Is the California economy finally turning a corner?

In California, the deficit for the current fiscal year is projected to be $1.9 billion, down from $25 billion in recent years. The unemployment rate and some home sales are also improving.

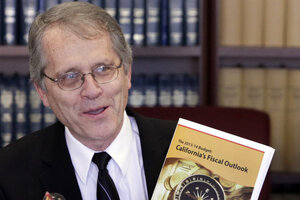

Legislative Analyst Mac Taylor displays a copy of his offices report on the state's fiscal outlook during a news conference in Sacramento, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 14, 2012. Taylor projected a much smaller deficit of $1.9 billion through the end of 20123 fiscal year in July 2013, as compared with the $15.7 billion deficit lawmakers faced earlier this year.

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

Los Angeles

There are several signs that California’s economic fortunes – after plummeting for half a decade – are on the rebound, buoyed by voter approval this month of tax-raising Proposition 30.

Here is the evidence:

• The independent California Legislative Analyst’s Office projects a relatively small $1.9 billion deficit for the current fiscal year – down from $25 billion in recent years. “There is a strong possibility of multibillion-dollar operating surpluses within a few years,” the Nov. 14 report concludes.

• The state’s unemployment rate has dropped 1.4 percentage points since October 2011 and is now at the lowest point since February 2009. The rate is still high, however: 10.1 percent.

• Home sales are increasing in some regions of the state, such as southern California, where they rose 25 percent in October compared with the previous year, according to the University of Southern California’s Lusk Center for Real Estate.

• A USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times poll from Nov. 18 indicates that the percentage of Californians who say the state is headed in the right direction has doubled since October 2011 – although the current figure is only 38 percent.

• New income is expected from the passage of not only Prop. 30, but also Prop. 39, which repealed an existing law that gave out-of-state businesses favorable tax treatment.

“The California economy and the state’s fiscal health is improving. For the first time in years, the budget situation is stable and thus state and local governments have more certainty about what to expect in the next year,” says Mark Baldassare, president of the Public Policy Institute of California, in an e-mail.

With California being the most populous state and having the world’s seventh-largest economy, the recent developments bode well nationally.

“California is the whale in the bathtub of the American economy. Signs of economic improvement in California have important positive national implications,” says Steven Schier, a political scientist at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn. “Given that the state's economy has been even more depressed than that of the nation as a whole, signs of a California rebound are quite positive for the country as a whole.”

Bond-rating firms have also weighed in, noting the $6 billion in additional annual revenues that are projected through 2016-17 because of Prop. 30. “California credit quality looks to improve with passage of Proposition 30,” says a Nov. 7 analysis by Standard & Poor’s.

All this said, several economists hasten to add that California’s improvement is only short term and that longer-term problems have not been addressed. They also note that the unemployment rate is still high.

“Short term, these are all good signs, but long term a lot still needs to be done,” says Kevin Klowden, managing economist and director of the California Center at the Milken Institute in Santa Monica, Calif.

About 80 percent of the revenue generated by Prop. 30, which was pushed by Gov. Jerry Brown (D), will come from higher taxes on high-income earners. But the revenue is temporary, lasting only five years, Mr. Klowden and others point out. And so the state’s income generation is not permanently changed.

“We are by no means out of the woods, but the ship is slowly turning and gathering momentum to positive growth,” says David McCuan, a professor of political science at Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, Calif.

He notes upticks in the high-tech sector and a record-breaking box office over Thanksgiving. “When you throw in the engine of Silicon Valley, the power of Hollywood, and an economic tailwind, the state will look a lot much closer to that thing called The American Dream and a lot less like Greece,” says Professor McCuan via e-mail.

Stumbling blocks ahead include pension reform, how cities handle bankruptcy threats, and how Washington deals with the “fiscal cliff.”

“Additional increases in taxes and regulations could slow business growth,” says Jack Pitney, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif. “We should not plan on the recovery being quick or even. Our state is unusually vulnerable to fluctuations in the stock market and the world economy.”

The current Legislature, he says, seems unlikely to handle public-sector pensions seriously. And other cities could go the way of San Bernardino, which declared bankruptcy in August, and Mammoth Lakes, which declared bankruptcy in June.

“There is a serious risk that more cities will go bankrupt, which would be very bad for the overall economic climate,” Professor Pitney says in an e-mail.

Still, California now has a nice window of time to deal with longer-term problems without the pressure of a crisis, some analysts say. Yet the outcome will depend on Governor Brown’s political ability.

“The proof of this rebound will depend on whether or not Jerry Brown can remain the prudent adult in the room and hold together the coalition that helped him win Prop. 30,” says Barbara O’Connor, director emeritus of the Institute for the Study of Politics and Media at California State University, Sacramento.