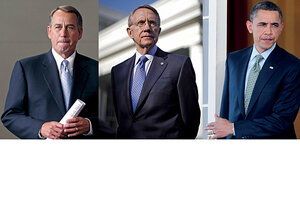

After budget battle Act 1, will Obama, Reid, Boehner have an Act 2?

Looming debt-ceiling talks may be a bigger hurdle for the three negotiators than the hard-fought deal on the 2011 budget. As for a deficit-cutting plan? Obama and Boehner are starting far apart.

Can House Speaker John Boehner, Senate majority leader Harry Reid, and President Obama (l. to r.) draw on lessons from bipartisan dealmaking on the budget?

From Left: AP, Reuters, AP

Washington

The face-to-face budget negotiations of three men – President Obama, Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio, and Senate majority leader Harry Reid (D) of Nevada – marked a rare plunge into bipartisan dealmaking in a Capitol addicted to partisan gridlock. Their engagement – and that of key aides, working nearly 24/7 – narrowly averted a government shutdown over the fiscal year 2011 budget.

The trillion-dollar question now is whether that hard labor has forged a working relationship that the three leaders can build on to tackle even bigger fiscal issues that lie ahead. Or not.

One hurdle may be that Democrats and Republicans emerge from Round 1 with different expectations for next steps. "There's nothing inevitable about this [first budget] deal," says Julian Zelizer, a congressional historian at Princeton University in New Jersey. "For Republicans, it's a precedent to cut more. For Mr. Obama, it's a precedent to think about something else besides spending cuts."

RELATED: Obama vs. Paul Ryan: Five ways their debt plans differ

Americans won't have to wait long to see if a spirit of dealmaking can persist. Already under way: jockeying over the 2012 budget. Up next: a politically perilous vote on the national debt ceiling, now at $14.25 trillion. (If Congress does not act to raise the debt limit, the US government would hit its ceiling on May 16 and – after using accounting measures to buy more time – default on its debt payments by early July, the US Treasury estimates.)

One takeaway from the three leaders' negotiation marathon: House Speaker Boehner, the lone Republican in the room, succeeded in using the threat of an angry, beyond-his-control, 87-strong GOP freshman class – pledged to roll back the size of government – to block "investments" in economic recovery and to leverage some spending cuts, though not as many as conservatives had wanted.

Now, with a Gallup poll showing that 6 in 10 Americans approve of the budget deal that slices $38 billion from spending for the next six months, the president has moved toward embracing the role of deficit slayer. When House Republicans rolled out their plan on April 6 to cut more spending into the future, Obama answered a week later by unveiling his own deficit-reduction proposal during a speech at George Washington University.

"Republicans have insisted on spending cuts and deficit reduction, rather than reviving the economy, and with this speech [Obama] shifted to their ground," says Mr. Zelizer. "This is a White House that feels that Republicans are powerful and have been successful in shifting the public to their issues."

In one respect, the fine art of dealmaking may make a comeback by virtue of divided government. When one party controls Congress and the White House, the template for moving major legislation is to jam it through. But with a new Republican majority controlling the House and the Senate still in Democratic hands, that approach won't work. The only option is to craft an agreement that can muster majorities in both the House and the Senate – and that requires patience, priority-setting, and an ability to mobilize outside groups to influence deliberations.

Obama, Boehner, and Reid now have one budget deal in their pockets, but its scope is modest compared with what comes next. On both the debt ceiling and the 2012 budget, which takes up the thorny issue of entitlement spending for Medicare and Medicaid, the two sides might as well be starting from different planets.

The debt ceiling

Obama wants a "clean bill" in which Congress simply votes to raise the limit.

Republicans want Congress to first put itself in a fiscal "straitjacket," such as statutory limits that trigger cuts when spending, the deficit, or debt exceeds a specified percentage of gross domestic product. If they don't get it, they say they'll allow the United States to default on its debt.

Default means the US could no longer sell securities to pay its bills, sending interest rates soaring and the stock market into free fall. "If you call into question the willingness of the government ... to meet its obligations, you will shake the basic foundations of the entire global financial system," Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner told a Senate panel on April 5.

The White House has laid down its marker. "We do not need to play chicken with our economy by linking the raising of the debt ceiling to anything," says press secretary Jay Carney.

Deficit-cutting and the 2012 budget

Republicans see the debt crisis as driven by government spending, period. Cut government and you create private-sector jobs, allow people to save for their future, and get the nation back on a sound fiscal path. Boosting taxes for top earners would burden small businesses and stifle job creation, they say. Without overhauling Medicare, Medicaid, and, eventually, Social Security, entitlement spending will drive the economy into a ditch.

The Republican vision is articulated in a 2012 budget plan crafted by House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, which the House approved on April 15, with nary a Democratic vote.

Democrats see the debt crisis as stemming from Bush-era tax policy that they say shields corporations and billionaires while demanding sacrifices from the poorest and most vulnerable. They call for a "balanced approach" to deficit reduction that includes overhauling the tax code to raise more tax revenue and robust oversight to protect consumers and the environment and to prevent Wall Street from engaging in practices such as those that triggered the Great Recession.

"The debate ahead of us is about more than spending levels; it is about the role of government itself," says Sen. Charles Schumer (D) of New York. "It will be one of the seminal debates in the first quarter of this new century, and it will determine what America is like."

How the public perceives the merits of each side is likely to influence what eventually emerges from Round 2. According to a Gallup snapshot at the onset, 61 percent of Americans say the government should make only minor changes in Medicare or not try to control costs, while 13 percent favor an overhaul. They are split on whether the FY 2012 budget should include major new cuts in domestic spending. On higher taxes for households with annual incomes of $250,000 or more, 59 percent say yea and 37 percent (including 60 percent of Republicans) say nay.

A bigger roster

Moving ahead, the players are likely to expand beyond Boehner, Obama, and Reid.

With the House budget plan for fiscal 2012 wrapped up, the Democratic-led Senate is scrambling to answer it. Reid is pushing the so-called Gang of Six to finish a bipartisan proposal that includes defense cuts and tax hikes. The six senators, mainly veterans of Obama's bipartisan deficit commission, have been meeting since December.

Obama has also asked congressional leaders to assemble a team of 16 for bipartisan, bicameral talks to devise a framework for "comprehensive deficit reduction" before July. That would require Reid to engage Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell, who largely stayed out of the FY 2011 budget talks, on the FY 2012 budget and the debt ceiling vote. Senator McConnell says Republicans will hold out for "something significant" on the national debt, before voting to raise the debt ceiling.

In the House, Boehner aims to keep pressing for spending cuts, entitlement reforms, and no new taxes. But he must also negotiate differences with his party's conservatives. Fifty-nine House Republicans didn't like the deal he reached with Obama and Reid on the 2011 budget and, on April 14, voted against it.

RELATED: Obama vs. Paul Ryan: Five ways their debt plans differ