California has the most gun-control laws in US. Do they work?

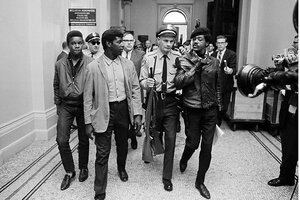

A California State Police officer escorts members of the Black Panther Party down the corridor of the Capitol in Sacramento, California, May 2, 1967. The armed Panther said they were protesting a bill before the Legislature restricting the carrying of arms in public.

AP/FIle

Pasadena, Calif.; and Cincinnati

California is by far the most regulated state in America when it comes to restricting the sale, use, and ownership of guns. Gun-control advocates call it the national leader, the “tip of the spear” setting the tone for other states, as Christian Heyne, vice president of policy at Brady, a gun-control advocacy group, puts it.

The Golden State also has had a series of high-profile public mass shootings in recent years – in San Bernardino, Thousand Oaks, and this week, San Jose. On May 26, a gunman opened fire on his co-workers at the rail yard facility of the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, killing nine people, then taking his own life.

Below, the Monitor looks at how California came to play this vanguard role, and the effectiveness of its approach.

Why We Wrote This

Under Ronald Reagan, California became the birthplace of the modern gun-control movement, and now has more than 100 laws. But how effective are they – and can they stop mass shootings like in San Jose?

How did California become the king of gun regulation?

On May 2, 1967, protesting members of the Black Panther Party marched into the Capitol in Sacramento carrying loaded handguns, shotguns, and rifles. Not long after, Republican Gov. Ronald Reagan signed into law a ban on openly carrying loaded firearms in cities and towns.

Since that time, though, it’s liberals who have been pushing for more regulations, though not always successfully. In 1982, California voters soundly defeated a ballot proposition to restrict handgun ownership. A strong 63% opposed the measure. But fast-forward and it’s the exact opposite. In 2016, that same percentage of voters backed a ballot initiative that banned high-capacity magazines and put new restrictions on ammunition sales.

The gunman in San Jose had semiautomatic handguns with magazines that were banned under a 2016 law. That law is currently awaiting an appeals court decision.

“Support for gun control has increased as support for the GOP has plunged,” says John Pitney, a professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California. In an email, he writes that the state turned blue in the 1990s, when Latinos pushed back against anti-immigration efforts, and the economy shifted from GOP-leaning defense workers to Democratic-leaning tech workers. Today, registered Republicans account for less than 25% of the electorate.

How effective are California’s gun-control measures?

As of 2020, California had more gun laws – 107 – on the books than any other state, according to research from the State Firearm Laws Database. And while those laws haven’t made California the state with the least amount of firearm deaths, it does put it around the bottom quintile, says Dr. Eric Fleegler, a pediatric emergency physician at Boston Children’s Hospital who researches gun violence and regulations.

Crucial, Dr. Fleegler says, are California’s laws on universal background checks – a solution to “a huge loophole in the federal background check” – as well as laws on gun storage, laws relating to gun ownership for people with a history of domestic violence, and people with restraining orders. These measures are intended to help with all types of gun violence – from suicides to accidents – not just murders and mass shootings.

“They really cover a broad gambit,” Dr. Fleegler says. But, he adds, where there are guns, there will always be gun deaths, intentionally or otherwise. “While legislation on the one hand can certainly lead to some reductions in the number of guns owned at the state level, they don’t actually prohibit the purchase of guns,” he says. “[Regulations] do a more thoughtful approach to who has them, how do you store them, if someone has domestic violence as part of their history, remove them from actually owning them.”

Mass shootings have an element of surprise or randomness that can make prevention difficult, even with other gun-control measures in place. “Those [shootings] are extremely distinct” from other forms of gun violence, Dr. Fleegler says. So-called red-flag laws, which allow for the confiscation of guns from those who are deemed a risk to themselves or others, can be a good step, he says. But “it’s one thing to pass legislation, it’s a whole other thing to enforce legislation,” he adds – as was highlighted when those laws didn’t prevent a recent shooting in Indianapolis.

What happened in 2020?

Gun sales in California – and the nation – surged last year, spurred by racial and political unrest, economic insecurity, and the uncertainty of the pandemic. According to state data released in March in a court case, about 1.17 million new guns were registered in the state in 2020 – the most since 2016. The buying spree continued into the first part of 2021.

In 2020, there were just two public mass shootings in which four or more people died – down from 10 in 2019, the worst year on record, according to experts on mass shootings. That’s due in part to pandemic lockdowns. However, overall shootings increased – with more than 600 incidents where four or more people were shot, up from 417 in 2019. And violence generally increased by 20% or more in many large and small cities, California’s included, writes Dr. Garen Wintemute, a professor of emergency medicine and violence prevention at the University of California, Davis. Through mid-2020, the size of the increase in violence was proportional to the size of the increase in gun sales, he writes in an email.

“There was ... social disruption on many fronts, on a scale we’ve not seen in many years. We are just beginning to experience the effects of those interacting changes,” he explains. “We are likely to have a rough summer.”

Has California’s approach caught on elsewhere?

When it comes to red-flag laws, “it was California that really created the model we see today,” where both police and family members can initiate the process, says Mr. Heyne at Brady. Indiana and Connecticut were the first states to have such laws. But following California’s passage, 16 states and the District of Columbia passed laws similar to the Golden State’s – including five with Republican governors.

California is also home to the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center, the first state-funded center for such research. It’s part of a holistic approach to gun violence “that is something that we have seen other states also pick up,” Mr. Heyne says. But after the San Jose shooting, “we still have a lot of work to do.”

Part of that work, advocates like Mr. Heyne believe, will have to come from Congress. California isn’t an island, he notes, and guns can flow across its borders. But the state has leaders at the federal level who’ve long championed gun control.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein was the architect of the 10-year federal assault weapons ban passed in 1994, and has pushed for its reinstatement. Her home state bans assault weapons. Other California Democrats, such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris, have also pushed for gun-control measures, though few reforms have passed at the federal level in recent decades.

Nationally, “we do very little to screen individuals or to separate [from firearms] individuals that we know are at risk of dangerous behavior,” Mr. Heyne says. “If we want to really address gun violence in all of its forms, we need a comprehensive approach that is tactical, that is surgical, that is very specific to addressing the types of gun violence that exist in America, because it’s not a monolith. All of these different forms of gun violence require different solutions.”