What does the left want (besides Liz Warren for president)?

Some of the most visible progressives in the US think now is the time to pull policy in general, and the Democratic Party in particular, more toward their side of the political spectrum.

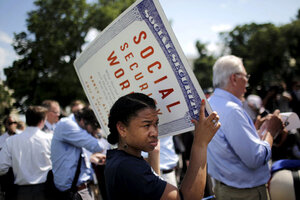

A woman holds a sign as she attends an event in support of New York Mayor Bill de Blasio's progressive agenda against income inequality outside the US Capitol in Washington May 12.

Carlos Barria/Reuters

Washington

What does the left want? Nothing less than a sweeping overhaul of the relationship between American political power and the American economy, that’s what.

Emboldened by the rise of inequality as an issue in the early stages of the White House 2016 campaign, some of the most visible progressives in the United States think now is the time to pull US policy in general, and the Democratic Party in particular, more toward their side of the political spectrum. And their agenda is an ambitious one, stretching well beyond the traditional liberal solutions of higher tax rates and expanded social benefits for the disadvantaged.

Inequality is largely a result of regulatory and legislative choices made by Washington since the 1980s, in the view of some prominent liberal economists, and thus it can only be remedied by a systemic fix. That might stretch from efforts to bolster wages and government support for families, to expanded Social Security, a revamp of taxes on business and the wealthy, and a tough new Wall Street regulatory regime.

“It would be easier, politically to push for one or two policies on which we have consensus, but that approach would be insufficient to match the severity of the problems posed by rising inequality ... We cannot alter the dynamics of our distorted economy without broad, bold, and comprehensive measures to put the United States back on track,” wrote economist Joseph Stiglitz in a lengthy report released last week by the liberal Roosevelt Institute.

Last week self-proclaimed progressives held a rally on Capitol Hill to push their point of view, with New York Mayor Bill de Blasio playing the role of ringmaster. Their list began with a $15 minimum wage, greater collective bargaining power for unions, and equal pay for women. It included federally-mandated paid family leave, plus universal, free pre-kindergarten programs, and government help with child care costs. As for banks, break ‘em up if they’re “too big to fail” and raise taxes on capital gains, dividends, and corporate income.

Liberals want expanded Social Security and a public option for Obamacare, as well. They compared their proposed policy agenda to the famous “Contract With America” laid out by the House Republican leadership during the 1994 congressional campaign.

“We knew it would take a bold set of solutions, that no half-measures would do,” said Mr. de Blasio.

The systemic approach, according to Mr. Stiglitz, is necessary because the years-long trend of increased inequality was not a natural development. He says it was a political choice. Reduced regulation of industry was the beginning, in his view, followed by lower marginal tax rates, then cuts in spending on social welfare.

“Our institutionalist approach is based on two simple economic observations: rules matter and power matters,” Stiglitz writes.

Why push for this manifesto now? After all, Republicans are almost certain to control at least the House after the 2016 elections, if not the House and Senate – and maybe the White House, too. There’s almost no chance a holistic liberal approach will be enacted into law anytime soon.

Hillary Clinton, the odds-on choice for Democratic standard-bearer, has long been seen as a more centrist, even Wall Street friendly politician. That’s why liberals have long begged firebrand Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D) of Massachusetts to run.

But politics can be a long game, particularly when attempting to influence the nation’s basic ideology. And progressives think they can sway ex-Secretary of State Clinton, given that she appears to have moved to the left since her 2008 presidential run and has centered much of her initial campaign rhetoric about inequality and other issues progressives care about.

“Hillary Rodham Clinton is running as the most liberal Democratic presidential front-runner in decades, with positions on issues from gay marriage to immigration that would, in past elections, have put her at her party’s precarious left edge,” writes Washington Post political reporter Anne Gearan in an examination of the relationship between liberals and the party’s likely presidential nominee.

It’s important to remember that Clinton is still running for the Democratic nomination, though. Yes, she’s an overwhelming favorite, but she still needs to wrap it up and then establish solidarity in the party. It’s a time honored tactic for candidates to tilt left (or right) in the primaries and then run back towards the center in the general election.

In that context liberals may end up disappointed, even if Clinton wins. After all, presidents cannot just implement policy on their own. For important changes they must cajole Congress to pass bills – a daunting prospect, as President Obama knows. And the parties which presidents head aren’t themselves uniformly ideological. They’re coalitions of different factions which often disagree, as the GOP’s struggle to reconcile the tea party and establishment wings of the party shows.

It’s possible to move a party ideologically, according to Jonathan Ladd, an associate professor of political science at Georgetown University, but it’s a slow process that takes place over multiple presidential administrations.

“I think that Hillary [would] govern more liberally than Bill did on several issues but [would] still disappoint the most liberal members of the Democratic Party,” writes Ladd in an e-mail response to a reporter query.