy of lethal injection, as pharmaceutical companies tighten the reins on distribution.

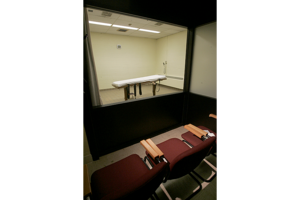

This November 2005 file photo shows the death chamber at the Southern Ohio Corrections Facility in Lucasville, Ohio. Ohio passed legislation earlier this year offering anonymity to pharmacies willing to manufacture drugs used in state executions.

Kiichiro Sato/AP/File

A judge in Arkansas on Wednesday heard arguments from the state to dismiss a lawsuit from death row inmates challenging the state’s secrecy law involving execution drugs.

An attorney for the inmates has argued that the secrecy law violates a settlement agreement from a previous lawsuit but the state argues that the law is constitutional. Pulaski County Circuit Court Judge Wendell Griffen said he will issue his ruling early next week, just one week before Arkansas’ first scheduled executions in almost a decade.

The drugs used in lethal injections have received heightened scrutiny in recent years as states have had a greater difficulty obtaining sufficient quantities of lethal injection drugs as pharmacies attempt to avoid the media spotlight.

As The Christian Science Monitor reported in March, two groups representing pharmacists, the American Pharmacists Association and the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists, recently advised their members to stop providing drugs used for legal injection.

“While neither policy is legally binding, experts suspect that the measures will dissuade specialty pharmacists, who recently became the only source for lethal injections in many states, from selling their products for use in executions,” the Monitor reported.

In response to decreasing availability, several states have tried to keep their lethal "cocktail" secret. Ohio passed legislation earlier this year offering anonymity to pharmacies willing to manufacture drugs used in state executions. The state of Virginia submitted an even more extensive bill, in an effort to keep all lethal injection information a secret, including the building where the executions take place.

But critics argue that such secrecy is unwarranted and unjust.

“Taxpayers who provide the funds that pay for the drugs used in lethal injections deserve to know when mishaps occur,” The Washington Post argued in an opinion piece in January. “The fact that such mishaps might arouse public disgust does not justify granting anonymity to drug companies that enter into government contracts.”

In 2014, the US Supreme Court refused to hear a case examining a death row inmate’s right to demand lethal injection disclosure prior to his execution.

Washington appellate lawyer Thomas Goldstein had urged the court to take up the case, as the Monitor reported at the time.

Because of the lack of judicial oversight, Goldstein argued that states are taking “calculated steps to shroud the circumstances of the lethal injection process in secrecy at the same time as drug shortages have led prison officials to experiment dangerously and irresponsibly with different pharmaceuticals.”

One of these dangerous experiments resulted in the botched execution of Oklahoma death row inmate Clayton Lockett last year. After receiving his lethal injection, Lockett struggled in pain for 43 minutes before dying.

The hindrance of pharmaceutical bad press is also evident in the Arkansas case. The Associated Press identified three pharmaceutical companies last month that likely made the state’s execution drugs, but all three companies objected to any relationship between their drugs and lethal injections.

This report contains material from the Associated Press.