GOP debate: Should US deal with dictators?

In Tuesday night's GOP presidential debate, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, and Rand Paul all said that overthrowing Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad would only benefit the Islamic State.

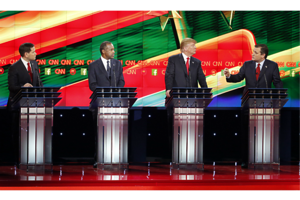

Ted Cruz, right, speaks during an exchange with Marco Rubio, left, as Ben Carson, second from left, and Donald Trump look on during the CNN Republican presidential debate, Tuesday, Dec. 15, 2015, in Las Vegas.

John Locher/AP

Tuesday night’s Republican debate had some head-scratching moments. Donald Trump appeared to not understand the phrase “nuclear triad,” which describes the bombers, subs, and missiles of the US strategic arsenal. Ted Cruz kept talking about carpet-bombing the Islamic State while limiting civilian casualties, which might be hard. Ben Carson said he was qualified to be commander in chief because he’d run a national scholarship program.

But the Las Vegas showdown also featured bursts of substance. At one point, it even touched on one of the most consequential and enduring questions of American foreign policy: Should the United States ally itself with dictators who support its interests?

At its heart, this is about whether realism should trump (sorry) idealism when presidents deal with the rest of the world.

The subject was the Syrian civil war. More specifically, it was about Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, and whether the US should continue to press for his ouster. It is Obama administration policy that Mr. Assad needs to leave his position as a precondition to any Syria settlement. US officials argue that he is a cruel dictator who has gassed his own civilians and destroyed much of his own country in an effort to cling to power.

A “surprising” number of the assembled Republican hopefuls said they opposed overthrowing Assad, notes the debate analysis of Foreign Policy. Mr. Trump, Senator Cruz, and Rand Paul all said that doing so would only benefit the Islamic State, which is one of the strongest fighting forces opposing Assad’s government.

“There are still people – the majority on the stage – they want to topple Assad,” said Senator Paul at one point. “And then there will be chaos, and I think ISIS will then be in charge of Syria.”

Cruz developed the idea further. He linked the idea of getting rid of Assad to being a “Woodrow Wilson democracy promoter” – in other words, an idealist who wants to promote (some would say impose) US values and modes of government on the rest of the world.

Take Libya, said the Texas senator. The Obama administration led NATO in toppling Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi in the name of democracy. Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, among other Republicans, supported this intervention at the time.

But chaos, not free government, was the result. Libya is now a war zone infested with terrorists, Cruz said.

The same thing happened in Egypt, according to Cruz, where the US helped push out longtime ally Hosni Mubarak, fueling the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood.

“We need to learn from history,” Cruz said. “These same leaders – Obama, Clinton, and far too many Republicans – want to topple Assad. Assad is a bad man. Qaddafi was a bad man. Mubarak had a terrible human rights record. But they were assisting us – at least Qaddafi and Mubarak – in fighting radical Islamic terrorists.”

Senator Rubio, perhaps the most hawkish of the Republican candidates, responded by saying that the revolt against Mr. Qaddafi was powered by the Libyan people, not the US government.

The US has to work with less-than-perfect allies around the world, Rubio said. But those do not have to include someone such as Assad, who has backed the Lebanese-based terror group Hezbollah and provided Iraqi insurgents with improvised explosive devices to use against US troops.

If Assad goes, “I will not shed a tear,” Rubio said.

The exchange symbolized the nature of the larger foreign policy debate within the GOP presidential race. Rubio is probably the closest of the candidates to being a George W. Bush-style interventionist. On the other pole is Paul, a libertarian-leaning candidate suspicious of US forays overseas.

The rest are in varying positions in the middle. Cruz is wagering that he can combine Paul’s opposition to expanded government surveillance with calls for an expanded bombing campaign against the Islamic State to present himself as a new kind of US realist.

Some critics complain this is a bit of a muddle. Cruz is portraying the Islamic State as one of the great challenges to the US of modern times, but he is not really talking about going much beyond current administration policy, writes Daniel Drezner, a professor of international politics at the Fletcher School at Tufts University in Medford, Mass.

“It’s almost as if Cruz is just trying to occupy the GOP foreign policy sweetspot between Rubio and Paul rather than articulating a coherent doctrine,” Professor Drezner writes in a Washington Post piece.