Midterm matchup: When it comes to fundraising, so far Democrats lead

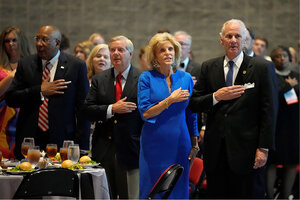

Republican National Committeeman Glenn McCall, U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham, first lady Peggy McMaster, and South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster stand during the Pledge of Allegiance during a South Carolina GOP fundraising dinner on July 29, 2022, in Columbia, South Carolina.

Meg Kinnard/AP

Democrats face many headwinds going into the midterms. But money may not be one of them.

Democratic candidates have raised substantial sums for their campaigns and are outpacing Republicans, particularly among small-dollar donors. In June, Democrats raised double the amount in small donations – $200 or less – than they raised in the same period for the 2018 midterms.

In key Senate matchups, Democrats are well ahead of their GOP rivals in fundraising. Take Ohio, where Sen. Rob Portman, a Republican, is retiring. Rep. Tim Ryan, a Democrat, raised $9.1 million in the second quarter. More than 97% of those contributions were $100 or less, according to his campaign. His overall take was four times that of his opponent, Republican J.D. Vance, though Mr. Vance has since had a cash infusion from a Senate political action committee.

Why We Wrote This

The president’s party often has a tough time in midterm elections, and Democrats face many challenges this fall. However, small-dollar donations, where they have outraised Republicans, offer a more nuanced picture.

A similar imbalance is evident in fundraising for Senate races in Georgia and New Hampshire. In Arizona, Republicans have now settled on a nominee, Blake Masters, which makes it easier to raise money to close the gap with incumbent Sen. Mark Kelly, a Democrat.

In general, Republicans are proving more effective in tapping large donors. National GOP committees are raising large sums for congressional and gubernatorial races. And while small donors have emerged as a powerful counterweight in campaign fundraising, big donors still matter in U.S. election spending. Super PACs, which can raise unlimited amounts for election-related speech, rely on wealthy individuals and corporations.

In the 2020 election cycle, candidates for Congress spent a record $3.68 billion running for office, according to Open Secrets, a watchdog group. An additional $5 billion was spent by party committees and outside groups. Many expect the 2022 midterms to cost even more.

In the past, Democrats led calls for greater limits on campaign finance, particularly after the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling in 2010 that loosened restrictions on spending by corporations and other entities. But those calls have since grown mute as the party has found ways to compete effectively with Republicans by courting wealthy donors as well as regular supporters, to the point where some GOP fundraisers complain of being outgunned.

“We get outraised on low dollar and on mega money,” says Dave Carney, a veteran Republican consultant in New Hampshire.

The Democratic advantage in small-dollar fundraising is partly explained by the strength of the party’s online platform, ActBlue, compared to the Republican equivalent, WinRed. Both platforms allow supporters to donate to almost any candidates or to national committees.

“Democrats have worked very hard to channel small-dollar donors toward candidates that need it,” says Robert Boatright, a political scientist at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who studies campaign finance.

Under President Donald Trump, Republicans closed the gap in online fundraising, as the former president built a formidable base of small-dollar donors. After his election defeat in 2020, Mr. Trump continued to rake in contributions and now controls a war chest of more than $120 million that many Republicans would like to see directed to midterm races. So far, Mr. Trump has spent little to support candidates he has endorsed, to the frustration of some GOP fundraisers.

Karl Rove, a veteran GOP strategist, has argued that such parsimony calls into doubt the effectiveness of Mr. Trump’s PACs. The former president’s fundraising pitches “have apparently produced a flood of contributions that donors think will help defeat Democrats. But it isn’t clear that much of Mr. Trump’s lucre is going to help in the midterms,” he wrote in a Wall Street Journal column.

Separately, some Republicans have complained that Google’s spam filter is biased against the party’s solicitations for online donations. Ronna McDaniel, who chairs the Republican National Committee, said Google had failed to explain why emails “sent to our most engaged, opt-in supporters” have been marked as spam. The company has pushed back on these claims. And analysts say a more likely explanation is that GOP donors are tuning out constant pleas for money, noting that Trump entities seem unaffected by the alleged bias.

Small donors are more representative of the voting public than large donors, says Laurent Bouton, an economics professor at Georgetown University and co-author of a study of millions of individual contributions between 2005 and 2020. Women and people of color were more likely to contribute small amounts to candidates, the study found.

Where small donors don’t differ from large donors is location: Most live in coastal states or large cities in the South and Midwest. But they’re more likely to support candidates from their party who live outside their district, which online platforms make it easy to do, says Professor Bouton.

“Small donors seem particularly attracted by races involving key figures of their party, or party nemeses, independently of where they are located,” he says via email.

Success in fundraising doesn’t always translate into electoral victory. Democrats outraised Republicans in several high-profile congressional races in 2020, only to see candidates fall well short. In North Carolina, for example, Democrats raised $182 million to challenge Sen. Thom Tillis, who defeated Cal Cunningham after revelations of infidelity clouded his campaign. Similarly, Sen. Susan Collins, a Republican, easily saw off a challenge from Democrat Sara Gideon after polls had showed a closer race. Ms. Gideon, the speaker of the state legislature, raised so much outside money that she ended with nearly $15 million unspent.

Well-funded Democrats also failed to unseat incumbent Republicans in Senate races in South Carolina, Texas, and Kentucky. This shows the limits of what money can buy for campaigns, says Mr. Carney, a political adviser to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott who will face Beto O’Rourke, a Democrat, in November’s election.

“All the [Democratic] money went to cause célèbres,” he says, noting that this strategy helps Republicans overall. “Every dollar that goes to a candidate that’s not in the hunt is wasted.”