Pollsters blow it in British election. What lessons for the US?

When Conservatives won a clear majority in British elections this week, it stunned pollsters and pundits predicting a close race. Experts say the art and science of polling is changing, and this could impact next year’s US presidential race.

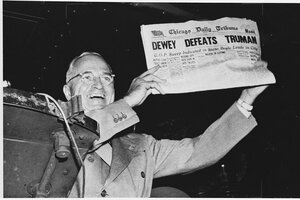

President Harry Truman, who won re-election in 1948, beating Republican Thomas Dewey, holds a copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune.

U.S. Information Agency

Britain had its “Dewey Defeats Truman” moment this week.

Tory leader and incumbent Prime Minister David Cameron defied pre-election polls – which had predicted a very close race and the likely need for a coalition government – winning an outright majority.

Pollsters and pundits were stunned.

"Election results raise serious issues for all pollsters. We will look at our methods and have urged the British Polling Council to set up a review," said Populus, one of the main polling firms, on Twitter.

“There are likely to be variety of reasons behind the difference in the polls and the final outcome,” Populus founder Andrew Cooper wrote. “Very late swing to the Conservatives, polling weightings, polling methodology and claimed propensity to vote will be just some of the factors that are likely to be discovered once an investigation is completed.”

"It's a very, very big miss and at this stage we just don't know why,” British political scientist Rob Ford told Reuters. “We're shocked.”

Prominent American political operatives were closely involved in the British election.

Obama campaign veteran David Axelrod advised big loser Ed Miliband and the Labor Party while another top Obama aide, Jim Messina, advised Prime Minister Cameron and the Conservatives. As the stunning results became clear, Messina tweeted: “Things US&UK have in common: completely broken public polling & re-electing their strong leaders.”

"In all my years as journalist & strategist, I've never seen as stark a failure of polling as in UK,” Axelrod groused on Twitter. “Huge project ahead to unravel that.”

For Messina, lessons learned from the polling debacle may be particularly relevant. He co-chairs Priorities USA Action, the outside group that’s raising money to support Hillary Rodham Clinton’s campaign.

There are major differences in the two countries’ election systems, of course. The campaign period in the UK is far, far shorter, and the kingdom has more political parties winning (or losing) seats under a parliamentary system.

But both political systems rely heavily on polls – conducted for news organizations and privately for candidates – and in the US, one of the most respected political statisticians got it glaringly wrong too.

Nate Silver, formerly of the New York Times and now writing his FiveThirtyEight blog as part of his gig with ESPN, was forecasting 272 seats for Conservatives and 271 for Labor – dead even. It takes 326 seats for a clear majority, and in the end Tories won big with 331 seats – 99 more than their main rival Labor.

How does Mr. Silver (who correctly predicted the outcome in the last three US presidential elections) explain this?

“Perhaps it’s just been a run of bad luck. But there are lots of reasons to worry about the state of the polling industry,” he writes. “Voters are becoming harder to contact, especially on landline telephones. Online polls have become commonplace, but some eschew probability sampling, historically the bedrock of polling methodology. And in the U.S., some pollsters have been caught withholding results when they differ from other surveys, ‘herding’ toward a false consensus about a race instead of behaving independently.”

It’s something Silver has worried about for some time.

For one thing, he wrote last August, “Response rates to political polls are dismal” – down to 10 percent from about 35 percent in the 1990s. Also, there are fewer top-quality polls (which are very expensive) as news organizations look for ways to trim budgets.

“Then there are the companies that have cheated in a much more explicit way: by fabricating data,” Silver wrote.

In his current analysis of the British election, Silver notes other recent elections where the polling was off:

• The final polls showed a close result in the Scottish independence referendum, with the “no” side projected to win by just 2 to 3 percentage points. In fact, “no” won by almost 11 percentage points.

• Although polls correctly implied that Republicans were favored to win the Senate in the 2014 U.S. midterms, they nevertheless significantly underestimated the GOP’s performance. Republicans’ margins over Democrats were about 4 points better than the polls in the average Senate race.

• Pre-election polls badly underestimated Likud’s performance in the Israeli legislative elections earlier this year, projecting the party to win about 22 seats in the Knesset when it won 30.

“In fact,” Silver writes, “it’s become harder to find an election in which the polls did all that well.”