U.S. troops buy own gear for safety, style in battle

Since 9/11, the market for tactical war gear has grown to $150 million annually.

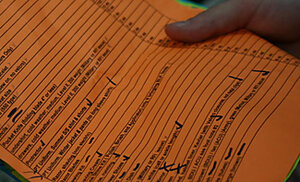

Packing list: Officers are given a list of items the need to buy before they deploy.

Patrik Jonsson

FORT BENNING, Ga.

Commando Military Supply on Victory Drive here is about as different from a musty Army surplus store as you can imagine.

More REI than M.A.S.H., Commando is regularly jam-packed with deploying grunts and sergeants, poking around for custom gear including $200 flashlights, $150 Oakley protective sunglasses, $180 Thinsulate boots, and $20 thermal socks.

"When you're comfortable and you know where all your gear is, it makes you a better fighter," says Lt. Tucker Knie, an Army Ranger perusing custom ammo pouches and techno-fiber socks. "You don't want to be rummaging around in your pocket during a firefight."

The traditional Army credo is that it's guts that win the glory – not fancy long-johns or Oakley sunglasses. But that old-school thinking is wicking away like perspiration through Gore-Tex as US soldiers today go beyond military-issue battle dress uniforms in favor of top-of-the-line gear to help them get home in one piece – and look sharp, too.

One reason, critics say, is that military procurement, especially of life-saving equipment, is still too slow. Quietly, however, the Pentagon – with the Army leading the charge – has begun bypassing rigid procurement rules, loosening uniformity requirements, and even spearheading technical innovations in gear, ranging from flame-retardant shirts to low-infrared signature zippers.

"The idea now is, 'If it helps Joe do the mission, let him have it – as long as it's not hot pink,' " says Army veteran Logan Coffey, founder of Tactical Tailor, a custom-maker of packs and pouches in Lakewood, Wash. "It's a giant change" in the military mind-set, he says in a phone interview.

Since 9/11, the market for tactical war gear has expanded from nearly nonexistent to nearly $150 million in sales each year, which includes sales directly to soldiers as well as to the Pentagon, according to industry sources.

CIA operatives, domestic SWAT teams, and Border Patrol agents are also rounding out their gear at bazaars like Commando.

To some critics, the sight of soldiers buying their own battle gear symbolizes a divide between frontline grunts and rear echelon procurement officers who may never have seen battle. Rep. Gene Taylor (D) of Mississippi told the House Armed Services Committee last week that supplies such as body armor and uparmored Humvees "[have] taken entirely too long" to get to frontline troops.

In some cases, charity groups have stepped in to help. Operation Helmet, founded by Bob Meaders of Montgomery, Texas, shipped special helmet liners to soldiers to replace what many soldiers said were poorly designed helmet pads issued by the Army and the Marines. Just as Operation Helmet thought its work was done late last year, more requests came in from troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"The Army is planning a $20 billion future combat system, and they can't provide boots that don't wear out," says Roger Charles, editor of DefenseWatch, an investigative website that advocates on behalf of frontline soldiers. "There's no priority for taking care of relatively mundane items where most people would think, 'Gosh, that's so simple. Why don't they have the best boots, the best uniforms, the best helmets, and the best flak jackets?' "

But through new and rejuvenated efforts like Program Executive Office (PEO) Soldier, the Soldier Battle Lab here at Fort Benning, and Soldier Systems Center in Natick, Mass., the Army has quickened the supply chain, sometimes against daunting odds, experts say.

For example, PEO Soldier's Rapid Fielding Initiative recently turned around an order for special mountain boots for units in Afghanistan in a month's time. "The Army has never been able to field such updated equipment so quickly before," says Lt. Col. John Lemondes, head of Clothing and Individual Equipment at Fort Belvoir, Va. "We really are moving at the speed of lighting with respect to equipping the war effort."

And at Ft. Lewis, Wash., one unit commander is putting an array of new protective glasses to the test this month. The unit will use discretionary funds to buy the glasses the soldiers prefer.

Moreover, the Army and Air Force Exchange Service reports that sales of tactical gear to units have climbed from $60 million in 2005 to $90 million in 2007. At the same time, there's evidence that soldiers are spending less of their own money on gear: One study found that two years ago, marines were spending $400 of their own money on extra gear; last year, they spent an average of only $100.

"The military is now doing a pretty good job of outfitting the war fighters with what they need, and a lot of it comes from effort and real caring," says Drumm McNaughton, a Navy veteran and management consultant who has written about the struggles of military procurement.

Because little enhancements can make a big difference, soldiers often choose to pick up their own "dirty packs" to augment the issued gear, especially as many feel flush from combat bonuses.

"What's 100 bucks for a flashlight if it's going to work during an attack, and help you fend off a knife fight?" says a Commando clerk, who didn't want to be named because he wasn't authorized to speak by the store manager.

But many soldiers don't blame the Army. One lieutenant shopping at Commando says standard issue gear is usually good enough. His one complaint: the clunky Army cap, which has a thick bill that can't be formed baseball-style. "They need to change it," he says. "It makes you look like a dork."

Even in life and death situations, fashion means something on the battlefield, soldiers say. "The Army does issue everyone glasses, but the young soldier wants to look cool, fashionable. He wants to look sexy," says Mr. Coffey.

The sales growth in custom tactical gear is partly made possible by manufacturing advances that allow companies to make profit on small batch orders. But for war fighters, a perk to the hard slog is being allowed to put their own spin on the Army look.

"One of the basic tensions is that in the Army there's pressure for a strong collective identity ... to develop this feeling of belongingness and camaraderie," says Frederic Brunel, a marketing professor at Boston University. "At the same time, there is a basic human need to pull away from that ... [to] retain some sense of self-identity that is separate from the group identity."