‘People are just really unhappy’: Why Biden is so unpopular now

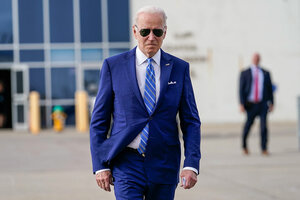

President Joe Biden walks across the tarmac to speak to the media before boarding Air Force One at Des Moines International Airport in Iowa, April 12, 2022. The president has been trying to emphasize his administration's accomplishments, such as the passage of the infrastructure bill.

Carolyn Kaster/AP

Washington

If there’s one thing political analysts agree on, across the spectrum, it’s this: President Joe Biden is in a slump. Left, right, and center; with young voters, Hispanics, and African Americans, the president’s job approval numbers are in the doldrums – and among key Democratic-leaning voter blocs, some polls show a marked decline.

The spike in gas prices and 40-year-high inflation are prime culprits. So, too, is the pandemic, grinding on into its third year. Russia’s brutal attack on Ukraine has not produced the kind of “rally around the flag” effect that American presidents often enjoy in the initial phases of an international crisis, despite early bipartisan praise for President Biden’s handling of the war.

Political polarization has hardened, analysts say, making it well-nigh impossible for any president to unify the country – a Biden campaign promise that has failed to materialize.

Why We Wrote This

Amid a slew of challenges at home and abroad, President Joe Biden’s job approval has tanked. Some factors may be beyond his control, but Democrats are hoping he can turn things around before the midterms.

“Mainly what we’re seeing is the strength of partisanship,” says Douglas Kriner, a professor of government at Cornell University.

All of the above bodes ill for Democrats’ prospects in the November midterm elections, which would be an uphill battle even in less challenging times. Since World War II, almost without exception, the president’s party has lost seats in the midterms – sometimes a lot.

Democrats, currently with narrow control of both houses of Congress, face the possibility of an energized Republican opposition holding power at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue come January and thwarting all but the most essential legislation.

That may explain the recent return of former President Barack Obama to the White House for the first time in five years. He was there to celebrate the 12th anniversary of the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare, the landmark legislation that added millions of Americans to health care rolls. An unspoken goal may have been to sprinkle stardust on his struggling former vice president. In fact, the visit by the gray-haired but still charismatic former president may have only served to emphasize their contrasting styles.

Still, Democratic strategists have far from given up on November.

Mr. Biden spent the “honeymoon phase” of his presidency with job approvals averaging just above 50%, a benchmark his predecessor, President Donald Trump, never reached. Now mired in the low 40s, there’s no reason Mr. Biden can’t do better going forward, Democrats say.

When asked by reporters about the November elections at the recent White House event, former President Obama suggested a way forward: “We’ve got a story to tell. Just gotta tell it.”

Matt Barreto, a Democratic pollster based in Los Angeles who does work for the Democratic National Committee, echoes that sentiment. “Democrats have to continue talking about what we have done, and reminding the American public that the Republicans don’t have a plan,” Mr. Barreto says.

He ticks off what he considers the biggest accomplishments of Mr. Biden’s first 15 months in office: the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, major infrastructure legislation, the rollout of a historic mass-vaccination program against COVID-19.

“Democrats are demoralized”

Celinda Lake, a Washington-based Democratic pollster who does survey research for Democratic Party committees, sees the president’s slump in the polls as a sign that “people are just really unhappy with life.”

“Of course they’re going to take it out on the president,” Ms. Lake says.

“The biggest concern I have is that the Republicans are supercharged, and the Democrats are demoralized,” she adds. “And we always have more trouble getting out our vote in off-year elections.”

She sees a forthcoming Supreme Court decision that may cut back on abortion rights, plus the House investigation into the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the Capitol, as potentially galvanizing for Democrats.

“Elections are a choice, not just an up-or-down referendum, and we need to start framing up the choice,” Ms. Lake says.

Perhaps most concerning for Democrats is Mr. Biden’s slumping approval among key demographics: young voters, Hispanics, and African Americans. The danger is that too many of these reliably Democratic voters will wind up staying home in November – not that they become Republicans.

Among younger voters, the decline in support for Mr. Biden has been especially marked. A Gallup Poll released last week showed that among Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2004), support for Mr. Biden has declined 21 percentage points since his first six months in office, from 60% to 39%. Among millennials (born between 1981 and 1996), the drop is 19 percentage points. Among Generation X (born between 1964 and 1980), it’s 15 points.

“Younger voters will need to feel real improvement in the economy” for them to be motivated to vote, writes Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson in an email. Many have been hit hard, for example, by a steep increase in rents.

“There are things that could change that in the short run and create a burst of attention and engagement – for instance, if a Supreme Court ruling makes an issue like abortion more salient,” she says. But “without addressing the underlying economic strain younger voters are facing,” she adds, “they may remain reluctant to turn out.”

Another X-factor in the midterms is whether “negative partisanship” – voting more in opposition to one party than in favor of the other – will play a big role. That could depend largely on how big a role former President Trump plays. In the 2020 election, he spurred high levels of voting not just among supporters, but also among opponents, who might otherwise have not been motivated to turn out for Mr. Biden.

The prospect of a comeback attempt by Mr. Trump in the 2024 presidential race looms large over the 2022 midterms.

“The question is how salient Trump or the threat of success by Trump-aligned candidates is for the average Democratic voter,” says John Sides, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University.

“Part of what the Democrats have to do is define the election in those terms,” he adds. “As always, it’s not just a referendum on Biden; it’s a choice between Biden and a Republican Party or Republican candidates that raise the risk of a return of Trump.”

Biden-Harris outreach

Mr. Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris have been traveling the country, highlighting infrastructure projects, and efforts to lower consumer costs and create jobs. Recently the administration has been reaching out to rural America, which has swung away from Democrats in recent years.

But looking overall at the decline in the president’s support, Mr. Sides isn’t sure how much Mr. Biden can do on his own to win it back.

“The culprit is, as always, things outside of Biden’s control much more than things under Biden’s control,” he says, pointing to the continuing pandemic, inflation, and fallout from the bungled U.S. pullout from Afghanistan last summer. Mr. Biden, he acknowledges, is responsible in part for inflation because of the American Rescue Plan’s size, and for what happened in Afghanistan.

On the other hand, Republican pollster Whit Ayres sees Mr. Biden’s challenges as mostly a self-inflicted wound. “He’s squandered the majority [support] he had a little over a year ago by the decisions he’s made and the way he has governed,” Mr. Ayres says.

He highlights what he sees as a premature declaration of victory over COVID-19, the initial dismissal of inflation as temporary, the messy withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the lengthy negotiating over the Build Back Better legislation, which has yet to produce results.

The foreign policy decisions made him look incompetent to the larger public, Mr. Ayres says, while the domestic policy negotiations harmed his standings among both liberal and moderate Democrats.

“It raised expectations of liberals before dashing them. So the left is demoralized,” he says. And “it made people who voted for him as a center-left moderate feel like they’d been sold a bill of goods – that he ran for president one way and governed another.”