Presbyterian church rejects same-sex marriage

The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) has rejected a bid to redefine marriage as 'a covenant between two people,' voting instead to conduct a two-year study of the divisive issue.

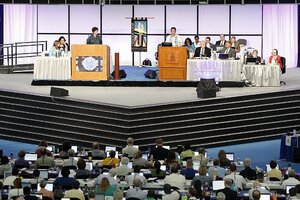

Rev. Neal Presa, at podium on right, serves as moderator during a session of the 220th General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) on Thursday, July 5, 2012, in Pittsburgh.

Keith Srakocic/AP

Presbyterians debated for more than three hours Friday whether to change their definition of marriage. In the end, they preserved the traditional meaning, upheld a ban on officiating gay weddings, and sustained related tensions that have roiled their denomination for years.

With a 52-percent majority, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) shot down a bid at its Pittsburgh meeting to redefine marriage in the church constitution as “a covenant between two people.” As a result, marriage is still defined there as “a civil contract between a woman and a man.”

The vote means Presbyterian clergy who officiate at gay weddings, even in states and other jurisdictions that recognize same-sex marriages, violate protocol and risk censure. Later Friday night, the Assembly voted to convene a two-year, churchwide study on the theology of marriage.

IN PICTURES: The gay marriage debate

Participants on both sides said the denomination had delayed the “inevitable.”

“It was rather surprising,” said Mateen Elass, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Edmond, Okla. and an opponent of redefining marriage. “It’s inevitable that at some point our General Assembly will vote in favor of redefining marriage. This decision has just given some respite to the denomination before it faces an onslaught of departures.”

Distraught by the narrow defeat, proponents of redefining marriage hugged and consoled one another. They said the church missed an opportunity to be prophetic and would eventually come around.

“The move to affirm long-term, committed, same-sex relationships … as blessings from God is both the right way to go in the long-run, and inevitable,” Rick Ufford-Chase, a former moderator of the General Assembly, said in an email. “There are more and more people, of all ages, who are changing their minds about this important matter.”

The PCUSA, like other mainline denominations, has felt the sting of grappling with sexuality issues for decades. Last year, a new rule took effect allowing non-celibate, gay PCUSA clergy to serve openly. Church court cases and tense votes every two years have frayed nerves as believers, bound by a shared faith yet torn on an emotional issue, struggle to hang together as a spiritual community.

“Lord of all graces … we don’t know what to do,” prayed General Assembly Moderator Neal Presa. “We keep voting and talking and listening. And yet we find ourselves divided.”

Prospects of a conservative exodus loomed large as attendees considered the proposal. Hunter Farrell, the PCUSA’s director of world mission, warned that an estimated 18 international partners would sever ties with the denomination if it redefined marriage.

Redefining marriage “would create too much division,” said Timothy Devine, co-pastor of First Presbyterian Church of Endicott, NY, during the debate. “I co-pastor a house of worship where 60 percent of the membership is waiting to see what the [General Assembly] will say as it looks at the understanding of marriage.”

As the vote approached, participants paused several times an hour to seek higher wisdom. They prayed aloud and silently, quoted scripture, sang hymns, and talked spontaneously in small groups about “what you’re hearing and what you’re feeling.”

By late afternoon, proponents of redefining marriage seemed to gain momentum. Floor votes defeated two proposals that conservatives had championed in bids to derail the marriage redefinition effort. The assembly appeared to be on the verge of recommending an historic change, one that would need to be ratified by two-thirds of the church’s presbyteries before it could take effect.

But any real or perceived momentum vanished as the final tally was announced. The room was quiet, notably devoid of celebration.

“Traditionalists and evangelicals were kind of stunned that the vote came out the way it did,” Elass said. “They were muted in their response, partly out of respect [for their disappointed brethren], but mostly out of tiredness.”