Can alt-weeklies write a future for themselves in a digital era?

Just last week, Nashville's The Scene shuttered. In 2017, the Baltimore City paper folded, the LA Weekly cut most of its editorial staff, and the Village Voice axed print. But supporters say the need remains for vigilant reporters intensely focused on local news.

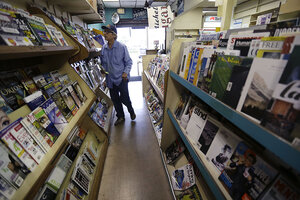

In a sign of the digital times, one of the last newsstands in metro New Orleans closed in 2015. The owners say the newsstand has been losing money because people aren't buying as many newspapers and magazines. The country's alt-weekly newspapers' fortunes also have faded along with newsstands over the previous decade.

Gerald Herbert/AP

Washington

In a news landscape filled with layoffs and closings, the alt-weekly may be perhaps the most precarious form of journalism.

Lisa Snowden-McCray has started one anyway.

And, bucking conventional wisdom about digital platforms, it’s in print. But then, bucking convention has always been part of the alt-weekly ethos.

The veteran journalist launched the Baltimore Beat after her old newsroom, the Baltimore City Paper, shuttered operations in November after 40 years.

While the business model for alt-weeklies – the scrappy, unapologetic siblings to more staid print journalism – may be unclear, the need for vigilant reporters intensely focused on local news and political leaders is not, Ms. Snowden-McCray and other alt-weekly supporters say.

“We help push the conversation forward,” says Snowden-McCray.

It's been a rough time for the country’s remaining alt-weeklies. Besides the demise of the Baltimore City paper, the LA Weekly cut 9 of its 13 editorial staff, and the storied Village Voice moved exclusively online. Just last week, Nashville's The Scene shuttered. The staff of the Washington City Paper were facing salary cuts of 40 percent, until a last-minute rescue by venture capitalist Mark Ein.

“Every thriving community needs strong local news, and Washington City Paper has been a critical part of the fabric of our city, and a great incubator of journalistic talent, for decades,” Mr. Ein said in a statement in December.

Sweeping changes in the media landscape over the past decade have hit alt-weeklies, along with small-town newspapers and other forms of community journalism, especially hard. Bloggers, social media, and the rise of online niche publications have led to the collapse of the financial model that allowed alt-weeklies to flourish. The Association for Alternative Newsmedia had 135 members in 2009. Nine years later, that number has fallen to 110. The top 20 alt-weeklies lost 11 percent of their subscribers in both 2014 and 2015, according to the Pew Research Center.

“In a moment when The New York Times has a special section called ‘Wealth’ (actual headline: ‘I’m Rich, and That Makes Me Anxious’) alt-weeklies remain the official papers of the vulnerable, invisible, and underserved,” wrote Philip Eil in the Columbia Journalism Review on Jan. 25. “They’re an extra set of eyes on legislators, local officials, and law enforcement. They’re often the ombudsman for the local media, monitoring daily newspapers and airwaves the same way government environmental agencies track water and air quality. And, in many cases, they’re an all-too-rare source of original investigative – or, at least, in-depth – reporting on a range of topics.”

Rising from the counterculture movement of the 1970s, alt-weeklies created a space for young reporters who chafed at the strictures of traditional journalism. Profanity, liberal politics, and discussions on local bands filled the pages. As an alternative source of news, alt-weeklies believed it was their duty to provide information that detailed the happenings in their communities. The papers have been the training ground for some of today’s leading journalists and writers, including CNN’s Jake Tapper, MSNBC host Chris Hayes, and authors such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Katherine Boo, and Susan Orlean.

The alt-weekly provided “deep coverage on an almost neighborhood level,” says Dan Kennedy, an associate professor of journalism at Northeastern University in Boston and a former media columnist at the now-defunct Boston Phoenix. They were “digging in much more than The Washington Post can do on a daily basis.”

Without the size and budget of the large dailies, alt-weekly newsrooms make up for the lack of staff with determination and obsessiveness. For example, The Willamette Week in Oregon famously went through elected officials’ trash, after Portland law enforcement determined they had a right to search residents’ trash without a warrant.

Tim Keck, founder and publisher of the Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger, describes an “all hands on deck” mentality – whether it’s having book editors jumping into real-time election coverage or huddling at a staff member’s house to cover a nearby manhunt.

As alt-weekly newsrooms continue to shrink, their tradition of long form, on-the-ground reporting has become increasingly difficult and expensive.

Alt-weeklies have typically been slower to adopt new business models, according to Mr. Keck. But for his part, he does believe that there is opportunity to continue producing solid journalism and have a profitable online revenue stream. Some publications have considered paywalls to help generate capital, while others have decided to go down the nonprofit route and cut out the print product to cut costs.

“The landscape is ever-changing, and my view is that unless you are entrenched with a very strong digital platform and a full digital agency service it will be a tough road ahead,” says Scott Tobias, CEO of the Voice Media Group.

The Baltimore Beat has two reporters, in addition to Snowden-McCray. She occasionally helps deliver the paper, and personally identifies neighborhoods that still crave hyper-local news in a city that has captured the national spotlight, from stories on police brutality and poverty to other social justice issues.

When it comes to the best way to serve underserved neighborhoods, she says there is no substitute for print.

“A lot of people don’t have the luxury of having a smart phone,” Snowden-McCray says. “We should strive to continue to have a paper in hand.”