Paul Ryan's tax numbers: Just 'magic asterisks'?

Paul Ryan's proposed budget envisions lower and simpler tax brackets even as it projects tax revenues as a higher percentage of GDP. Some suggest he'll need magic as well as math to get there.

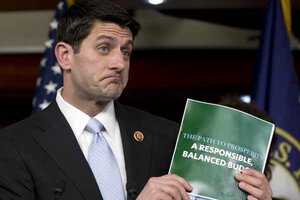

House Budget Committee Chairman Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., holds up a copy of the 2014 Budget Resolution as he speaks during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, March 12.

Carolyn Kaster/AP

Washington

Rep. Paul Ryan’s new budget doesn’t contain minute tax reform details. That’s not really his job – the Wisconsin Republican heads the House Budget Committee, after all. Taxes are the purview of House Ways and Means, whose chairman, Rep. Dave Camp (R) of Michigan, has vowed to produce a plan to remake the tax code at some point in the near future. Ryan’s waiting to follow Camp’s lead.

That said, the Ryan plan contains an interesting tax outline. Ryan’s laid out some revenue and reform goals that in some ways are more interesting than many of his spending top lines.

“The Ryan tax reform is totally fascinating this year!” said Ezra Klein of the Washington Post’s “Wonkblog” in a Tuesday video discussion of the plan.

First, there’s the revenue totals. Ryan’s fiscal year 2014 plan assumes collection of about $3.2 trillion more in taxes than did last year’s FY 2013 version. Partly that’s because the economy is getting better and producing more tax payments, per the Congressional Budget Office predictions that underlie Ryan’s work. But the Republican former vice presidential candidate also assumes that Uncle Sam will be corralling a bigger share of the US economy in coming years.

In 2023, when Ryan’s budget is supposed to reach balance, he has the US government getting taxes equal to about 19.1 percent of that year’s GDP. That’s higher than the equivalent number from last year’s Ryan effort, 18.7. Two years ago Ryan figured the government would be getting 18.1 percent of GDP in taxes 10 years out.

Republican orthodoxy is that taxes as a share of GDP should be going down, not up.

What’s happened here? Well, Ryan vowed that this time his budget would balance within a decade, and that’s a tough thing to accomplish. Look at it this way: his budget would repeal Obamacare, including its taxes on top earners meant to fund government health-care subsidies for those less well off. Ryan’s plan also would remake the income tax code so it only has two rates (more on this in a second). The top rate would be 25 percent as opposed to today’s 39.6 percent, which was just established in the fiscal cliff deal. Yet Ryan still counts the cash the Obamacare tax and 39.6 percent top rate would bring in.

“Thus this budget now accepts the extra revenues (though not the specific taxes) that Ryan and Hill Republicans so vehemently opposed just two months ago [in the fiscal cliff battle],” writes the Urban Institute’s Howard Gleckman in a Tax Policy Center analysis.

OK, now to the income tax. As we said he’d remake it into a two-tier system, scrapping today’s seven bracket rates. This is supposed to bring in the same amount of money as today’s system via reform that makes it “simpler and fairer,” in Ryan’s words. But he makes no mention of exactly what deductions and/or tax preferences would have to go to pay for the lower rates. He does not even explicitly commit to such broadening of the tax base.

Really this may be more aspiration than hard proposal. It’s cleverly done, too. Ryan’s budget does not explicitly say the top rate would be 25 percent. It says that’s the “goal,” leaving open wiggle room if it’s too hard to make the numbers add up.

And it would be hard to get them to add up.

“If you were going to get to a rate like this you would have to clean out almost everything in the tax code,” said “Wonkblog’s” Klein.

In that sense Ryan’s rate plan isn’t so much a plan as a manifesto, a statement of principles he’d like the nation to work towards.

It was another Midwestern GOP congressman of fiscal bent, Michigan’s David Stockman, who publicized the phrase “magic asterisk.” As Ronald Reagan’s first budget director, Stockman grew embarrassed about answering questions dealing with future deficits. He took care of them by inserting unspecified future budget reductions into the books – “magic asterisks.” (He credits Sen. Howard Baker (R) of Tennessee with actually inventing the term.)

Does it matter that some might judge Ryan’s tax calculations replete with magic asterisks? The Atlantic’s Matthew O’Brien thinks that it does.

“You’re not alone if you think magic is more fun than math. Paul Ryan certainly agrees,” O’Brien wrote Wednesday.

But not all pundits agree, even if they’re generally critical of Ryan and the House GOP.

“This is a budget, not a tax reform plan,” writes political scientist Jonathan Bernstein at “A plain blog about politics.” “As long as the tax cuts proposed in the budget are only intended – and will only be implemented – as part of revenue-neutral comprehensive tax reform, then who cares (from a budget point of view) whether it’s going to be possible to come up with enough offsets to make it work? If it doesn’t, then (presumably) tax policy just reverts to the status quo.”