Does the US president need a dream team of historians?

Professors have proposed a team of historians who would advise the White House, a dual-purpose plan that would both inform policy-making and improve history education.

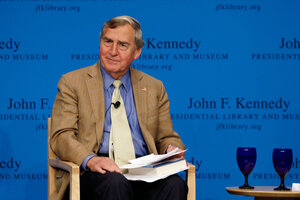

In this Feb. 5, 2013 photo, Graham Allison, Professor of Government at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School, listens during an event in Boston. He and a colleague have posited a team of historians who would advise the White House on historical precedents, a dual-purpose plan to both inform policy-making and improve history education in the United States.

Elise Amendola/AP/File

Among the ideas being floated during this year's presidential election is one from academia: creating a historian "dream team" to keep the president straight on dates and facts.

Two historians with Harvard University's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs have asked the winner of November's election to establish a Council of Historical Advisers at the White House.

"It isn't enough for a commander in chief to invite friendly academics to dinner," professors Graham Allison and Niall Ferguson wrote in The Atlantic. "The US could avoid future disaster if policy makers started looking more to the past."

The proposal creates an intriguing talking piece during a presidential campaign year, but it also highlights a deeper concern about Americans' historical knowledge that will resonate long after the November polls conclude.

Outright ignorance about key American historical events is a growing problem, surveys indicate. In 2010, the US Department of Education found just 12 percent of high school seniors achieved a "proficient" score on a nationally representative test, and only 22 percent could identify "China" as an ally of North Korea on a multiple-choice test.

A 2015 poll by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) found similar ignorance among even college graduates. Some 10 percent believed that TV personality "Judge Judy" was a member of the US Supreme Court, according to the poll, and only 20 percent knew that the Emancipation Proclamation halted slavery during the Civil War.

"When surveys repeatedly show that college graduates do not understand the fundamental processes of our government and the historical forces that shaped it, the problem is much greater than a simple lack of factual knowledge," the board wrote. "It is a dangerous sign of civic disempowerment."

Such misinformation has worked its way to the top, according to Dr. Allison and Dr. Ferguson, who argue that former presidents overlooked crucial history in making foreign policy missteps – not only regions' native history, but also the history of what US politicians have done there. The pair argue that former President George W. Bush, for example, failed to understand how conflicts between Sunni and Shiite Muslims would shape post-invasion Iraq; President Obama underestimated how Ukraine's warming relations with Western Europe would threaten centuries-old ties to Russia.

Neither the White House nor the current major political campaigns – Democratic or Republican – have issued any campaign promises in response to the historian council idea, the Associated Press reported. But demands to improve history education for American youth is beginning to grow among the public, says Glenn Ricketts, the public affairs officer at the National Association of Scholars, a New York-based network of professors.

He believes that American children fail to learn their history because teachers too seldom do the difficult work of teaching them how people in the past thought and felt about the problems they were trying to solve.

"I always like to tell my students, when they start griping, [about the self-taught schooling of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass] who had everything stacked against them, who worked so hard to read the very things that you’re so resistant to reading, and with remarkable results by all accounts," he says.

If nothing else, Dr. Ricketts tells The Christian Science Monitor by phone, increased attention to history at the highest levels of government might "trickle down" down to children's education and other key areas.

"Why stop at the president, let's go after the US Congress as well," he suggests. "Nothing wrong in making the same recommendations there."

He opposes the idea of long-term, institutionalized political appointees who might establish an "official history" but says historic advice for any sitting president could only help.

"It certainly would do no harm to have an eclectic group of historians give the president a reading list. I don't know what what he would do with it," Ricketts says. "If he's anything like most history students, he would probably find a way to get out of reading it."