Debt-ceiling deal holds hope of ending Beltway brinkmanship

House Republicans have used debt ceilings and 'fiscal cliffs' as political levers partly because Democrats in the Senate haven't passed a budget plan in three years. Now, that will change.

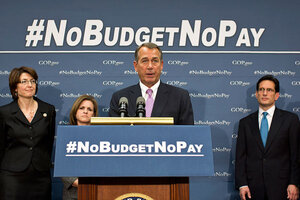

Speaker of the House John Boehner (R) speaks to reporters at the Capitol in Washington Tuesday. The House passed a bill Wednesday that would authorize withholding lawmakers' paychecks if their chamber fails to adopt a budget by April 15.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

Washington

The House of Representatives moved America away from another teeth-gritted trip to the edge of a financial abyss Wednesday by approving a measure that would put off a fight on the federal debt ceiling from mid-February to mid-May.

It is a bit more than the typical Washington kick-the-can-down-the-road move. In some ways, it could give Washington a road map to figuring out its fiscal situation with a little more regular order and a lot less brinkmanship.

That's because, simultaneously, Senate Democrats have agreed to pass a budget plan – something they hadn't done the previous three years. As a result, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle agree, much of the wrangling over America's fiscal future could be channeled away from manufactured debt-ceiling crises and "fiscal cliffs" and into an actual budget debate.

“If both chambers have a budget – a Democratic budget from the Senate, a Republican budget from the House – now you’ve got competing visions for how we address this problem” of debt and deficits, House Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio told reporters after the vote. “Out of those competing visions we’re going to find some common ground, I’m hopeful, that puts us on a path to balance the budget over the next 10 years.”

The final House vote was 285 to 144 in favor of the measure, with 86 Democrats (just under half the caucus) joining all but 33 Republicans. Some Republicans reversed their votes to oppose the bill after passage was assured.

Senate majority leader Harry Reid (D) of Nevada gave the bill his blessing, which suggests it should clear the Senate. On Tuesday, the White House said it would not stand in the bill’s way.

In addition to suspending the nation’s debt ceiling for three months, the measure also included a “no budget, no pay” provision that would put lawmakers' pay into escrow every day after April 15 that their respective chamber goes without passing a budget resolution. Lawmakers would receive their pay whenever they pass a budget or at the end of the congressional session in 2015, whichever comes first.

The bill’s passage allowed both sides to claim victory. Republicans hooted that they’d been able to push the Senate to commit to crafting a budget. Democrats said Republicans backtracked from their previous demand of tying debt-ceiling increases to dollar-for-dollar reductions in federal spending.

On Wednesday, Senate Democrats put their new willingness to craft a budget in a positive light. Senate Budget Committee chair Patty Murray (D) of Washington said the budget process could take some of the teeth out of two upcoming spending battles: the automatic spending cuts mandated by the "sequester" and the need to fund the federal government when a stopgap measure expires in March.

“The House Republicans can't have it both ways. If they want us – and we want to – to move a budget resolution through in regular process, then they can't have brinkmanship on every crisis that they manufacture for the next six months,” Senator Murray told reporters Wednesday. “So I hope that they stop doing this brinksmanship, bring our country back to a place where we can do the regular order as they have asked us to, move our budget resolutions through and find a resolution to reach a fair and balanced deal at the end of the day.”

Conservatives might not be ready to give up their perceived points of leverage yet.

“Under normal circumstances, this would not be a fight. You would just do a budget and be done with it. But we’re not under normal circumstances,” says Rep. Scott Garrett (R) of New Jersey, who wrote a 2012 federal budget proposal for the Republican Study Committee, Congress's most conservative caucus. On government funding and the sequester, he says, “we will have to let these things hit and deal with them one at a time.”

Then again, the budget is Congress's biggest fiscal lever. While House Republicans have passed a raft of conservative legislation, all of it has withered in the Senate. While budget resolutions are nonbinding – the money is actually authorized in a separate process – there's hope that doing the budget will be tantamount to a negotiation between the two parties over debt and government spending.

Rep. Rob Woodall (R) of Georgia, who mans the party’s right flank on fiscal issues, came away from a recent visit to Mr. Boehner's office impressed with the speaker's vision for the next round of budget fights.

“We have real opportunities in divided government, real opportunities, to come together to do the big things that matter,” Congressman Woodall said, quoting Boehner. "I take him at his word.”

Of course, there are stark differences between Republicans and Democrats about how to come together.

In 2012, House Republicans forwarded a plan that balanced the budget in 27 years. This year, House Republicans are vowing balance the budget within 10 years, meaning it will call for even deeper spending reductions than those decried by Democrats in 2012.

Senate Democrats not only will balk at the 10-year window, but they’ll also insist on tax revenues from ending tax expenditures and closing tax loopholes, a non-starter for the GOP.

But, at least for now, Congress has set up a process for reconciling these differences that isn’t the oft-repeated script of wedging budget debates into other issues because there was no Senate budget to debate.

“This is just the very start of Congress getting serious about budgeting,” said Rep. Jim Cooper (D) of Tennessee, the leading sponsor of “no budget, no pay” legislation in the House. “It’s just the start. We have a long way to go.”