Big Brother: Can your school require your Facebook password?

A new anticyberbullying measure in Illinois now allows schools to have access to students’ social media profiles. A necessary step or a step too far?

New legislation in Illinois gives school and state officials access to students' social media accounts. School districts across the country are drafting and enacting similar laws in an effort to prevent cyberbullying and online harassment.

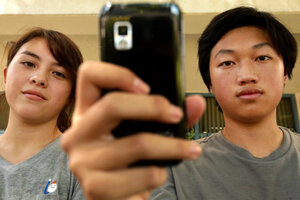

Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times/AP Photo

The conversations around data privacy and internet safety just got hotter.

A new Illinois state law can now compel students to hand over their social media login credentials to their school if school and state officials believe it can help prevent hostile online behavior – raising privacy concerns among parents and students alike.

The law, which then-Governor Pat Quinn signed in August and went into effect Jan. 1, is an effort to curb cyberbullying and online harassment both in and out of the classroom, before it gets out of hand. Previously, Illinois schools could intervene if online bullying occurred during class hours.

“Children need to understand that whether they bully a classmate in school or outside of school using digital devices, their actions have consequences,” State Rep. Laura Fine (D-Glenview) said in a statement. “Students should not be able to get away with intimidating fellow classmates outside of school.”

On the other hand, as Illinois mom Sara Bozarth told local Fox affiliate KTVI: “It’s one thing for me to take my child’s social media account and open it up, or for the teacher to look or even a child to pull up their social media account, but to have to hand over your password and personal information is not acceptable to me.”

The discussion in Illinois mirrors similar conversations about cyberbullying and data privacy in the United States, as cities and counties across the country struggle to find ways to protect children online.

In 2013, a school district in Los Angeles was met with suspicion and media scrutiny when it spent more than $40,000 to monitor the social media profiles of its students for any signs of bullying or self-harm, the Los Angeles Times reported. In Denver last year, the Colorado Defense Bar opposed the passage of a cyberbullying bill that criminalized using social media to cause “serious emotional distress on a minor.”

Lawmakers in Albany County, New York also had to pare down their original bill against cyberbullying after the state Supreme Court, citing First Amendment rights, struck it down in July. And a software program in Washington County, Maryland allows school officials to monitor students’ profiles for illegal and violent activity on and off campus, much to the chagrin of privacy advocates.

There’s no doubt that cyberbullying can get bad. While definitions vary, cyberbullying is at its core online harassment – any aggressive behavior, insults, denigration, impersonation, exclusion, and activities related to hacking against a person or persons – done repeatedly over a period of time, according to the Pew Research Center. Figures vary regarding the prevalence of cyberbullying among children and young adults, but most research estimates that anywhere between 6 to 30 percent of teens have experienced some form of it.

The worst consequences are death and self-harm, as in the 2013 case of 12-year-old Rebecca Ann Sedwick, who committed suicide after a group of middle-school students barraged her with text messages urging her to kill herself.

“Every student should feel safe from harassment, whether that’s in the school hallways or when using the internet or a cell phone,” former Gov. Quinn said after he signed the bill in Illinois. “In our technology-driven age, bullying can happen anywhere. This new law will help put an end to it.”

But others argue that there are ways to protect children besides monitoring and surveillance.

Jim Steyer, CEO of nonprofit Common Sense Media, told NPR in 2013 that his company tries to focus on informing and educating kids from a young age instead of watching their every move. The company developed a curriculum on “digital literacy and citizenship,” Steyer said, which teaches students how to use digital technology safely and responsibly.

"Our approach is teaching kids empathy," he said. "I think that's much better than spying on kids."