It took decades: Now there’s a photo for each name on Vietnam wall

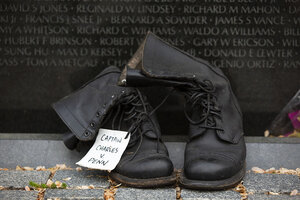

Capt. Charles Varence Penn's boots were placed in front of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial by a visitor, in Washington on April 28, 2021. Captain Penn, from Chicago, died in Vietnam on Nov. 29, 1969. Wall of Faces online pairs at least one photo with each of the 58,000-plus names inscribed on the memorial.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff/File

Volunteers have now tracked down at least one photo for every one of the more than 58,000 U.S. military service members who died in the Vietnam War – for an online Wall of Faces project that took more than two decades to complete.

The goal was to help a new generation of Americans grapple with sacrifice and inspire them to reflect, perhaps, on “why we have a wall” with names inscribed on it, say organizers from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), the nonprofit that spearheaded the digital project as well as the national monument on which all these names are engraved.

More than half of the visitors to the memorial in Washington, D.C., today weren’t alive when it was commissioned in 1982, they add.

Why We Wrote This

A volunteer labor of love has resulted in something remarkable: an online photo archive of every U.S. military service member killed in Vietnam, bringing their humanity home to current and future generations.

Over the years the picture-gathering process could be fraught: Relatives were sometimes reluctant to share photos of loved ones killed in battles picked by a government their survivors had come to distrust.

And stock photos taken straight out of, say, boot camp graduation can be surprisingly tough to come by. “The military doesn’t just sit there and funnel pictures to you,” says Herb Reckinger, a volunteer.

So tracking them down often involved investigative dedication, reaching out to local librarians, scouring yearbooks, and, at one point, combing through microfiche for a grainy image of a high schooler orphaned and homeless before he was drafted.

The project evolved into a quest, too, for photos that were actually good – meaning they showed a little personality, says Tim Tetz, director of outreach at VVMF.

Seeing young people in their prime, before they were soldiers, kicking back on a beach, cradling a newborn niece, or “sitting through that awkward school photo where their mom made them wear a funny sweater gets you to realize that they went through the same milestones and moments that each of us have gone through and really brings the sacrifice home,” he says. “You see the impact this war had on so many.”

Along the way, Mr. Tetz adds, the project “has provided some healing we didn’t envision when we started.”

One volunteer’s journey

When Mr. Reckinger, a retired oil refinery worker with a midwesterner’s disarming niceness, started volunteering for the Wall of Faces project, there were roughly 300 Minnesotans killed in the war without a picture on their VVMF profile.

He pasted a state map on cardboard and hung it on the wall with sticky notes marking their hometowns. Occasionally making “two or three trips for one guy,” since 2014 he’s dug through local historical society archives and teamed up with librarians to track down photos for 250 soldiers lost in the war.

Mr. Reckinger drew a “very low” draft lottery number for the Vietnam War, “but I joined the Navy Reserve for 5 or 6 years so as not to get drafted – I’m not extremely proud of it,” he says.

He’s one of a couple of dozen volunteers who spent several hours a day, and sometimes more, hunting for photos in Minnesota and, when that job was done, other states, joining a band ultimately totaling thousands of volunteers who helped in the collection effort.

Now that the project is complete, their job has evolved into finding more and better photographs for each of the names inscribed on the wall. “I always felt that the Vietnam soldiers deserved better,” Mr. Reckinger says. “I’m trying to see what a 70-year-old guy sitting in his basement can do.”

It turns out to be a fair amount. After the photos of one New York state soldier lost in Vietnam were destroyed in a 2009 fire at his mother’s home, Mr. Reckinger helped track down a relative and found an image.

Then there was David Kern, a Minnesotan who dropped out of 10th grade before school photo day. He’d left two foster homes and was sleeping in local sheds and cars.

He was taken in by a local family and “turned his life around” before he died in Vietnam. Mr. Reckinger, working with a local historian, was able to find a grainy photo from an obituary. “It’s one of the poorest-quality pictures you’ll ever see,” he says.

Still, Mr. Kern’s remembrance page on the wall – which gives biographical information and has room for viewers’ comments – has attracted dozens of notes of thanks from local students and fellow veterans. “You deserved to have a family,” one child wrote.

Surfacing deep feelings

Not all family members have been thrilled to be asked for photos of their loved ones. “Some would be very angry: ‘You can’t do this – we didn’t support the war,’” Mr. Tetz says. “It took us a long time to get them to work with us and understand we’re not the government and this is the purpose of what we want to do.”

That purpose is to memorialize, and also create community, he says. On one Wall of Faces remembrance page, a brother recalls ironing his shirt when Corporal Raymond Powell – who enlisted in the Marines at age 17 by taping sand-filled socks to his body to make minimum weight requirements – came home on leave. “I burned myself trying to look good for you,” Warfus Powell Jr. wrote in 2021.

A helicopter crew member posted a picture last year of the tiger that killed Corporal Gerald Olmsted – one of three casualties of war caused by big cats.

For Jacqueline Smith, who lost her big brother Richard Fina in 1968, the photos hammer home that these were “such young men,” she says.

In his last letter to his family, he signed off, “Don’t worry about me. I’m a devout coward.” He wasn’t – he was a medical corpsman killed by a sniper while providing aid to fellow servicemen who’d been shot.

His 51-person platoon had recently been whittled down to 13.

When Mr. Reckinger reached out to Ms. Smith for a photo of her brother, it wasn’t easy, she says. “I was 18 when he died, and you put it in a special place. It’s kind of hard to come back to that after you deal with it so many years ago.”

But Mr. Reckinger “did it in such a wonderful way,” she says. “I just keep thinking my mother would have been so tickled with the recognition.

“If it wasn’t for the picture, it would just be another name – you read about him and think, ‘Oh, that’s sad,’” she adds. “But you look at their young faces, and it just means so much.”