A contested GOP convention? History offers some unusual clues

The prospect of a contested Republican convention has sparked speculation and controversy. But it's a not-uncommon part of the political process, and past conventions have not rubber-stamped voters' choices.

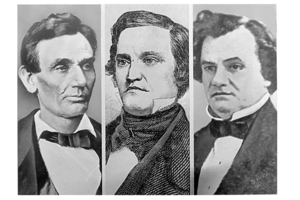

Abraham Lincoln (l.) lacked a plurality of delegates at first, but ended up winning the 1860 Republican nomination on the third ballot. That set up a general election race against John C. Breckinridge (c.) and Stephen Douglas (r.), representing Southern and Northern wings of the Democratic party.

Alexander Hesler/AP/File

Washington

The Republican candidate was certain his party’s national convention would nominate him for president. So were his many committed and vociferous supporters. Hadn’t he won the most delegate votes? Wasn’t he the most famous of all the contenders for the political crown?

But Republican insiders were worried about the candidate’s electability. His positions on major issues – including race and immigration – were out of step with major swing states. Down-ballot candidates didn’t want to lose due to a weak ticket leader.

The result was a hotly contested convention. On the first two ballots, no candidate received a majority of delegate votes. Then on the third, the contest dramatically ended, as support shifted to a dark horse candidate – someone who studied and prepared for just such a convention struggle.

Abraham Lincoln.

Yes, the Republican Convention of 1860 isn’t an exact analogy for the present day. Defeated front-runner William Seward was no Donald Trump. He was a sitting senator from New York and a giant of the then-young party. His views on race and immigration were too radical for some Republicans.

But the anecdote shows that brokered, or contested, or divided conventions have a long and colorful history in American politics. They’ve occurred periodically into the modern era. Both Democratic and Republican conventions were last truly contested in 1952.

Nor have they resulted in certain defeat due to a split party. Lincoln – well, no more need be said. And in 1952 Gen. Dwight Eisenhower won the presidency after defeating conservative favorite Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio at a bitter GOP Chicago convention.

“Six of the GOP’s ten brokered conventions have produced a nominee who went on to become president, with five of them winning the popular vote,” writes Trey Mayfield at the conservative website The Federalist.

The Republican National Convention of 2016 in Cleveland may not be a new chapter in this rich history. Donald Trump may well win the 1,237 delegates needed for nomination before primary season.

To do so he will need to maintain his voter support at his current percentage, and win key states, particularly California. California awards 172 Republican delegates and could well put Trump over the top. It votes on June 7 – primary season’s last day.

But it is also quite possible Trump will fall short. (Neither Ted Cruz nor John Kasich have a realistic path to winning a delegate majority outright.) In that case the nomination fight would go into overtime, all the way to the convention.

Trump has made clear he believes he should win the nomination if he enters the convention with a plurality of delegates and a big lead over his rivals in numbers of votes and states won. Anything else would constitute “disenfranchising” his voters, he says.

If the party tried to block him “you’d have riots”, Trump said during a CNN interview March 16.

But anti-Trump forces say that a contested convention should be just that – contested. Since 1860 the party has required a majority of delegates to win the convention. If no nominee has a majority of delegates, delegates quickly become free agents, meaning they can vote for whichever candidate they please, not just the one that won their state.

Rules are rules in this case.

“If Trump doesn’t get the delegates and doesn’t win at the convention no one would be TAKING anything from him. That would be ‘losing’,” tweeted Politico chief economic correspondent Ben White on March 16.

Let’s look back at 1952 to see how this worked. Back then Dwight Eisenhower was a political neophyte. Like Trump, he’d never been elected to political office. Unlike Trump, he had contributed greatly to the winning of World War II.

Ike didn’t know much about how the GOP’s rules worked. At the Chicago convention, his advisors were shocked to discover that he had no idea presidential candidates got to pick their running mates. He thought the delegates chose vice presidential nominees.

He figured things out pretty quickly. Eisenhower entered the convention in a close race with Senator Taft, a respected party elder making his third try for the office once held by his father, William Howard Taft. At the end of the first ballot, Ike led by 595 votes to 500. He needed only nine votes to reach 604, and a majority.

But the first ballot had a second act. Minnesota had voted for a favorite son candidate, former Gov. Harold Stassen. (Favorite sons were essentially placeholders, popular local or regional figures expected to eventually broker their state’s votes.) Before voting was closed, Stassen stepped up and changed Minnesota’s votes to “Eisenhower.” In that moment, Ike won.

He knew that despite this victory the convention remained deeply divided and that he needed to close that breach and unite the party if the Republicans were to have any chance of ending the Democrats’ 20-year hold on the White House.

“To that end, General Eisenhower’s first act, after he knew he had won, was to call on Senator Taft to ask – and receive – from him assurances that the Ohioan would campaign actively for the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket,” wrote The New York Times in its convention dispatch.

Historically, the role of US political conventions has been to choose the presidential contender who best represents the party.

In cases where there is a clear majority winner, that’s easy – they ratify the voters’ choice. But if the vote is split among a number of contenders the question of who has the most delegates becomes subordinate to the “best represents” question, writes The Federalist’s Mayfield.

The Republican Party has had 10 conventions where no candidate had a majority of delegates prior to the first ballot. In seven of those, the candidate who entered the convention with a plurality, or the most delegates, lost.

Gambling magnate Trump thus might face long odds in a contested convention, historically speaking.

Of course, Trump and his advisers may not be much worried. If he’s demonstrated anything this primary season it is that he is masterful at rousing his supporters. And history, he might point out, is yesterday, by definition. A very long time ago. Who cares about the convention of 1952, much less that of 1860?

The nation’s cultural and political context is much different today. Post-Watergate reforms have opened up the whole nominee-choosing process. It’s much more about the people’s choice, and less about backroom deals.

The vast majority of US elections are decided by the simple question of who got the most votes. No fancy ranked-choice voting here, where voters list a number of candidates in order of preference. That’s for loser countries like Australia. Sad!

That’s how Trump might put it, anyway. US voters just aren’t used to contested conventions anymore and might see them as odd and undemocratic.

“Perhaps the most powerful force working against the stop-Trump movement is the widely-accepted norm of democratic legitimacy awarded to the leading candidate in an electoral competition. Even the recipient of a mere plurality can claim to be the people’s choice, at least in comparison to any other single individual, and Trump, as a near-certainty to place first in the delegate count, will surely do so with no little vehemence,” writes Boston College political scientist David A. Hopkins on his "Honest Graft" blog.