Is long-term unemployment worse than it appears?

The Senate has voted to move forward with debate on renewing emergency benefits for those experiencing long-term unemployment. Some 1.3 million Americans saw such benefits expire on Dec. 28.

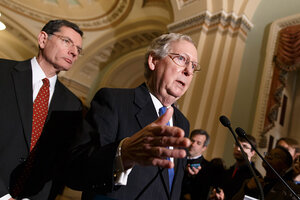

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., joined by Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., speaks to reporters following a procedural vote on legislation to renew jobless benefits for the long-term unemployed, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

Washington

A move to renew emergency benefits for the long-term unemployed passed a key procedural vote Tuesday, as 60 US senators voted to move forward with debate on the measure.

If the Senate approves the measure, it remains unclear whether the Republican-led House will follow suit.

The basic question at issue, economically, is whether the challenge of long-term unemployment is still big enough to warrant “emergency” response. That raises the question: Just how many would-be workers are unemployed for lengthy periods these days?

The answer is a lot, even using the Labor Department’s official tally of the unemployed. And the number goes higher, because not all the long-term jobless are included in that mainstream count.

Some 1.3 million Americans who have been out of work at least 26 weeks saw emergency benefits run dry on Dec. 28, when year-end budget talks left the program an unresolved issue and it expired. By some estimates, another 3.6 million people are likely to enter the ranks of the long-term unemployed (and to be eligible for the benefits if they reappear) at some point during 2014.

The total number of long-term unemployed goes beyond those eligible under an emergency benefits program, economists say. Consider that the program's 1.3 million beneficiaries, late in 2013, were just a fraction of the 4.1 million people whom the Labor Department counted as unemployed for more than 26 weeks. That larger group includes people who have already exhausted the extended benefits. Beyond the official long-term unemployed, more than 760,000 others are counted by the Labor Department as "discouraged," meaning they have stopped looking for work.

That’s the backdrop for the current situation, in which many labor-market experts on both the left and right are supporting the restoration of emergency benefits.

“Simply put ... it’s much harder for the long-term unemployed to find a job right now than it has been in the past when emergency federal benefits were allowed to expire,” writes Michael Strain of the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

The rationale behind unemployment insurance (UI) is to cushion workers and their families during the time it takes them to find a new job. In the current climate, another rationale for extending benefits is simply as an incentive for the jobless to not give up hope.

“It keeps them in the labor force looking for work,” says Chad Stone, chief economist at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington. People must keep up the job search to collect the support payments.

By contrast, dropping out of the job market tends to damage people’s earning prospects when they eventually try to jump back in, economists say. When that happens to a lot of Americans at once, it means lower productive potential for the whole economy.

“If we let emergency federal UI benefits expire, then the best guess based on the research is that more long-term unemployed workers will simply quit looking for a job and exit the labor force than will take a job they have been too choosy to take,” Mr. Strain wrote recently in the National Review.

Usually, the federal-state program called unemployment insurance provides income support for up to 26 weeks (half a year) after someone loses a job. The Labor Department considers anyone out of work longer than that, and actively on the job hunt, as among the “long-term unemployed.”

The Emergency Unemployment Compensation, or EUC, program, which was launched in 2008, makes jobless benefits run as long as 73 weeks per person in states with very high unemployment rates.

Some good news: America’s unemployment rate is now down to 7 percent of the workforce, as of November, well below its 10 percent recession-era peak.

But the progress still leaves long-term unemployment much higher than usual.

The long-term unemployed alone account for 2.6 percent of the US labor force. That’s down from a post-recession peak above 4 percent, but it’s still far higher than the number usually is even in the depths of a recession.

The benefits typically pay an amount equal to about half a worker’s prior salary.

Progress in the overall job market, meanwhile, can mean the emergency benefits for individual workers shrink. That’s because the law works on a formula where the duration of benefits hinges on a state’s unemployment rate.

In most states, unemployment has fallen enough that, if the emergency benefit is renewed, it will mean individuals have aid for 40 to 63 weeks, not the 73-week maximum.

Even before the EUC program expired in December, only 41 percent of unemployed workers were eligible for and receiving either state or federal jobless aid, down from 65 percent 2010, according to the National Employment Law Project, which is pushing for Congress to extend the benefits.

This shift is occurring even though it’s still taking people much longer than normal to find new jobs.

The average duration of unemployment was 37 weeks as of September 2013 – more than 20 weeks longer than pre-recession levels, and down by only 1.2 weeks since the end of 2012, the National Employment Law Project says.

All this helps explain why some Republicans joined Democrats in the Senate to move forward with debate on restoring EUC.

Many Republicans in Congress argue that extending the benefits again should be contingent on making sure the move doesn’t add to federal deficits – such as by finding new spending cuts to offset the cost.

One lingering question is how many long-jobless Americans have dropped out of the labor force. Although the Labor Department counted 762,000 of these “discouraged” workers in November, some economists point to declining participation in the labor force as a hint that the number may be higher.

If the participation rate matched pre-recession levels, some 5 million additional Americans would be in the labor force today. But it’s hard to know how much of this post-recession decline is due to the weak job market and how much is due to baby-boom demographics, as growing numbers of adults turn 65.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke told a gathering of economists in November that the Fed will be looking for clues on this point as it weighs whether the economy and job market are returning to health over the next couple of years.

What’s clear, though, is that the problem of long-term joblessness remains large.