Will Obama's rift with the left matter?

The left is hopping mad, not just that Obama cut a tax-cut deal with Republicans, but that he didn't put up much of a fight. But the breach may help him woo back independent voters in time for the 2012 election.

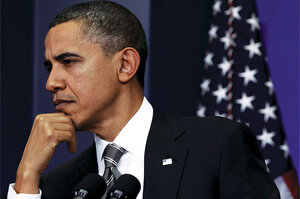

President Obama held a news conference at the White House Dec. 7 to discuss his deal on Bush tax cuts. Democrats and some Republicans were angry, but the tax-cut compromise could boost independent votes in the 2012 election.

Jim Young/Reuters

Washington

Phase 2 of the Obama presidency has started in earnest.

The new Republican-dominated Congress won’t be seated until January, but the reality of divided government has already hit home with President Obama’s liberal base. Gone are the days when Mr. Obama and congressional Democrats could pass big bills with nary a Republican vote. Enter Obama the compromiser, a prospect that fills liberal legislators and activists with frustration. On Thursday, the deal sparked a full-blown revolt by House Democrats.

To the progressive activists who worked hard for his election two years ago, Obama’s tax cut deal with Republicans came as a shock. Obama got two provisions he considered essential to the nation’s economic recovery: an extension of the Bush-era tax cuts for the middle class and a 13-month extension of jobless benefits for millions of unemployed people. But in exchange he gave in on extending the Bush tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, after pledging early and often during his campaign to end them. Democrats are also upset at the proposed new 35 percent estate tax, which would exempt inheritances of up to $5 million for individuals.

There’s no doubt the left is angry – not just that he cut this deal, but that he caved without much of a fight. But will this breach with his base mortally wound his reelection campaign, or will it actually help him win in 2012, by helping him woo back independent voters who abandoned the Democrats in the midterms?

The bottom line is the economy, says Democratic pollster Peter Hart. If this deal helps stimulate growth and bring down the jobless rate, that will please voters.

“Obama’s problem is not with the base, it’s with the center,” said Mr. Hart at a Dec. 8 Monitor breakfast with reporters. Speaking of the tax compromise, he added, “I’m sure he helped himself with independent voters at this stage of the game.”

In 2008, Obama campaigned on restoring bipartisanship to Washington, and after nearly two years in office, had little to show for it. Now he has no choice if he wants to get anything done, with Republicans soon to take over the House and gain seats in the Democratic-controlled Senate.

Still, it’s hard to listen to some voices on the left and not wonder if Obama is treading on thin ice.

“This fight over the Bush tax breaks for the rich may well be a tipping point in terms of how progressives feel,” says Justin Ruben, executive director of Moveon.org. “What people saw was just preemptive capitulation from the president on something he knew and we all knew was wrong.”

Mr. Ruben says it was Obama’s “moral vision” that inspired the grass roots to work for him and donate money two years ago. But going forward, “if you have no foot soldiers and no grass-roots donors, how are you going to win?” he says.

The left’s litany of complaints has only grown since candidate Obama faced the reality of governing. He gave up on including a “public option” – a publicly run health insurance plan – in his health-care reform. He has escalated the war in Afghanistan and failed to close the Guantánamo Bay detention camp. He has proposed a pay freeze for federal workers. He has concluded a South Korean free-trade accord that some Democrats say will cost Americans jobs. He set up a debt commission that proposed cuts in Social Security and Medicare.

“The big question for progressives is, where is he going to draw the line?” says Robert Borosage of the liberal Institute for America’s Future. “If he’s going to simply compromise, then first he’s going to get rolled, and he’ll get rolled worse and worse over time.”

Such talk seemed to infuriate the president at a Dec. 7 press conference, in which he called liberal complainers “sanctimonious,” with purist positions that would produce no victories for the American people. “Look, I’ve got a bunch of lines in the sand,” Obama said, starting with preventing tax cuts for top earners from becoming permanent, extending middle-class tax cuts, and prolonging unemployment benefits.

Growing GOP opposition to the tax-cut deal supports Obama’s contention that he wasn’t “rolled” by Republicans, and that they made concessions, too. Democrats in Congress are continuing to come out against the tax deal, saying they’re feeling railroaded into something on which they weren’t consulted. Vice President Joe Biden has made multiple trips to Capitol Hill to try to convince Democrats that Obama hasn’t betrayed them. In the end, even Democratic opponents of the proposal, such as Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts, predict it will pass.

For Obama, the ultimate hit from the left would be a serious primary challenge, which history shows is devastating to a president running for reelection. Just ask the last four one-term presidents, all of whom faced primary challenges that hurt them in the general election (or, in President Lyndon Johnson’s case, led him to drop out altogether).

Rabbi Michael Lerner, a liberal activist and magazine editor, has suggested that a primary challenger from the left would pressure Obama to adopt more progressive positions and thus rally his base.

But other left-wing activists don’t want to go so far on the “or else” aspect of their disaffection. Ruben of Moveon.org says liberals aren’t ready to abandon Obama by supporting a primary challenger, because there’s “too much at stake.” Instead, progressives want the “old Obama” back, says Ruben. “That means not giving up on him, but also not giving him a pass.”

Another factor that helps insulate Obama from a primary contest is his race. He has 90 percent support of the black community, which would rally to his defense in the face of a primary challenge.

The political landscape of 2012 will also become clearer once the Republicans have a nominee, and the choice becomes more concrete. A less-than-perfect Obama may look a lot better to progressives after they know the alternative. That’s probably what the White House is counting on. President Bill Clinton, after all, angered the left when he passed the North American Free Trade Agreement and welfare reform, and won reelection easily.

The difference between Mr. Clinton and Obama is expectations. Clinton campaigned as a centrist, while Obama campaigned as an agent of “hope and change,” a formulation that allowed a wide swath of the electorate to get behind him, including some Republicans and many independents. Elected with 53 percent of the vote, Obama took office with job approval ratings in the high 60s. Realistically, he had nowhere to go but down.

Among self-described Democrats, Obama still has 80 percent support. Still, he’s lost some who backed him enthusiastically two years ago. Michael Hare, a retiree from Rockville, Md., and a “lifelong Kennedy Democrat,” says he contributed thousands of dollars to Obama in 2008. Now, he would rather move to Canada than vote for Obama in 2012.

“After the euphoria wore off, nothing has gone to my satisfaction,” says Mr. Hare. “The bailout totally ignored the middle class.” On health-care reform, “we have industry writing policy,” he adds.

Among college students interviewed by the Monitor, Obama retains strong support, but they suggest he may have to work harder to replicate the enthusiasm among youths his campaign saw in 2008.

Kaley Hanenkrat, president of the College Democrats at Columbia University in New York, still counts herself as a supporter, though she calls the tax-cut compromise “really disappointing.” She is hoping for progress on other fronts, such as repeal of the Pentagon’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy that prevents gays from serving openly in the military.

Chloe Bordewich, copresident of the College Democrats at Princeton University in New Jersey, worked on behalf of the Obama campaign in 2008, and still supports him. But, she says, it’s “unbelievable the excitement and enthusiasm among students that he just let die away after his inauguration.”

Sara Johnson in Washington contributed to this report.