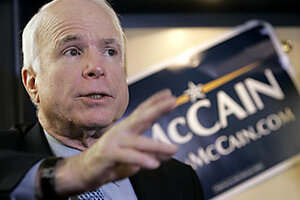

McCain fleshes out his economic plan

His challenge is to appeal both to the GOP's tax-cutting faithful and to independents and moderates.

Pushing his case: McCain proposes making Bush's tax cuts permanent. He would also eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax and double the personal exemption for dependents.

Mary Altaffer/AP

Washington

Presumptive GOP presidential nominee John McCain in recent weeks has put much time and effort into an attempt to bolster his credentials on a core issue of US politics: the domestic economy.

He's issued an economic plan more detailed than any he's talked about before. He's toured hardscrabble towns in an attempt to convey compassion for those worried about the future of their paychecks. He's used space provided him by the continuing Democratic slugfest to address an issue on which experts have long considered him to be weak.

It's a stab at political rebranding that may be long overdue, say some experts. But they add that it might be difficult for Senator McCain to craft an economic message that appeals both to the GOP's tax-cutting faithful and to the independents and moderates that the Arizona lawmaker needs to attract to win in November.

"McCain is trying to distance himself from Bush on the economy, but the eventual Democratic nominee will do everything they can to make him look like he's changed his first name to 'George,' " says Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

If "McCainomics" can be described in a sentence, it might be this: traditional GOP tax-cutting, with a dash of populism sprinkled on top.

To begin with, McCain would make President Bush's tax cuts permanent, rather than let them expire in coming years, as current law calls for. Critics say this is something of a switch for a lawmaker who opposed the tax cuts as too expensive when they were proposed.

He would eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax, which has eaten into the incomes of middle-class Americans. This move would cost $60 billion a year, according to campaign estimates.

McCain would double the personal exemption for dependents from $3,500 to $7,000, reduce the corporate tax rate from 35 to 25 percent, and establish a permanent new research-and-development tax credit. At the April 15 speech outlining his economic plan, he also called for the elimination of the federal gasoline tax this summer – a move that, strictly speaking, the next president would have to go back in time to accomplish.

McCain's tax cuts (excluding the gas tax holiday) would cost some $200 billion a year, according to his campaign. They would be offset by eliminating pork-barrel projects from the federal budget, freezing nondefense discretionary spending for at least one year, and reducing the growth of Medicare spending, among other moves.

As for the populist part, McCain railed against the extravagant salaries and severance deals of CEOs in his April 15 speech. Since then, he's toured small towns hard hit by the economic downturn and praised their work effort and role in the US economy. At the same time, he said increased government spending is not the answer to their woes.

Government "can't do your work for you," McCain said on April 23 in Inez, Ky. "And you've never asked it to."

Nationally, McCain is known for his security credentials, not his economic ones, note political analysts. McCain famously once said that he did not know much about the economy, notes Cal Jillson, a professor of political science at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

"He and his people decided they needed to address that [misstep]," Professor Jillson says.

In the Senate, McCain has been known for his opposition to what he sees as wasteful government spending and a traditional green-eyeshade approach to balancing the federal budget. At the start of the campaign, he indicated he'd balance Uncle Sam's books by the end of his term in office. Now, with his tax-cutting agenda fully outlined, he appears to have pushed back the potential date for black ink to the end of a possible second term.

Campaign officials say that McCain's tax proposals are offset by his budget initiatives. Budget hawks differ, saying that the savings from eliminating earmarks is exaggerated, among other things.

"The numbers don't come close to adding up," says Robert Bixby, head of the Concord Coalition, a budget watchdog group in Arlington, Va.

Not that the Democratic candidates have been any more rigorous in pursuit of fiscal prudence, according to Mr. Bixby. He says both Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama have proposed extensive, and expensive, healthcare plans, without fully preparing the public for their budget impact. "All the candidates have the same basic problem: They give specific policies that they will do, while providing only vague promises about how they will pay for them," Bixby says.

But it is the Republicans who currently control the White House – and that is a problem for McCain, in terms of economic policy. Voters tend to hold an incumbent party responsible for sour economic times during an election year.

McCain's task is to propose economic policies that appeal to Republican voters, without appearing as simply Bush, Part 2.

"If the recession is not short and shallow, it will be extremely difficult for him to win," says Professor Sabato of the University of Virginia.