Auditors say billions likely wasted in Iraq work

After years of following the paper trail of $51 billion provided to rebuild a broken Iraq, the U.S. government can say with certainty that too much was wasted. But it can't say how much.

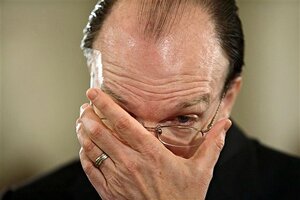

In this 2009 photo Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction Stuart Bowen testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington before the Wartime Contracting Commission.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

WASHINGTON

After years of following the paper trail of $51 billion in U.S. taxpayer dollars provided to rebuild a broken Iraq, the U.S. government can say with certainty that too much was wasted. But it can't say how much.

In what it called its final audit report, the Office of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction Funds on Friday spelled out a range of accounting weaknesses that put "billions of American taxpayer dollars at risk of waste and misappropriation" in the largest reconstruction project of its kind in U.S. history.

"The precise amount lost to fraud and waste can never be known," the report said.

The auditors found huge problems accounting for the huge sums, but one small example of failure stood out: A contractor got away with charging $80 for a pipe fitting that its competitor was selling for $1.41. Why? The company's billing documents were reviewed sloppily by U.S. contracting officers or were not reviewed at all.

With dry understatement, the inspector general said that while he couldn't pinpoint the amount wasted, it "could be substantial."

Asked why the exact amount squandered can never be determined, the inspector general's office referred The Associated Press to a report it did in February 2009 titled "Hard Lessons," in which it said the auditors — much like the reconstruction managers themselves — faced personnel shortages and other hazards.

"Given the vicissitudes of the reconstruction effort — which was dogged from the start by persistent violence, shifting goals, constantly changing contracting practices and undermined by a lack of unity of effort — a complete accounting of all reconstruction expenditures is impossible to achieve," the report concluded.

In that same report, the inspector general, Stuart Bowen, recalled what then-Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld asked when they met shortly after Bowen started in January 2004: "Why did you take this job? It's an impossible task."

By law, Bowen's office reports to both the secretary of defense and the secretary of state. It goes out of business in 2013.

Bowen's office has spent more than $200 million tracking the reconstruction funds, and in addition to producing numerous reports, his office has investigated criminal fraud that has resulted in 87 indictments, 71 convictions and $176 million in fines and other penalties. These include civilians and military members accused of kickbacks, bribery, bid-rigging, fraud, embezzlement and outright theft of government property and funds.

Much, however, apparently got overlooked. Example: A $35 million Pentagon project was started in December 2006 to establish the Baghdad airport as an international economic gateway, and the inspector general found that by the end of 2010 about half the money was "at risk of being wasted" unless someone else completed the work.

Of the $51 billion that Congress approved for Iraq reconstruction, about $20 billion was for rebuilding Iraqi security forces and about $20 billion was for rebuilding the country's basic infrastructure. The programs were run mainly by the Defense Department, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

A key weakness found by Bowen's inspectors was inadequate reviewing of contractors' invoices.

In some cases invoices were checked months after they had been paid because there were too few government contracting officers. Bowen found a case in which the State Department had only one contracting officer in Iraq to validate more than $2.5 billion in spending on a DynCorp contract for Iraqi police training.

"As a result, invoices were not properly reviewed, and the $2.5 billion in U.S. funds were vulnerable to fraud and waste," the report said. "We found this lack of control to be especially disturbing since earlier reviews of the DynCorp contract had found similar weaknesses."

In that case, the State Department eventually reconciled all of the old invoices and as of July 2009 had recovered more than $60 million.

The report touched on a problem that cropped up in virtually every major aspect of the U.S. war effort in Iraq, namely, the consequences of fighting an insurgency that proved more resilient than the Pentagon had foreseen. That not only made reconstruction more difficult, dangerous and costly, but also left the U.S. military unprepared for the grind of multiple troop deployments, the tactics of an adaptable insurgency and the complexity of battlefield wounds. It also left the U.S. government short of the expertise it needed to monitor contractors.

Although the audit was labeled as final, a spokesman for Bowen's office, Christopher M. Griffith, said several more will be done to provide additional details on what the U.S. got for its reconstruction dollars and what was wasted.