As South Carolina mulls furling flag, pro-Confederate protests grow

To some on the pro-Confederate side, the flag is a symbol of the South, depicting valor and also representing opposition to political tyranny. But South Carolina may have the votes to remove the flag from State House grounds.

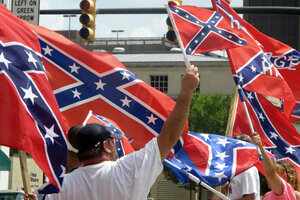

Supporters of keeping the Confederate battle flag flying at a Confederate monument at the South Carolina Statehouse wave flags during a rally in front of the statehouse in Columbia, S.C., on Saturday, June 27, 2015. Gov. Nikki Haley and a number of other state leaders have called for the removal of the flag following the recent shooting deaths of nine black parishioners in a church in Charleston.

AP Photo/Bruce Smith/File

Atlanta

South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who has called for lawmakers to remove the Confederate battle flag from the grounds of the State House, appears to have the votes to make that happen, according to an assessment by the Associated Press and other media outlets.

Long hailed as a genteel reminder of the “lost” South, the Confederate battle flag has taken on a darker meaning, especially in light of the shootings in Charleston, S.C. Authorities say Dylann Roof killed nine black parishioners at a church there after burning an American flag and posing with a Confederate one.

But even though South Carolina’s Republican governor and others now say it’s time to permanently furl what for many has become an embodiment of segregation and white supremacy, not all Southerners are on board. To some on the pro-Confederate side, the flag is a symbol of the South, depicting valor and also representing opposition to political tyranny. And the push to take it down inflames an already-wounded sense of Southern pride.

In recent days, those holding such views have made their presence known:

• Hundreds of Southern heritage proponents celebrated the Southern Cross design in Montgomery, Ala., last weekend.

• After federal officials stopped selling the Confederate battle flag at Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park, protesters on Saturday waved flags around nearby Fort Oglethorpe, Ga.

• On Sunday in Dalton, Ga., nearly 150 trucks converged for an impromptu parade, each flying a Confederate flag.

• On Monday night, flag protesters fist-clashed with flag supporters at the site of the Confederate flag on the State House grounds in Columbia, S.C. One bloodied neo-Confederate told a reporter that an effort to remove the embattled rebel flag “will make me walk taller.”

Indeed, those standing by the battle flag don’t see it the way others do. The resulting protests and counterprotests suggest that an era of “de-Confederatization” could be pocked with unrest, historians say.

But at the same time, the renewed debate over the flag may be pointing up the limits of the pro-Confederate side.

“I think that the movement [on the flag] has caught the neo-Confederates by surprise, and it’s shown how their strength was fragile, and we didn’t realize how fragile it was,” says James Loewen, an emeritus professor of history at the University of Vermont and co-editor of “The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader.”

“The fact is, more than 150 years after the Confederacy came to an end, the [protests are showing how the] reign of the neo-Confederates is also coming to an end,” Mr. Loewen says.

The flag, and Southern symbols more generally, are a complicated stamp on the modern South. One issue that political leaders have been dealing with in recent days is how difficult it is to distinguish some of the flag’s historical aspects from its use as a cudgel for white supremacy.

Many older Southerners see the flag as a statement of Southern distinctiveness that epitomizes uniquely American virtues of liberty and self-reliance. For young Southerners, it is an icon of youthful rebellion and anti-establishment attitudes. And in a pluralistic South, the idea that it somehow hails white supremacy seems, to some, anachronistic.

“All of this is in the eye of the beholder, because you can look at any symbol like that and it means different things to different people,” says Michael Hill, president of the secessionist League of the South. “Southerners, I think, have come to the realization that they’re not going to let outsiders ... define an honorable symbol that stands more than anything else for the sacrifices of soldiers 150 years ago.”

Mr. Hill adds, “It’s a symbol against tyranny, it’s the internationally recognized symbol of the South, it’s a Christian symbol. It’s a solemn banner.”

To be sure, the removal of Confederate symbols has continued after states like Georgia and South Carolina struggled in the late 1990s and early 2000s with how to reconcile the flag’s heritage with its modern connotations. In 2000, South Carolina removed it from the capitol dome to a soldier’s memorial on State House grounds, in what many thought was a final act of compromise.

Support in South Carolina for the flag on those grounds has historically hovered around 50 percent. But polls now suggest that a majority of Americans, including South Carolinians, acknowledge that the same flag that depicts valor to some is a hateful reminder of Southern state governments raising the flag in protest of civil rights moves in the 1950s and ’60s.

Given the recent, widespread condemnation of the flag even from traditional allies on the political right, “it looked like only one side was playing, like a football game where only one team had come out of the dressing room,” says Hill of the League of the South.

But he vows that the pro-Confederate side will come out, too.

“The real fact of the matter is, the Southern people, this sleeping giant, they’re going to take some time to mobilize, but make no mistake: They’re mobilizing right now,” Hill says.

On July 19, a North Carolina chapter of the Ku Klux Klan will hold a rally at the State House memorial in South Carolina. In a statement, the Loyal White Knights referred to Mr. Roof, the accused Charleston shooter, as a “warrior.”

After the brief fist-clash in Columbia on Monday night, pro-Confederate flag protester Joe Linder relayed his resolve to CBS News: “The blood on my face, the blood in my teeth, the blood on my hands is no comparison to the Southern blood that runs through my veins.”

According to Hill, companies like Ruffin Flag sold 22,000 Confederate flags in one day last week, compared with the 150 they usually sell per day. Also, three Chinese flag-makers are solely producing Confederate flags to satisfy demand, he says.

Still, despite the bloody noses in Columbia on Monday night, the pro-flag movement is largely symbolic – and the push from others to take the banner down won’t solve everything.

Removing the flag “is not the end of racism in America; this is not the end of white supremacy,” says Loewen, the emeritus professor. “Nevertheless, this is very important.”