Who coined the name 'United States of America'? Mystery gets new twist.

Historians continue to debate who came up with the formulation 'United States of America' as the name for the new nation. A new discovery could shift the discussion.

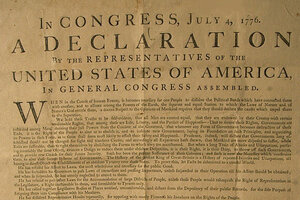

Was the Declaration of Independence (a rare first printing of which is shown here) the first mention of the 'United States of America'? Maybe not.

Elise Amendola/AP/File

It may seem surprising, but nobody is really sure who came up with the phrase, “United States of America.”

Speculation generally swirls around a familiar cast of characters – the two Toms (Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson), Alexander Hamilton, Ben Franklin, and even a gentleman named Oliver Ellsworth (a delegate from the Constitutional Convention of 1787). But every instance of those gentlemen using the name "United States of America" is predated by a recently discovered example of the phrase in the Revolutionary-era Virginia Gazette.

So who was perhaps the first person ever to write the words "United States of America"?

A PLANTER.

That was how the author of an essay in the Gazette signed the anonymous letter. During that time, it was common practice for essays and polemics to be published anonymously in an attempt to avoid future charges of treason – only later has history identified some of these authors.

The discovery adds a new twist – as well as the mystery of the Planter's identity – to the search for the origin of a national name that has now become iconic.

Several references mistakenly credit Paine with formulating the name in January 1776. Paine’s popular and persuasive book, "Common Sense," uses “United Colonies,” “American states,” and “FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES OF AMERICA,” but he never uses the final form.

The National Archives, meanwhile, cite the first known use of the “formal term United States of America” as being the Declaration of Independence, which would recognize Jefferson as the originator. Written in June 1776, Jefferson’s “original Rough draught” placed the new name at the head of the business – “A Declaration by the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in General Congress assembled."

Jefferson clearly had an idea as to what would sound good by presenting the national moniker in capitalized letters. But in the final edit, the line was changed to read, “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” The fact that “United States of America” appears in both versions of the Declaration may have been enough evidence to credit Jefferson with coining the phrase, but there is another example published three months earlier.

Beginning in March 1776, a series of anonymously written articles began appearing in The Virginia Gazette – one of three different Virginia Gazettes being published in Williamsburg at that time. Addressed to the “Inhabitants of Virginia,” the essays present an economic set of arguments promoting independence versus reconciliation with Great Britain. The author estimates total Colonial losses at $24 million and laments the possibility of truce without full reparation – and then voices for the first time what would become the name of our nation.

“What a prodigious sum for the united states of America to give up for the sake of a peace, that, very probably, itself would be one of the greatest misfortunes!” – A PLANTER

So who is A PLANTER?

Likely candidates could be well-known Virginians, like Richard Henry Lee, Patrick Henry, or even Jefferson. Some of the essay’s phrasing can be found in the writings of Jefferson. For example, “to bind us by their laws in all cases whatsoever,” appears in both the essay and Jefferson’s autobiography.

A Planter could be the nomme de plume of an intrepid New Englander, like John Adams, attempting to rally support for independence in the South, a similar motive for why he charged Jefferson, a Southerner, to pen the Declaration.

A Planter could be Benjamin Franklin, who was well-known for his hoaxes and journalistic sleight-of-hand. Or maybe, A Planter is exactly whom the letters portray, an industrious, logistics-minded landowner, evangelizing about the promise of increased prosperity should the “united states of America” ever become an independent nation.

There is a possibility the author was aware of the historical significance of introducing the new name for the first time, as he or she observes:

“Many to whom this language is new, may, at first, be startled at the name of an independent Republick, [and think that] the expenses of maintaining a long and important war will exceed the disadvantages of submitting to some partial and mutilated accommodation. But let these persons point out to you any other alternative than independence or submission. For it is impossible for us to make any other concessions without yielding to the whole of their demands.”

So, the mystery continues.

Our anonymous author, A Planter, certainly did plant a few seeds in the spring of 1776. Those seeds came to fruition as the first documentary evidence of the phrase “United States of America” – an experiment in self-government that quickly became one of the most powerful and influential nations in the world.