College football players call for a union – and a seat at the NCAA table

College athletes, putting in a 40-hour work week with no pay, say they're not amateurs. With coaches and commissioners making millions, they want a College Athletes Players Association.

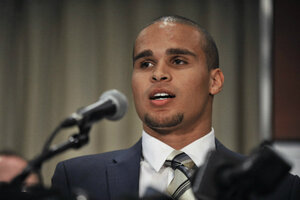

Northwestern quarterback Kain Coulter speaks during a news conference in Chicago on Tuesday. Calling the NCAA a 'dictatorship,' a handful of Northwestern football players announced Tuesday they are forming the first labor union for college athletes, the College Athletes Players Association.

Paul Beaty/AP

A bid by Northwestern University football players to unionize faces significant legal barriers, but even the specter of a union could help tip the highly commercialized playing field more in student-athletes’ favor.

“My goal is to make sure that all student athletes are set up for success long after their playing days are over,” said Northwestern quarterback Kain Colter at a press conference Tuesday in Chicago, where he outlined plans to form the College Athletes Players Association.

Among the issues driving a move to unionize college athletes are low graduation rates among players and the absence of protections for student athletes who face injury-related medical issues long-term, he said.

Northwestern was not mistreating its players, Mr. Colter added, but simply playing by the rules of the game as they currently stand. “We need to eliminate unjust NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association] rules that create physical, academic, and financial hardships for college athletes across the nation,” he said.

A majority of Northwestern football players signed cards to file a petition with the National Labor Relations Board, Colter said. The NLRB is expected to conduct a hearing within about 10 days.

The NCAA was quick to point out that there’s no precedent for this type of union: “Many student athletes are provided scholarships and many other benefits for their participation…. Student-athletes are not employees within any definition of the National Labor Relations Act or the Fair Labor Standards Act,” said NCAA chief legal officer Donald Remy, in a statement.

If the NLRB does recognize the group as a collective bargaining unit, “it will be pretty significant,” says Andrew Zimbalist, an economics professor at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. But the impact would be “primarily in the momentum and publicity it garners,” he says. The NCAA or some other outside body, such as Congress, could feel the pressure to bring about the kinds of changes the players are looking for, he adds.

On the other hand, a successful effort to unionize at Northwestern could also throw a monkey wrench into the whole system of competitive college football, creating a patchwork of teams that aren’t competing under the same terms, says Michael LeRoy, an expert on collective bargaining in athletics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

That’s because private universities are governed by the National Labor Relations Act, but public universities, home to many of the major college football teams, are governed by state laws that vary in whether they allow public employees to unionize.

Unions at some schools could therefore lead to more spending on players, thereby disrupting the parity that NCAA rules are designed to ensure, Professor LeRoy says. It could also lead to a scenario where a stadium is packed with fans and one of the two teams slated to play suddenly decides to go on strike.

The question of unionization plays into ongoing debates about whether players are being “properly compensated for what amounts to de facto employment,” LeRoy says. With players routinely putting in more than 40 hours a week for football-related activities, the term “student-athlete” becomes somewhat “paradoxical,” he adds.

“How can they call this amateur athletics when our jerseys are sold in stores and the money we generate turns coaches and commissioners into multimillionaires?” Colter asked at Tuesday’s press conference, while also noting that the point of unionizing would not be to ask for players to be paid outright. “The current model represents a dictatorship…. We just want a seat at the table,” he said.

The president of the College Athletes Players Association, former UCLA football player Ramogi Huma, said the union would help ensure that scholarships cover the full cost of tuition, and that medical coverage extends beyond the playing years, two goals shared by another organization he heads, the National College Players Association.

Mr. Huma described the union push as “the first domino,” and said efforts could move beyond private universities to public ones as well.

The United Steelworkers is supporting the college football players’ effort, including paying for legal expenses.

If approved, “the strategy the union pursues would be vitally important,” says Professor Zimbalist. One big question would be whether the NCAA would kick out a unionized team “for transgressing the strictures of amateurism,” he says. But if the union is simply asking for better health insurance benefits and cost-of-attendance stipends, it isn’t necessarily violating any of those rules.

While a union is probably a long way off, given the legal process involved, colleges and universities are very concerned about protecting players from injury, says Ada Meloy, general counsel for the American Council on Education, a higher education membership organization in Washington.

Jim Phillips, Northwestern’s vice president for athletics and recreation, said in statement that the university agreed with the NCAA that student-athletes are not employees, but added that “the health and academic issues being raised by our student-athletes and others are important ones that deserve further consideration.”

• Material from Associated Press was used in this report.