'Kentucky kickback': an issue for Mitch McConnell or just friendly fire?

The deal ending the government shutdown included an obscure, one-line change to an unrelated law that increased authorization for spending on a massive water project in Kentucky, the home state of Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell.

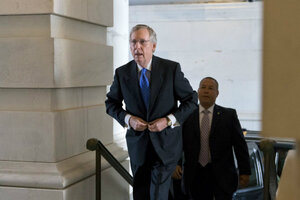

Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R) of Kentucky arrives at the Capitol on Oct. 16, just before striking a deal with majority leader Harry Reid (D) of Nevada to reopen the government. The deal also authorized $2.9 billion for a dam project in Kentucky that sparked controversy.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

WASHINGTON

Here’s what’s known about the so-called “Kentucky kickback,” a controversy that blew up just as Senate leaders were signing off on a deal to end a government shutdown and avert default on the national debt.

While the Senate had held out for a "clean" bill to fund government in its standoff with the House, the deal that Senate leaders took to the floor on Wednesday included an obscure, one-line change to an unrelated law that increased authorization for spending on a massive water project in Kentucky, the home state of Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell.

It didn't spend $3 billion, as critics quickly charged. It authorized a new cap of $2.9 billion for a project that had already spent well beyond the $775 million level authorized by law. (More on that later.) Nor was it, technically, a banned spending "earmark." But it smelled bad. Conservative critics, who viewed the Senate deal as a sellout and Senator McConnell as the traitor, dubbed it the "Kentucky kickback." [Editor's note: In the original version, the number in this paragraph was incorrect.]

Pork projects, or member earmarks on spending bills, were once common practice in Washington. After Republicans took back control of the House in 1995, pork projects soared – peaking at $29 billion in 2006, the year the GOP lost control of the House after scandals involving bribes for earmarks. In 2010, a new GOP majority banned the practice, and the Senate followed suit.

What makes earmarks toxic is the appearance of special favors for the powerful, drawn up in secret, and not vetted by any government agency or subject to competition from other projects.

But the Olmsted Locks and Dam project, spanning the Ohio River between Olmsted, Ill., and Paducah, Ky., is no "bridge to nowhere," the notorious Alaska earmark that launched the drive in 2005 to end earmarks. The dam replacement project aims to ease a bottleneck for barges about 17 miles upstream of the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The Army Corps of Engineers calls the site "the busiest stretch of river in America's inland waterways."

When Congress first authorized the project in 1988, the estimate for completion was $775 million. By FY 2011, costs had soared to more than $1.4 billion, and the Army Corps says it will need authorization to spend up to $2.9 billion to finish the work. Despite delays and cost overruns, the project retained bipartisan support. The proposed increase was included in President Obama’s FY 2014 budget and authorized by both Senate and House committees.

It's not clear whether Senate leaders expected the blowback they're getting on this project. Accounts from aides, who will not be quoted publicly, differ on this point. What is clear is that Senate leaders, on both sides of the aisle, quickly rallied to its defense.

Both McConnell and Senate majority leader Harry Reid denied that the project was an earmark or that McConnell had requested it. Sen. Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee, the top Republican on the Senate Energy and Water Development subcommittee, said in a statement that he and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D) of California, who chairs the panel, had requested the project and that it would save taxpayer dollars.

“According to the Army Corps of Engineers, $160 million taxpayer dollars will be wasted because of canceled contracts if this language is not included,” Senator Alexander said, in a statement.

So, if it's not an earmark and McConnell hadn't requested it, what’s the problem?

One problem is that Senate leaders promised a “clean” bill but delivered a $2.9 billion add-on that benefited one of the principal negotiators of the deal, who is also up for reelection in 2014, as is Senator Alexander.

“It’s a big amount of money in a bill that was supposed to be clean, so everyone started screaming pork,” says Thomas Schatz, president of Citizens Against Government Waste (CAGW), a public interest group which tracks pork projects and government spending.

"There are other projects like this around the country where it could be more expensive to taxpayers to delay the funding or the project," he adds.

At a time when Congress’s approval rating is at near record lows, special treatment for powerful members is a red flag for critics and can be a big liability for individual lawmakers.

When news broke that Sen. Ben Nelson (D) of Nebraska, a critical swing vote for the president’s health-care reform in 2009, had also negotiated a special funding stream for Nebraskans in that bill, critics dubbed it the “Cornhusker kickback.” McConnell called it, “a smelly proposition.” Senator Nelson faced criticism about it right up until his decision to not seek reelection.

But in McConnell's case, the fire wasn't coming from across the aisle but from a civil war deep within GOP ranks. The Senate Conservatives Fund, known for funding primary campaigns against GOP incumbents not deemed conservative enough, broke news of the special provision soon and went on the attack.

“In exchange for funding Obamacare and raising the debt limit, Mitch McConnell has secured a $2 billion Kentucky kickback. This is an insult to all the Kentucky families who don’t want to pay for Obamacare and don’t want to shoulder any more debt,” said SCF Executive Director Matt Hoskins, in a statement on Wednesday.

On Friday, the SCF endorsed tea party candidate Matt Bevin against Senator McConnell in the 2014 Senate primary.

So far, the controversy has barely registered in the Kentucky Senate race. Neither Mr. Bevin, nor McConnell's likely Democratic opponent, Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes, have questioned funding for the dam, in a state where politicians often run on what they are able to send back home from Washington.

"There was no earmark," McConnell said in an interview with WVLK news radio in Lexington, Ky. on Friday. "Every single member of the Senate had a chance to review it and none asked for it to be taken out, and the committee points out that this authorization actually saved $160 million for taxpayers and it's pretty rare when you're able to save money in a spending bill."

Still, as McConnell said of the Cornhusker kickback, the special treatment for this project strikes many critics as "a smelly proposition."

"Congress's reputation has been adversely affected by the shutdown, and now by spending in this not-so-clean continuing resolution," says CAGW's Schatz. "They set themselves up for this criticism, whether it is warranted or not. It doesn't matter whether this particular project is an earmark, that's what everybody is calling it."