Why Cosby accusers are being listened to this time

Several women have come forward in recent days to publicly accuse Bill Cosby of sexual assault. The fact that people are listening could point to a shift in society.

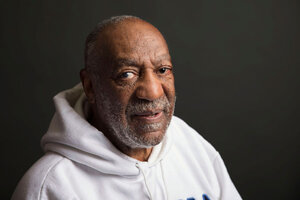

Actor-comedian Bill Cosby poses for a portrait in New York in this file photo. NBC announced Wednesday that it has canceled plans for a family comedy starring Bill Cosby.

Victoria Will/Invision/AP/File

The public dialogue around Bill Cosby and the allegations of sexual assault against him points to a shift in how society views both sexual violence and the women who come forward with their stories, a number of experts say.

Allegations against Mr. Cosby have existed for years and have received comparatively little attention. But since comedian Hannibal Buress touched on the issue in October, it has gained traction, with new women publicly accusing Cosby.

On Tuesday, Netflix announced that it was postponing a comedy special starring Cosby. And NBC has halted development of a Cosby sitcom, Entertainment Weekly reports.

The strong reaction “is going to become an important chapter in the whole story of violence against women,” says Robert Thompson, a professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University.

Women accusing men of sexual crimes – and particularly women accusing prominent men – have long had to fight public prejudice in favor of the accused. The events of recent days suggest that equation is beginning to change.

The fact that the Cosby allegations are being largely received as credible signifies progress toward “a greater understanding from the public about the nature of [sexual assault] crimes and their willingness to believe victims when they come forward,” says Scott Berkowitz, founder and president of the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN).

In the age of viral social media, there is some concern that the pendulum may swing too far in the other direction, with the accused becoming prematurely convicted in the court of public opinion.

Cosby’s attorney called the most recent allegation – by model Janice Dickinson Tuesday – “a defamatory fabrication” in a letter to TheWrap, a Hollywood news site.

But like the Ray Rice video, which pointed to an increasingly zero-tolerance attitude toward domestic violence in society, the Cosby sexual assault allegations are “opening a dialogue,” says Gemma Puglisi, a professor of public communication at American University.

The allegations are “devastating” and “Mr. Cosby has the right to provide his side of the story,” Ms. Puglisi says. But for the women coming forward, “it’s important that their voices are being heard and they now have a platform to talk about it.”

On Tuesday, Ms. Dickinson told “Entertainment Tonight” that she was sexually assaulted after being given wine and a pill by Cosby in 1982, while visiting him at Lake Tahoe to discuss a potential job.

On Monday, former publicist Joan Tarshis told “ET” that she had been assaulted twice by Cosby in 1969. On Friday, Barbara Bowman published an online Washington Post story detailing her allegations of being drugged and raped by the comedian when she was a 17-year-old aspiring actress in 1985.

None of the alleged incidents led to criminal charges. In 2006, Cosby settled a civil lawsuit by Andrea Constand, who had alleged sexual assault by Cosby in 2004.

Many people don’t report sexual assault to the police, and when the alleged perpetrator is a high-profile person, “that presents an additional barrier,” says Tracy Cox, a spokeswoman for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. “We often call this a silent crime because people who perpetuate sexual violence often use coercion or threats to victims to keep them silent,” she says.

But in recent days, the “phenomenon of safety in numbers” has come into play, says Mr. Berkowitz of RAINN, noting that the same dynamic was seen in the series of accusations that came out against priests in Catholic churches and against Penn State assistant coach Jerry Sandusky.

The women accusing Cosby have implied that one reason to go on record is to encourage others to feel comfortable reporting sexual assault.

Dickinson alleged that she wanted to tell the story as part of her 2002 autobiography, but that Cosby and his lawyers pressured her and her publisher to remove it – a point Mr. Singer specifically denied in his letter to TheWrap.

In her piece in the Washington Post (which is not the first time she’s told the story publicly), Ms. Bowman explained why she didn’t go to police:

It “was so horrifying that I had trouble admitting it to myself, let alone to others. But I first told my agent, who did nothing.… A girlfriend took me to a lawyer, but he accused me of making the story up. Their dismissive responses crushed any hope I had of getting help; I was convinced no one would listen to me. That feeling of futility is what ultimately kept me from going to the police.”

Bowman and the other accusers join a growing movement of women who hope their stand will help take away the stigma for victims, reduce the dismissals and blame victims sometimes face, and improve the justice system.

Each victim responds to the trauma of sexual assault differently, says Ms. Cox of the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. “The fact that they don’t talk about it immediately … often that’s the case; it can be weeks, months, years,” before they are ready.

Berkowitz of RAINN adds: “The point we’d like to get to is where victims are coming forward immediately after the attack and choose to report to the police because they think they will get a fair investigation.”

Amid this positive shift toward taking accusers’ stories seriously, it’s also important for society to maintain some desire to scrutinize the veracity of accusations, which can seriously damage someone’s career, cautions Professor Thompson of Syracuse.

Whether Cosby opts to challenge any of the women’s stories in court remains to be seen. In a defamation case, “it would be Cosby’s burden to show that it was false,” says David Schulz, a lawyer with the New York firm Levine, Sullivan Koch & Schulz, which handles news and entertainment defamation claims.